Lithic Materials

This site is proposed as a reference to characterize the known lithic materials of Mississippi. In addition to this site, the Surface Geology staff has published a map of the sources of lithic materials: 1:500000 Scale Native Lithic Materials Poster Size or Fact Sheet 3: Mississippi’s Native Lithic Material Sources Map. Discussions of anthropology are avoided except where absolutely necessary. Thus, it is important for the reader to understand this site does not indicate occurrences of lithic materials, only the sources of lithic materials that may occur anywhere in the state. Some of these materials may have been traded in from sources outside of Mississippi such as Arkansas Novaculite. It is the task of the archaeologist to identify the source of the lithic materials found on any site. Click the links below to see more information and photograph of a particular lithic material. Click on the photographs to view them in high resolution.

Detailed Summary

In archaeology, lithics are stone artifacts that have been purposefully modified, or worked, by human hands. In this science, where anthropological theory of the cultural past is pondered and debated largely on the examination of worked stone objects, an understanding of the presence and source of naturally occurring stones or native materials throughout the local geology is vital information when investigating indigenous archaeological sites. Natural availability and quality of geologic resources are not equally distributed. Therefore, understanding the source of these native lithic materials provides the archaeologist insight into the relationships of past cultures with each other, their available geological resources, and how these relationships may have evolved.

Quantifying the breadth of exotic trade of geologic material into this region throughout the thousands of years of the archaeological past would be an exhaustive study. Cultural boundaries undoubtedly changed much throughout history. For the sake of this webpage, the following characterizes natural lithic resources that exist within the artificial borders of the state of Mississippi.

Mississippi’s geology at the surface resides entirely in the Gulf Coastal Plain. This means that all the deposits found at the surface are sedimentary in origin. Mississippi is comprised of alternating layers of a variety of sand, silts, limestones, and clays that may only locally form into hard rock. Gravel deposits were brought by rivers that crossed the coastal plain, carrying with them chert along with a host of other rock types from distant bedrock regions.

Gravel deposits occur sporadically in geologic units which outcrop only in the northeast, western, and southern portions of Mississippi. Characterizing, describing, and differentiating gravel resources has been the focus of strategic geologic mapping efforts in recent years by the Mississippi Geological Survey. Previous literature by geologists once placed most outcrops of heavily oxidized, red sand and/or gravel-bearing deposits in Mississippi in the waste-basket term “Citronelle Formation.” This erroneous characterization was broadly applied for over a hundred years with disregard to the age, stratigraphic position, and even petrology of the deposits. Archaeologists furthered this misconception by confusing brown to honey-colored chert, “Citronelle Chert” as a chert type, regardless of the geologic province. Brown to honey-colored chert is ubiquitous to all of Mississippi’s chert-bearing gravel deposits. The “Citronelle Formation” is no longer recognized in Mississippi by the Mississippi Geological Survey. Outcrops once referred to as “Citronelle” have now been differentiated and properly attributed stratigraphically by geologic mapping. This work is being replicated by other state surveys where the “Citronelle Formation” had been previously mapped.

Varieties of chert and quartzite were the most utilized materials to produce knapped stone tools in Mississippi. This is due to their inherent mechanical property to propagate a predictable conchoidal fracture and their local availability as a geologic resource. Other geological resources were also modified and utilized in various ways according to their own suitability and physical properties.

Chert is microcrystalline to cryptocrystalline quartz that forms from the migration, concentration, and precipitation of silica. This primarily occurs as a diagenesis of limestone. This geochemical process results in silica crystallizing in the form of nodules or, in some cases, entire beds. Chalcedony is a term given to a more pure, often translucent, form of chert that forms from precipitation of silica-rich groundwaters. Though it can also form in limestones, it is often found in other lithologies as a void-filling mineral growth or replacement of fossils, such as in petrified wood.

Understanding sandstones, quartz, and quartzite can be quite confusing for both the collector and professionals alike. Sandstones are sedimentary rocks that can be made up of any sand-size particles. In Mississippi, most sandstones are made up of quartz grains. Sandstones can be cemented to various degrees of competence by a few different methods. Types of cement such as opal, chert, chalcedony, and quartz typically form the strongest bonds between the quartz grains. Iron-rich minerals can run the spectrum from weakly cemented limonite to much stronger bonded mineral cement such as siderite and goethite. Sandstones can also form by mineral re-growth of the individual quartz grains in the sand by filling neighboring pore space. The degree of cementation by this method also runs the spectrum due to the amount of pore space that is filled to interlock them.

The mechanical properties of sandstone are very important when describing lithic materials. Quartzite is a special term used for a sandstone that is cemented to such a high degree that it fractures preferentially across its sand grains. Whereas common sandstone preferentially breaks around the grains, disaggregating the stone. Because of this, quartzite can be knapped while sandstone cannot. This is an important distinction to make because all geologic resources in Mississippi that contain quartzite also contain sandstone and are utilized and processed differently based on their mechanical properties.

Quartzites can form in two different rock types, either sedimentary or metamorphic. Quartzites that formed as sandstones in sedimentary environments and were cemented by sedimentary processes are termed orthoquartzites while metaquartzites are sandstones that formed in sedimentary environments and were cemented by metamorphic processes. Because Mississippi’s geology at the surface is all sedimentary rock, quartzites in sandstone-bearing geologic formations are all classified as orthoquartzites. Quartzite constituents from gravel, however, can contain clasts of both metaquartzite and orthoquartzite depending on the bedrock from which they were derived. Some of Mississippi’s orthoquartzites are unstable over both time and environment, particularly those that rely on an abundance of opaline-silica as a cement. Artifacts made of an opaline-cemented quartzite can degrade, resulting in a once competently knapped artifact reducing back to a friable sandstone.

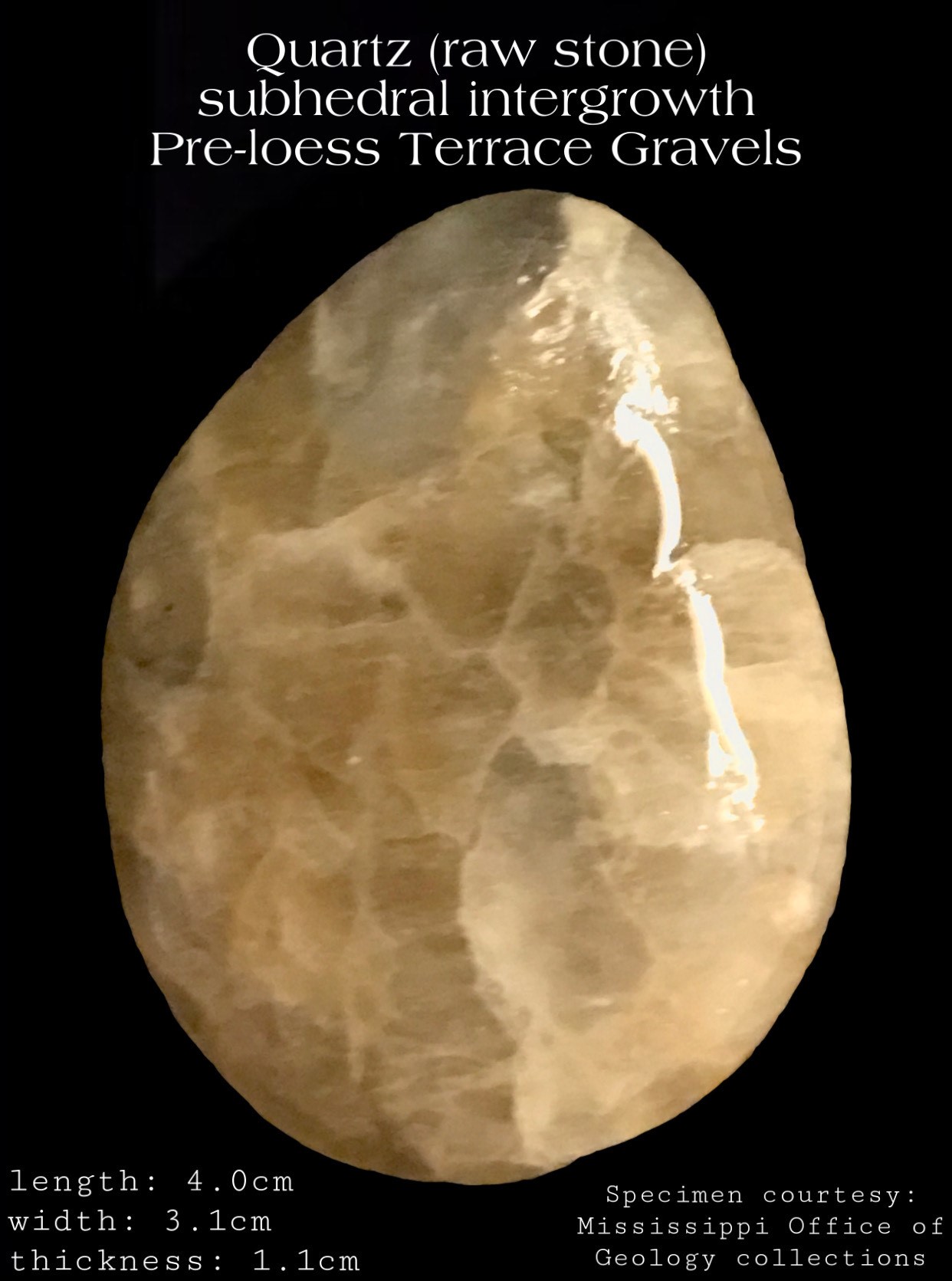

Quartz varieties are also a common constituent of all gravel resources in Mississippi. They are typically white-to-pinkish, translucent to even clear. Quartz gravel originates from a variety of igneous, metamorphic, or even other sedimentary bedrock sources. Varieties of crystalline quartz may also warrant clarity in differentiating from a quartzite when describing lithic materials in the archaeological record. Vein quartz, igneous quartz, and metamorphic quartz can often be misdiagnosed as quartzite because they commonly exhibit similar, grainy textures. This can be caused by crystals crowding one another and twinning during formation, like what is commonly exhibited in varieties of vein quartz. Metamorphic and igneous quartz sources can also exhibit grainy textures caused by extensive fracturing of quartz crystals.

Paleozoic Cherts

Chert-bearing limestones in Mississippi are only found in outcrops in the northeastern part of the state. Chert occurs in the limestones of the Fort Payne and the Tuscumbia Formations of Paleozoic age that outcrop in Tishomingo County. On the State Geologic Map of Mississippi from 1969, these limestones were grouped as the limestones, cherts, and shale of Meramec, Osage, and Kinderhook ages. This grouping was later replaced as the Fort Payne and Tuscumbia Formations by more recent geologic mapping. The Fort Payne Formation is the oldest of these two limestone units. The contact of the Fort Payne Formation is marked by beds of chert which can be seen along the banks of Pickwick Lake and the confluences of its tributaries. It is overlain by the Tuscumbia Formation. Though high-quality cherts are present in both formations, it is important to understand that diagenetic processes between two adjacent limestones do not recognize formational boundaries. Therefore, similar material may exist from either formation.

References: Tishomingo County Bulletin; Mississippi Paleozoic Rocks

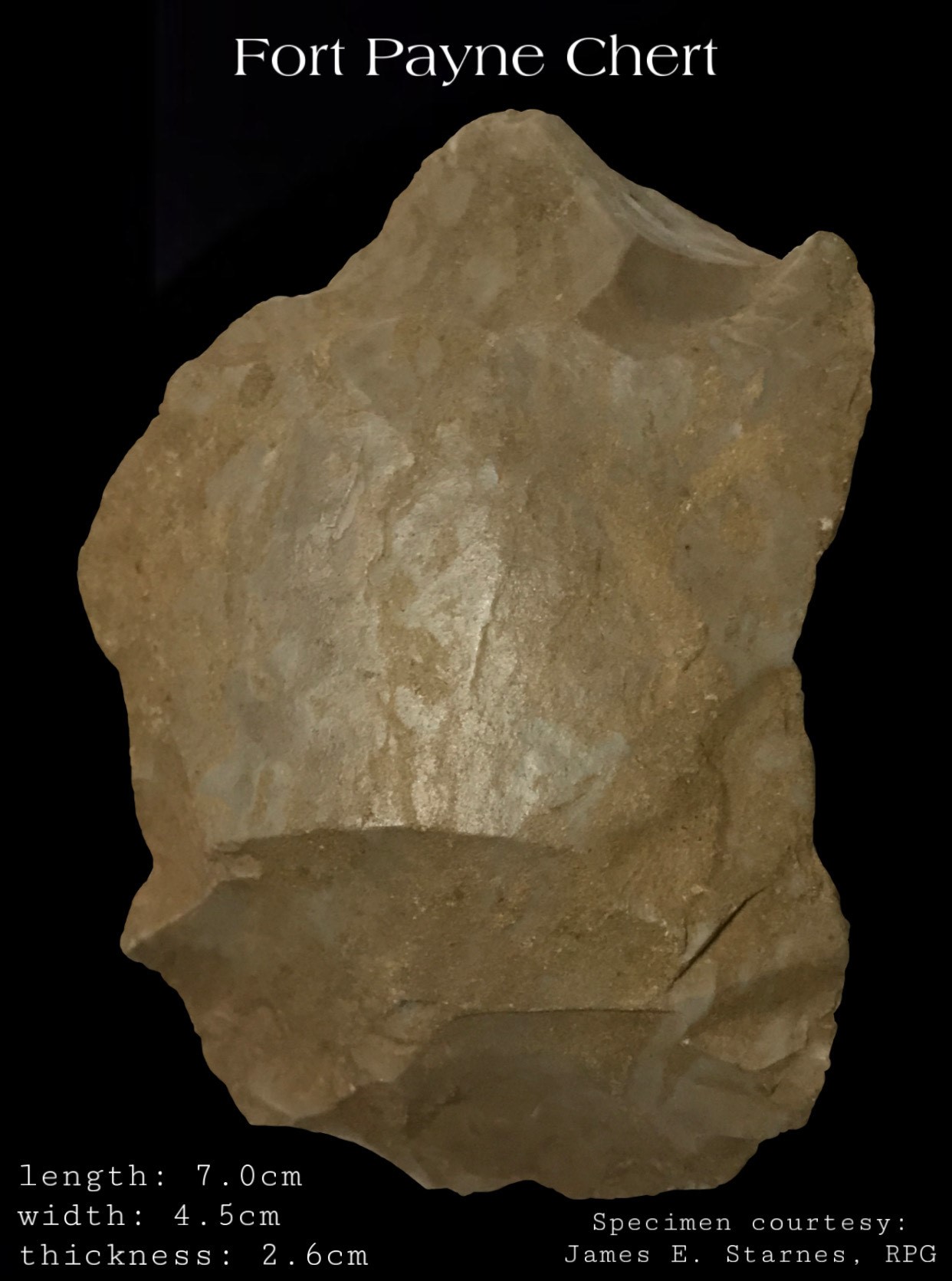

Fort Payne Chert

Chert that originates from the Fort Payne Formation is typically light-colored, ranging from a light tan-to-brown, light grey or white, and opaque. In many cases, it has a slightly grainy texture. Most often, it is distinguishable by light grey small blotches of vitreous, slightly translucent mottles. Heat-treatment alteration can change the color of the chert from its natural hue to light pink to red-brown and change the luster of the chert to moderately vitreous. A distinct blue-grey variety of Fort Payne chert outcrops outside of Mississippi. It is characterized as a dark bluish-grey chert with light blue, irregularly shaped patches.

Tuscumbia Chert

Knappable Tuscumbia Chert is black to blue-grey or brown, vitreous, and can exhibit low translucency or be opaque. Tuscumbia Chert most commonly occurs in nodular form. At outcrop, the chert nodule typically exhibits a chalky-textured tripolitic cortex. There usually is a zone of light brown chert immediately into the nodule from the cortex, surrounding the interior. Tuscumbia Chert may have feather-like intermittent banding resembling woodgrain. Tuscumbia Chert can be abundant in stream alluvium of drainages that dissect the formation. The chalky cortex is typically worn off in this reworked cobble form, leaving a milk chocolate brown smooth cortex. The blue-grey variety of Tuscumbia chert can be misidentified as Bangor Chert.

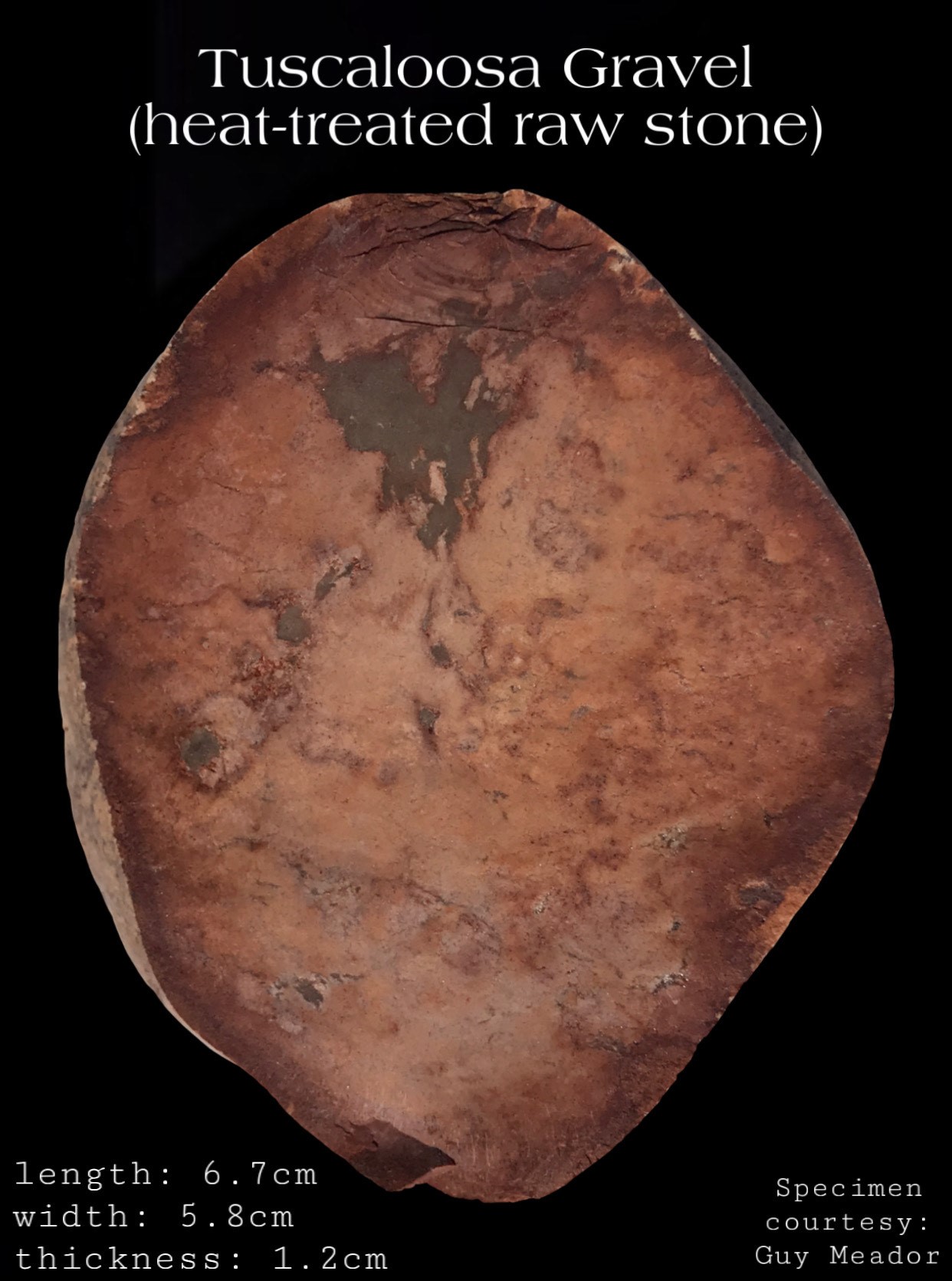

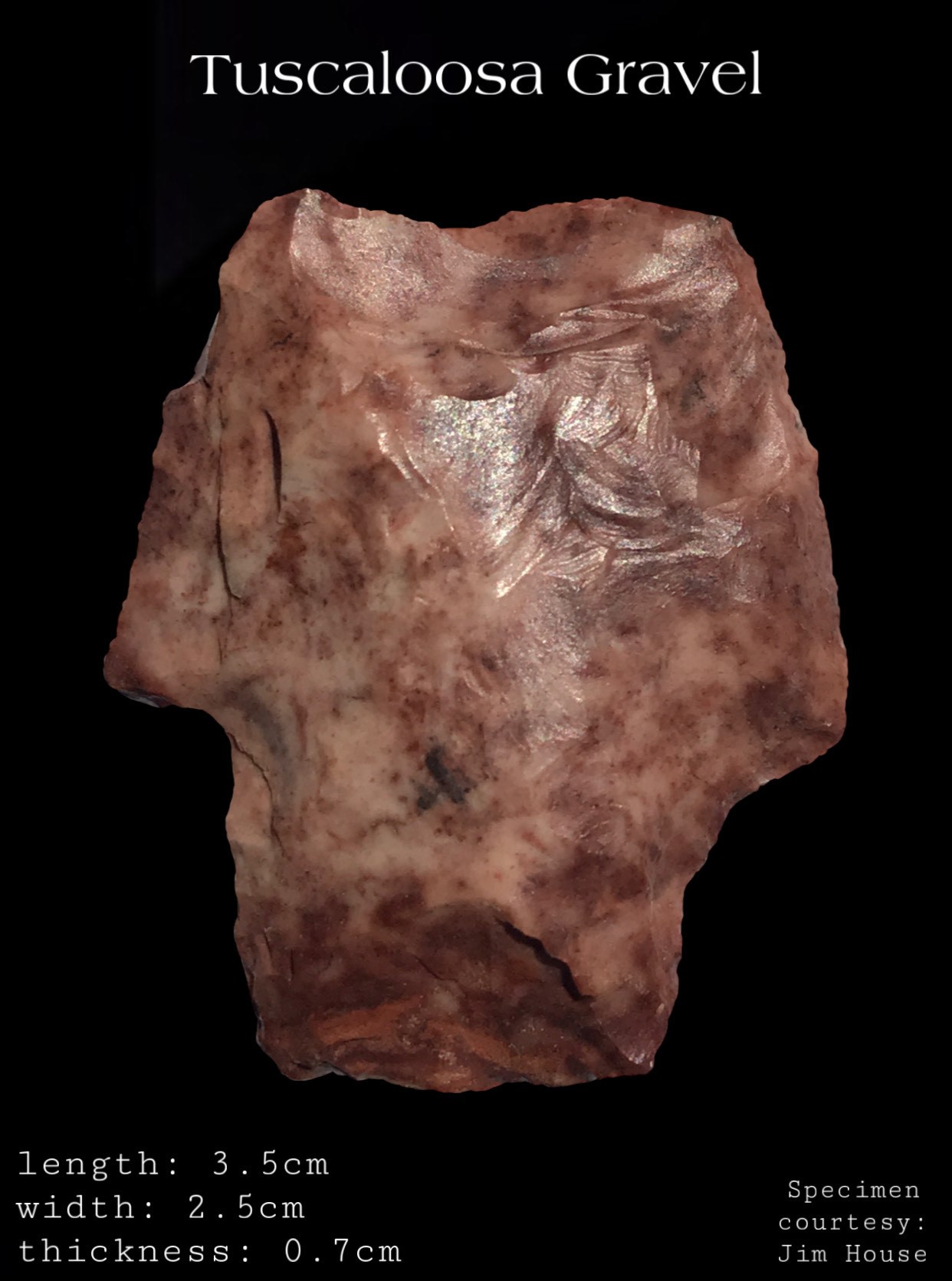

Tuscaloosa Gravels

The outcrops of the Tuscaloosa Formation are Cretaceous in age. The Tuscaloosa Formation contains chert-bearing gravels that were derived from nearby Paleozoic-era limestones. Outcrops of Tuscaloosa gravel occur along the Mississippi-Alabama border, from Tishomingo County south through Lowndes County in Mississippi. Tuscaloosa gravels are predominantly chert, with lesser occurrences of grainy clasts of metamorphic quartz and white vein quartz that were derived from deeper in the Alabama Piedmont to the east. Chert gravel of the Tuscaloosa Formation was derived largely from the erosion of the bedrock of Fort Payne, Tuscumbia, and even possibly Bangor limestones. The Tuscaloosa Formation unconformably on-laps areas bordering the foothills of the Appalachians and the Gulf Coastal Plain. Gravels from the Tuscaloosa Formation were also re-deposited to lower elevations into stream terraces and along stream valleys within the drainage of the Tombigbee River and its tributaries. These chert gravel resources were utilized widely throughout north-central and east-central Mississippi’s Flatwoods region, in the hills of the Wilcox belt, and across the Black Prairie region of northeast Mississippi. This is due to the lack of other suitable naturally available resources occurring in these areas. Chert gravels of the Tuscaloosa Formation vary naturally in color in shades of tan, red, pink, gray, black, brown, yellow, and white. Tuscaloosa chert gravel clasts commonly retain pressure-solution features, called stylolites, from their origins in the bedrock limestone. Stylolites occur as zig-zag patterns in the stone that are typically infilled with secondary quartz and/or chalcedony minerals. These flaws in the rock typically cause problems during the manufacturing of knapped stone tools. Heat-treatment to enhance the knapping properties of the stone was a common practice for processing Tuscaloosa gravel. Heat-treated Tuscaloosa chert gravel typically exhibits a distinctive red and pink mottled appearance with strong contrast between zones separated by the stylolites in the stone.

References: The Upper Cretaceous Deposits of Mississippi Bulletin; Tishomingo County Bulletin; The McCraney Cache

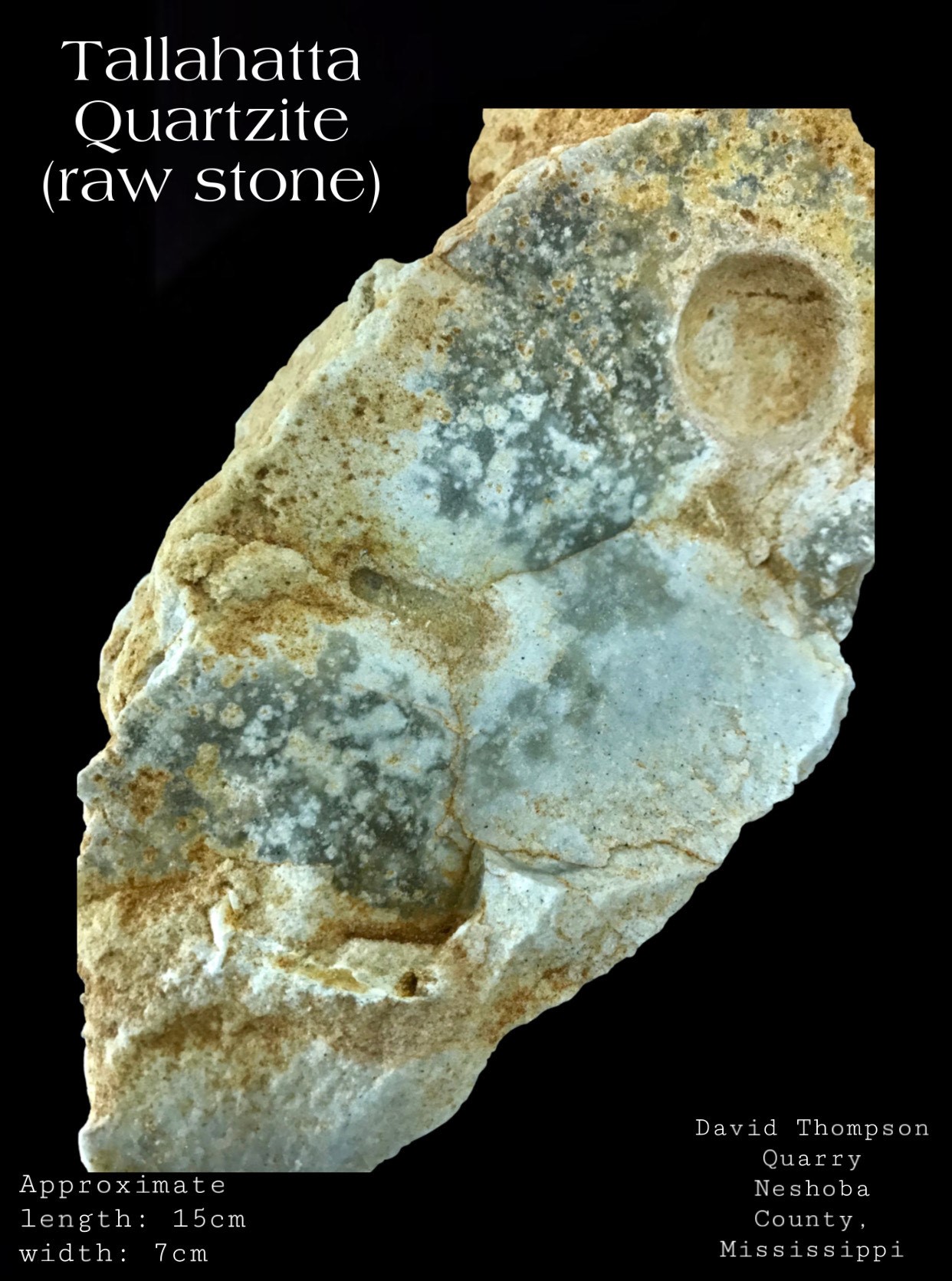

Tallahatta Orthoquartzites

Tallahatta Quartzite was mined extensively from outcrops in east-central Mississippi and west-central Alabama. Tallahatta Quartzite is a silica-cemented, nearly pure quartz sand. Silica cement is predominantly opal-CT with varying amounts of chalcedony, and quartz. Tallahatta quartzite is often translucent and ranges in color from white, green, yellow-to reddish-brown, and black. Mineral inclusions of glauconite and mica are common. Fossil inclusions such as invertebrate burrows typically occur within quartzite beds. Glauconite impurities manifest into “snowflake” patterns in the stone as these mineral inclusions weather from the quartzite. Tallahatta Quartzite varies highly in stability and can weather back to friable sandstone. Because of this, artifacts of Tallahatta Quartzite are commonly referred to as “sugar-quartz” by some collectors. Some Tallahatta Quartzite artifacts remain stable and retain their vitreous appearance. This can be attributed to several factors including a higher stability of silica cement, the lack of glauconite inclusions, or artifacts that are deposited in a consistently wet environment. Tallahatta Quartzite in Mississippi is concentrated, but not restricted to the Basic City Member of the Tallahatta Formation and occurs along the outcrop belt from Neshoba County to the Alabama line. Concentrations of quarry sites can be found along the Chunky River and its tributaries in Lauderdale County, Tallahatta Creek in Newton County, and the Chickasawhay River in Lauderdale and Clarke County. The utilization of Tallahatta Quartzite originated in the Paleolithic cultural period in the absence of other geologic materials suitable for knapping in east-central Mississippi. Tallahatta Quartzite had a wide cultural distribution and has been found on archeological sites throughout Mississippi.

References: Mississippi Geology 14,4; Mississippi Geology 13,3; OFR 284 Geologic Map of the Deemer Quadrangle; Geologic Study Along Highway 80 from Alabama Line to Jackson, Mississippi; Geologic Study Along Highway 45 from Tennesse Line to Meridian, Mississippi; Newton County Bulletin; Lauderdale County Bulletin; Clark County Bulletin

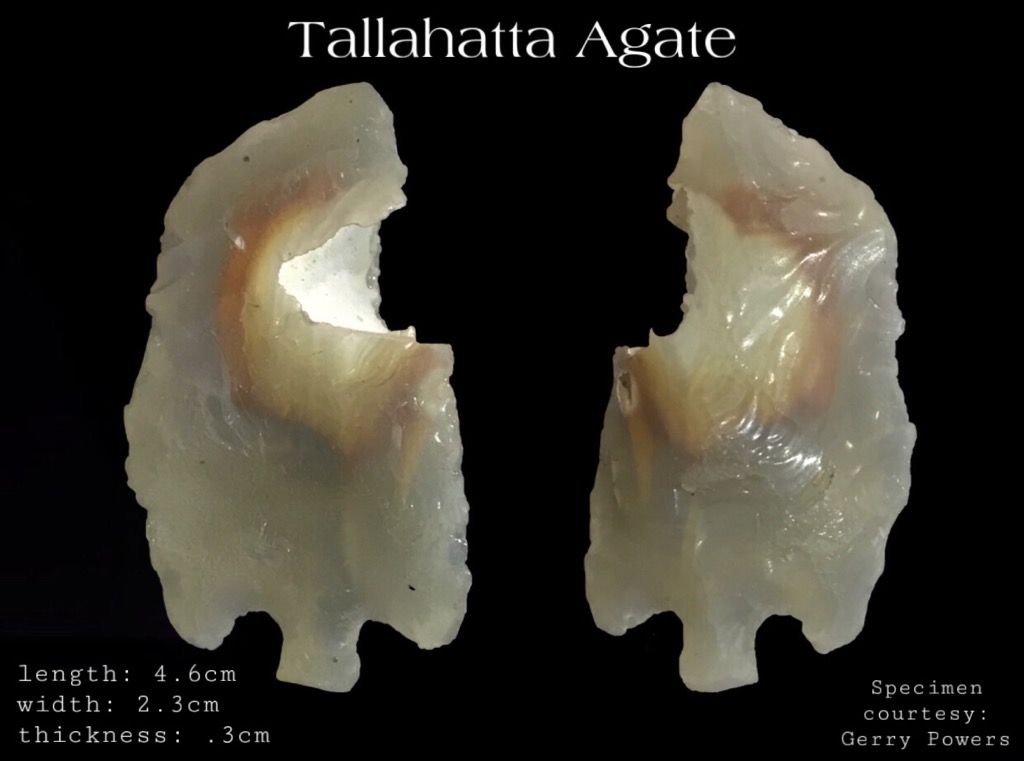

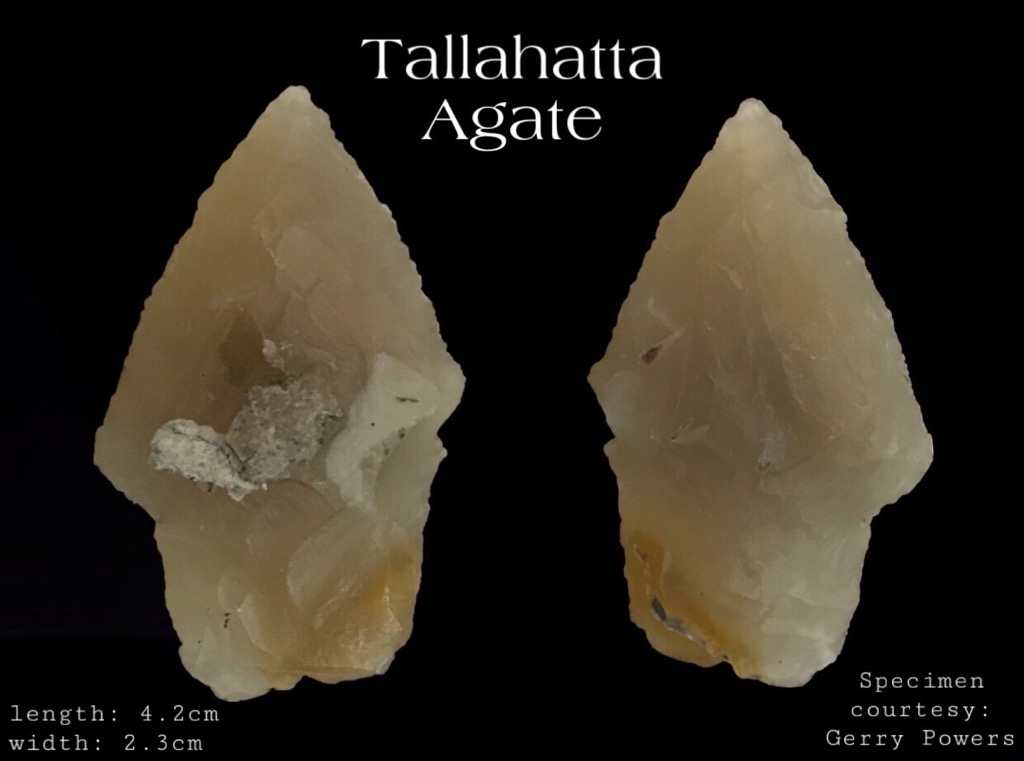

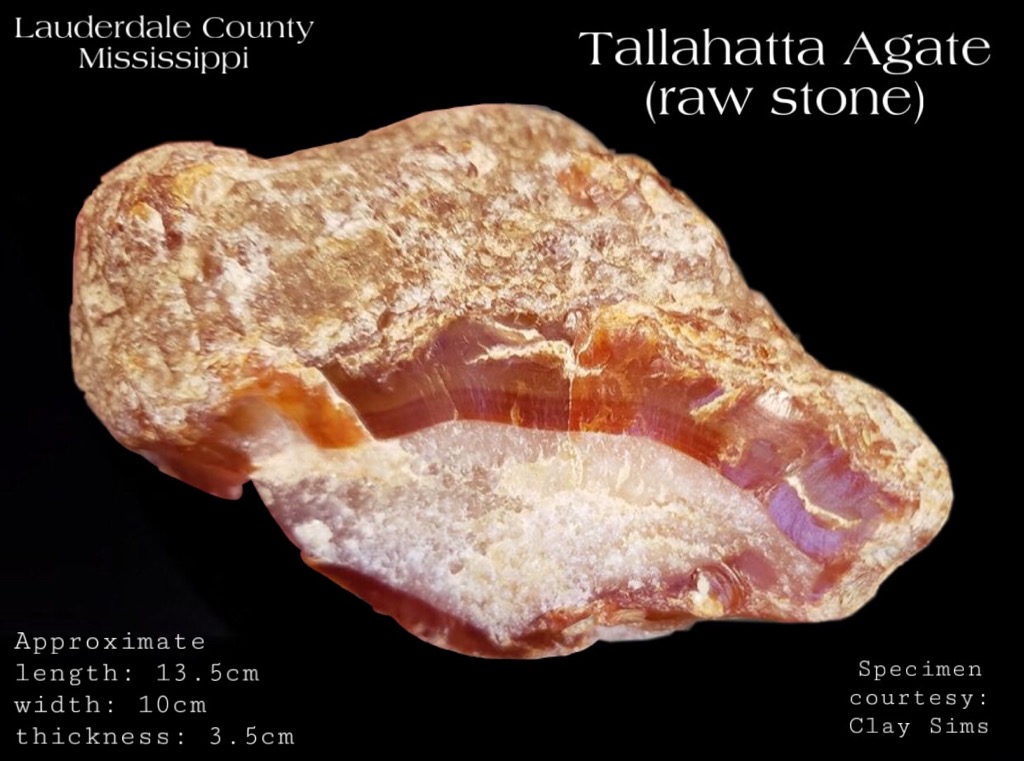

Tallahatta Agates

Tallahatta Agate is an opaline-rich chalcedony found in the Basic City Member of the lower Eocene age Tallahatta Formation in east-central Mississippi and west-central Alabama. This high-quality lithic material is found associated with occurrences of Tallahatta Quartzite as mineralized fillings of joint fractures, fossil burrow casts, and mollusk fossil molds. The stone is translucent yellow to orange in most circumstances but owes its other variations in color to mineral impurities. The natural occurrence of Tallahatta Agate is far scarcer than that of Tallahatta Quartzite and constitutes a rare occurrence in the archaeological record. Because it can be found at the same outcrops, its distribution may mirror that of Tallahatta Quartzite. Tallahatta Agate is remarkably similar in appearance to Florida’s intensely utilized Agatized Coral. Tallahatta Agate can be differentiated by laminar bedding that often inhibits the knapping properties of the stone.

References: Mississippi Geology 14,4; OFR 284 Geologic Map of the Deemer Quadrangle; Geologic Study Along Highway 80 from Alabama Line to Jackson, Mississippi; Geologic Study Along Highway 45 from Tennesse Line to Meridian, Mississippi; Newton County Bulletin; Lauderdale County Bulletin; Clark County Bulletin

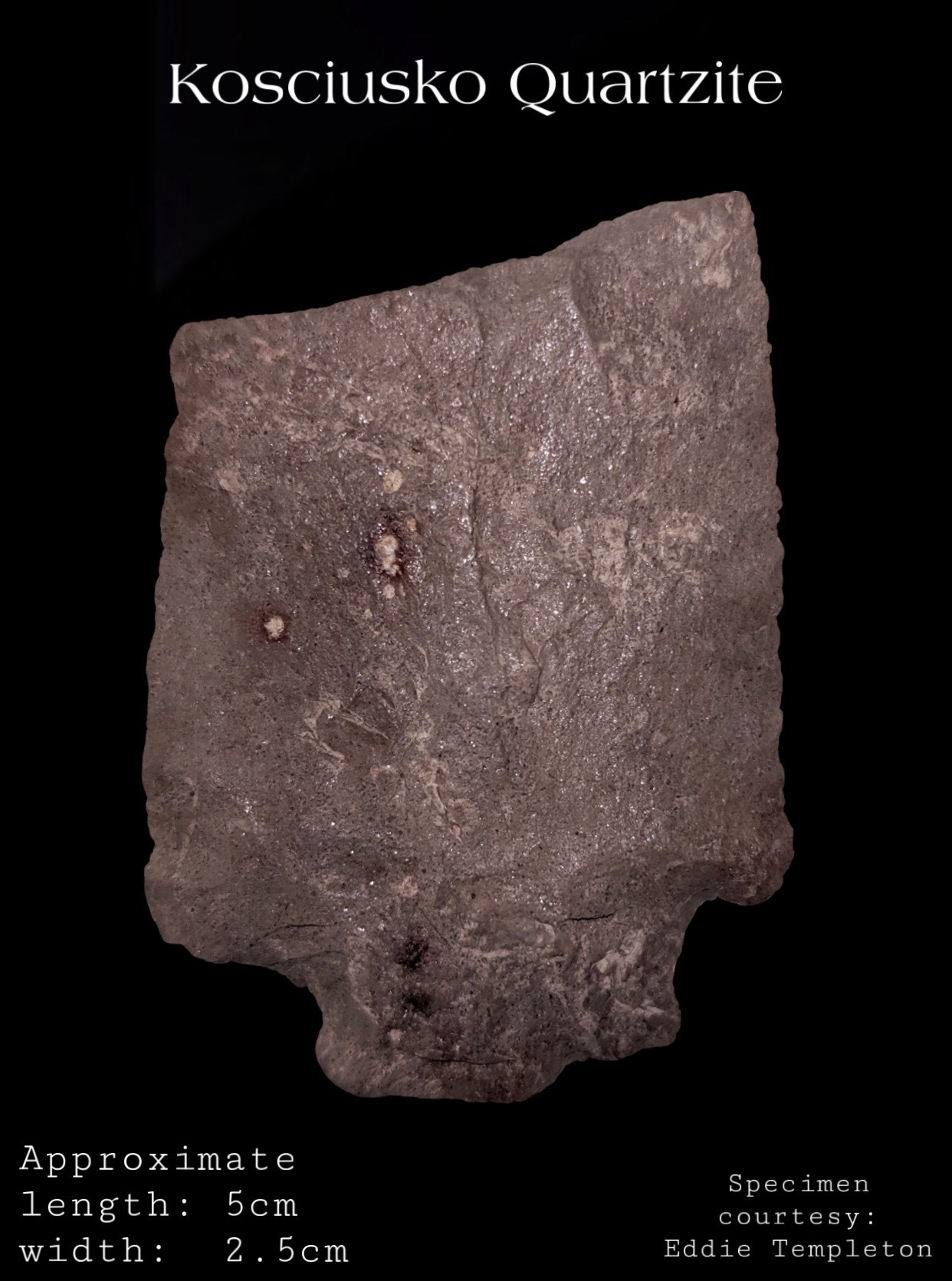

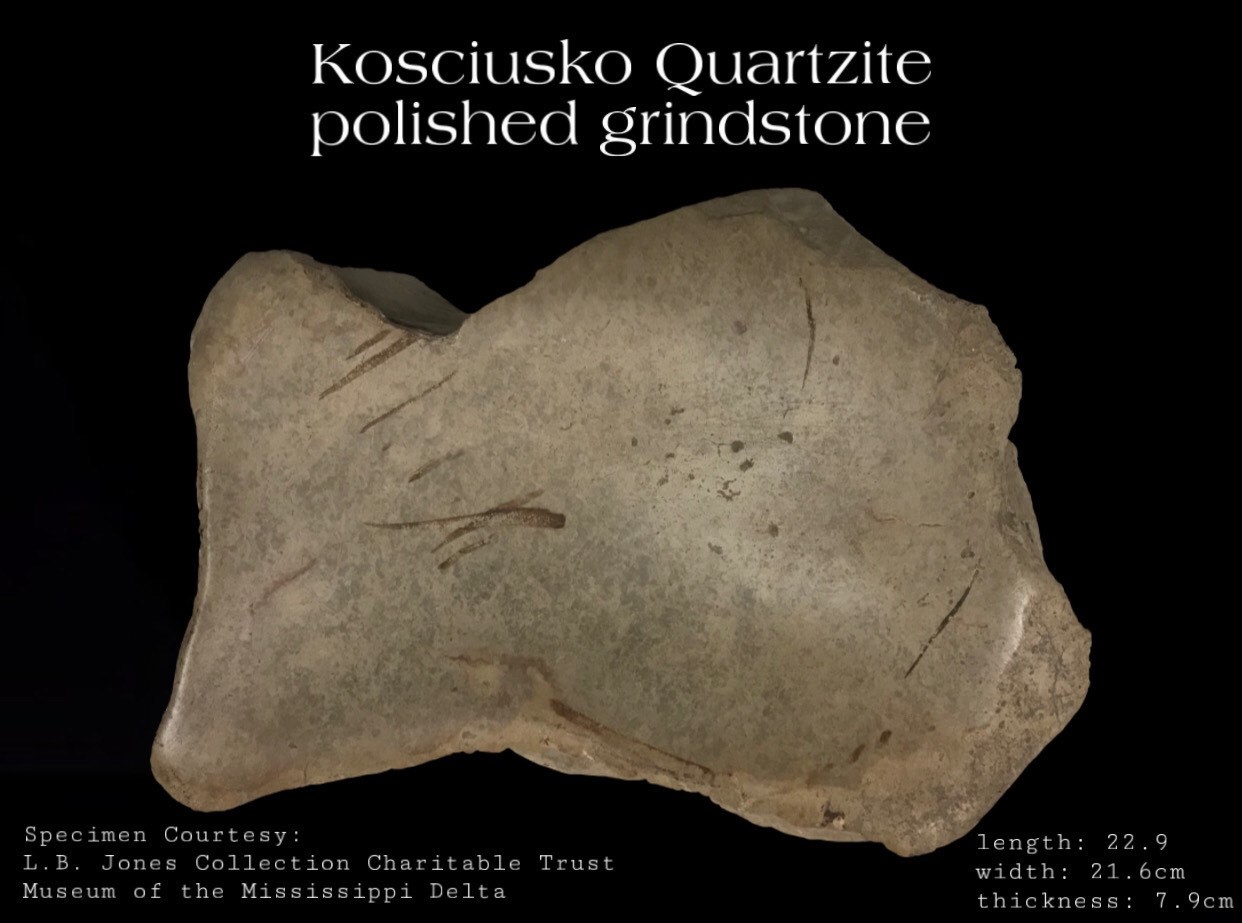

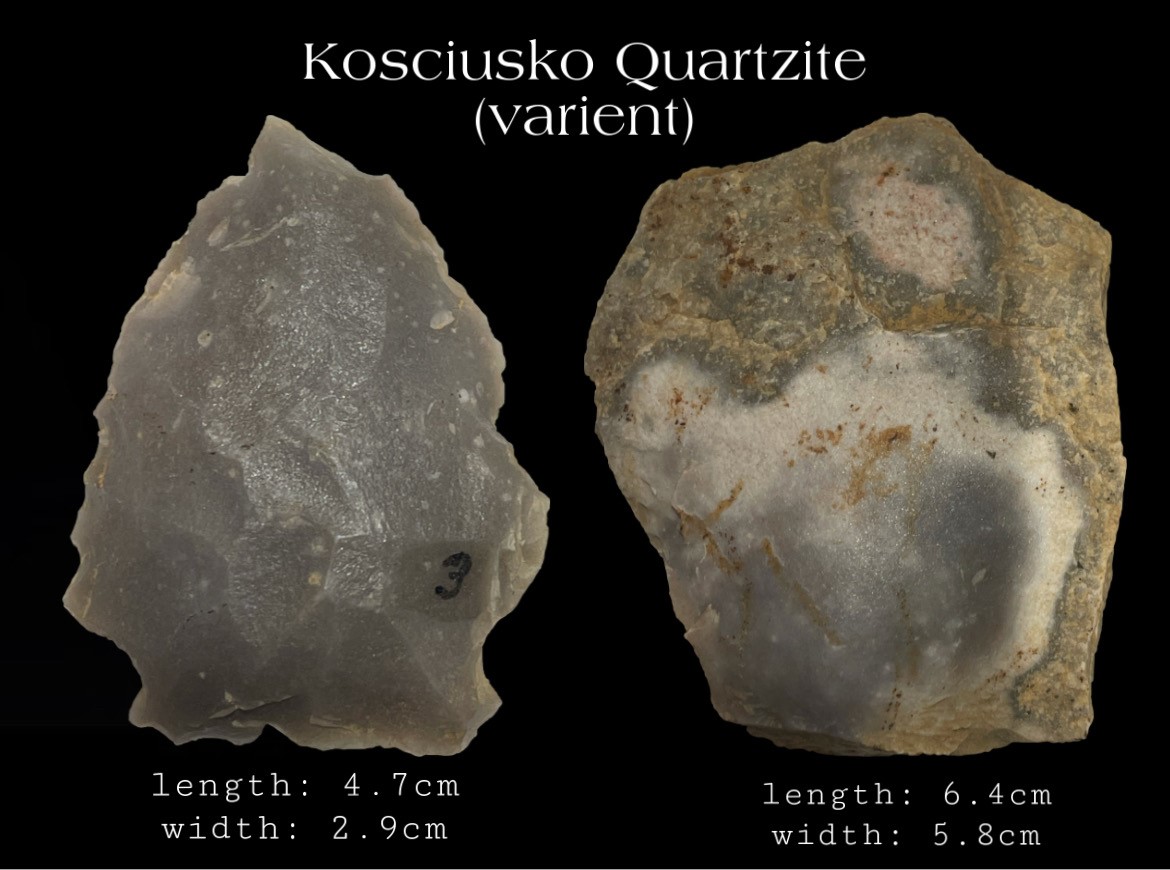

Kosciusko Orthoquartzites

The fine-grained, sandy basal portion of the Eocene age Koscuisko Formation locally contains good-quality orthoquartzites. Most noteworthy are outcrops in the vicinity of the town of Kosciusko in Attala County. Ledges of orthoquartzites have been noted in the Koscuisko Formation across the outcrop belt from Montgomery to Newton Counties near the contact with the underlying Zilpha clays. These typically fine-grained quartzites are very hard. Kosciusko Quartzite is typically gray and is sometimes marbled with light red iron staining. They can be differentiated from other orthoquartzites in that the cementation is a product of the interlocking of sand grains due to quartz overgrowth. In some instances, Kosciusko Quartzite can only be distinguished from chert by microscopic inspection of the stone.

References: Attala County Bulletin

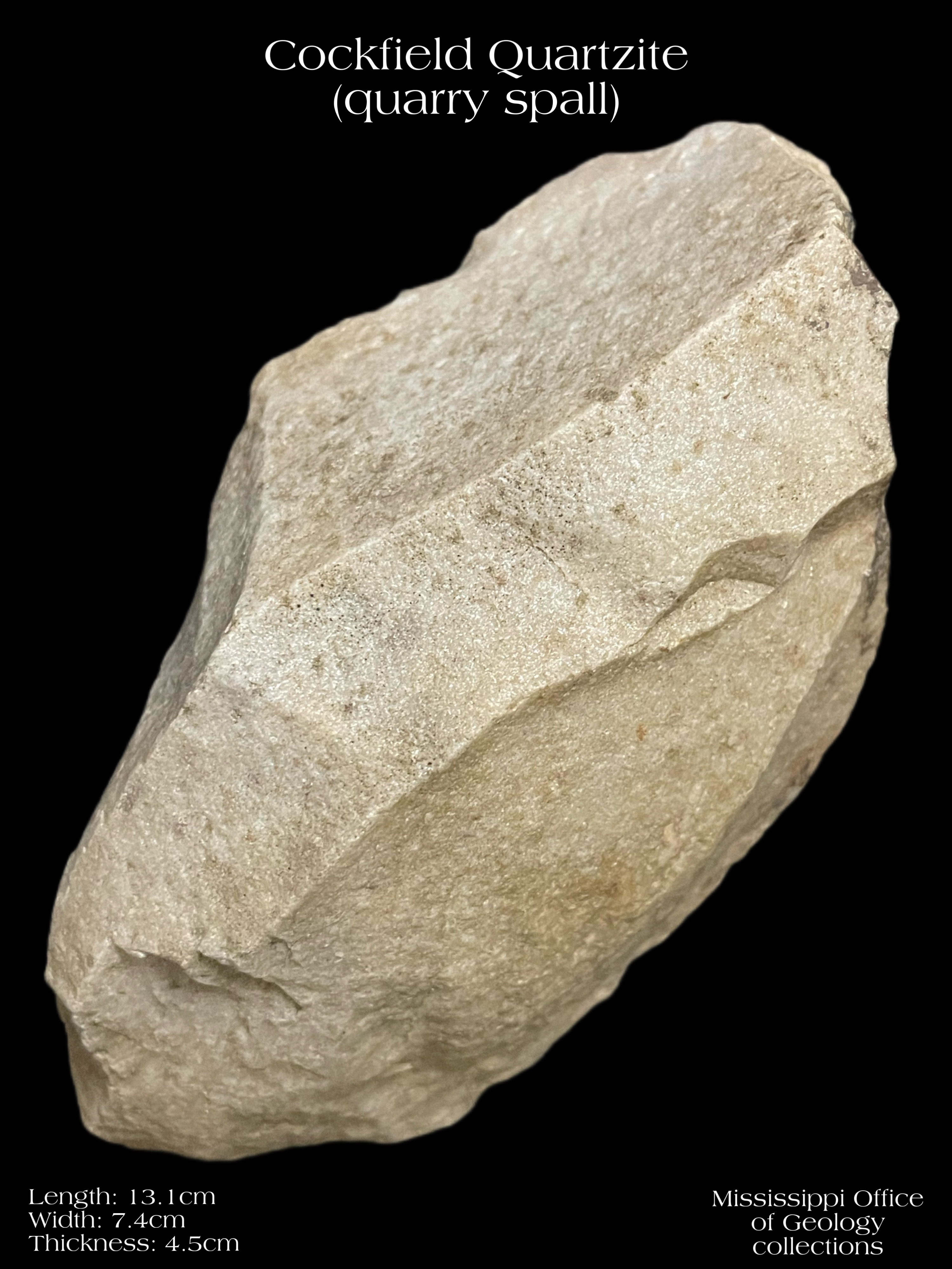

Cockfield Orthoquartzites

Ledges of orthoquartzites have been noted in the lower sands of the Eocene age Cockfield Formation in an isolated string of outcrops along the edge of the loess bluff line, exposed just beneath the Pre-loess Terrace Deposits in Holmes County near town of Tchula. Like the orthoquartzite of the Kosciusko Formation, this fine-grained orthoquartzite is a product of quartz overgrowth interlocking of sand grains. It is light gray and weathers to a khaki color, in some cases speckled with a light red iron staining. It has a strikingly similar appearance to Kosciusko Quartzite and likewise, it is an extremely durable stone. Quarries along the lower reaches of Fannegusha Creek show extensive cultural procurement of Cockfield Quartzite. Little is known about the cultural distribution of the material because geoarchaeological investigations and detailed geologic mapping of Cockfield Quartzite are in their infancy. It is likely that Cockfield Quartzite has been misidentified as Kosciusko Quartzite on archaeological sites in the Mississippi Delta region.

References: The Claiborne Bulletin; OF-290 Geologic Map of the Tchula Quadrangle

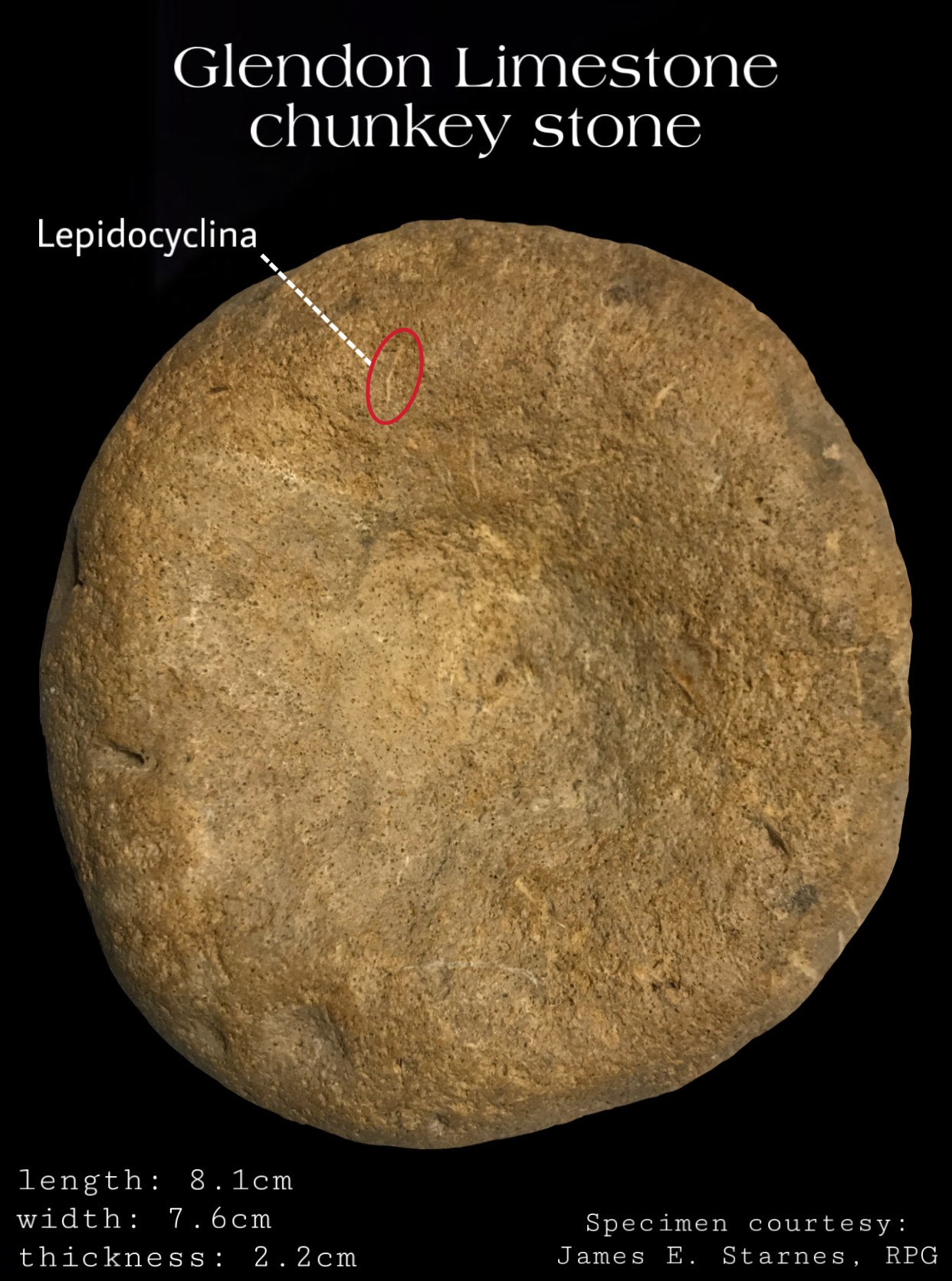

Glendon Limestone

Limestones of Paleozoic, Cretaceous, Paleocene, Eocene, and Oligocene Formations throughout Mississippi have been locally utilized for grindstones, hammer-stones, plummets, pipes, boat-stones, banner-stones, etc. They can be traced back to their outcrop of origin by their diagnostic invertebrate fossil content such as foraminifera. The most widely utilized and traded limestone resource from Mississippi is the Glendon Limestone. It can readily be identified by the presence of the abundant large foraminifera, Lepidocyclina. Hard ledges of semi-crystalline Glendon Limestone occur in a narrow belt of craggy hills through central Mississippi from Warren County to Wayne County.

References: Marls and Limestones of Mississippi Bulletin; Cement and Portland Cement Materials of Mississippi Bulletin; Mississippi Agricultural Limestone Bulletin; Lower Oligocene Gastropoda, Scaphopoda, and Cephalapoda of the Vicksburg Group in Mississippi; Lower Oligocene Bivalvia of the Vicksburg Group in Mississippi

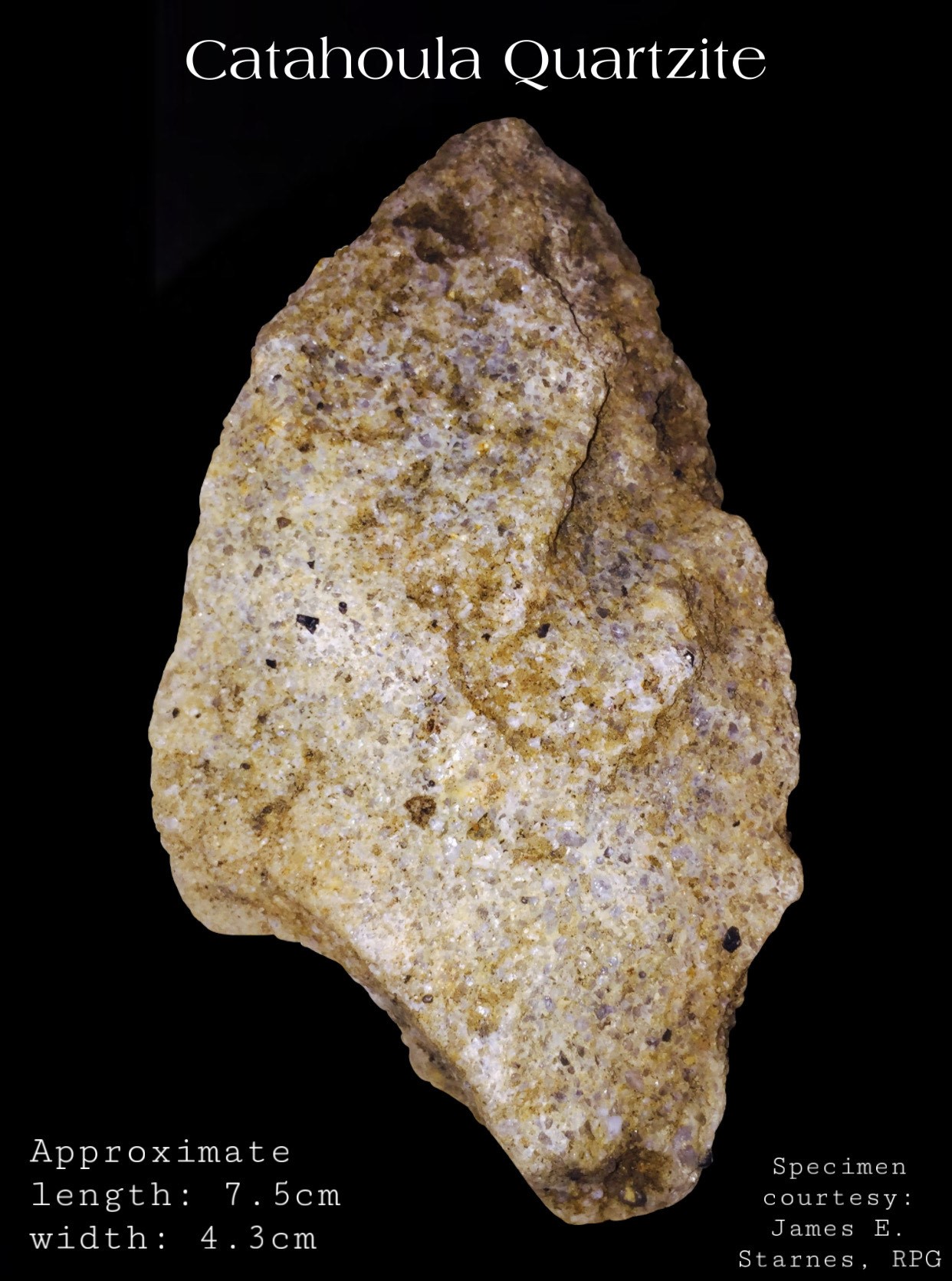

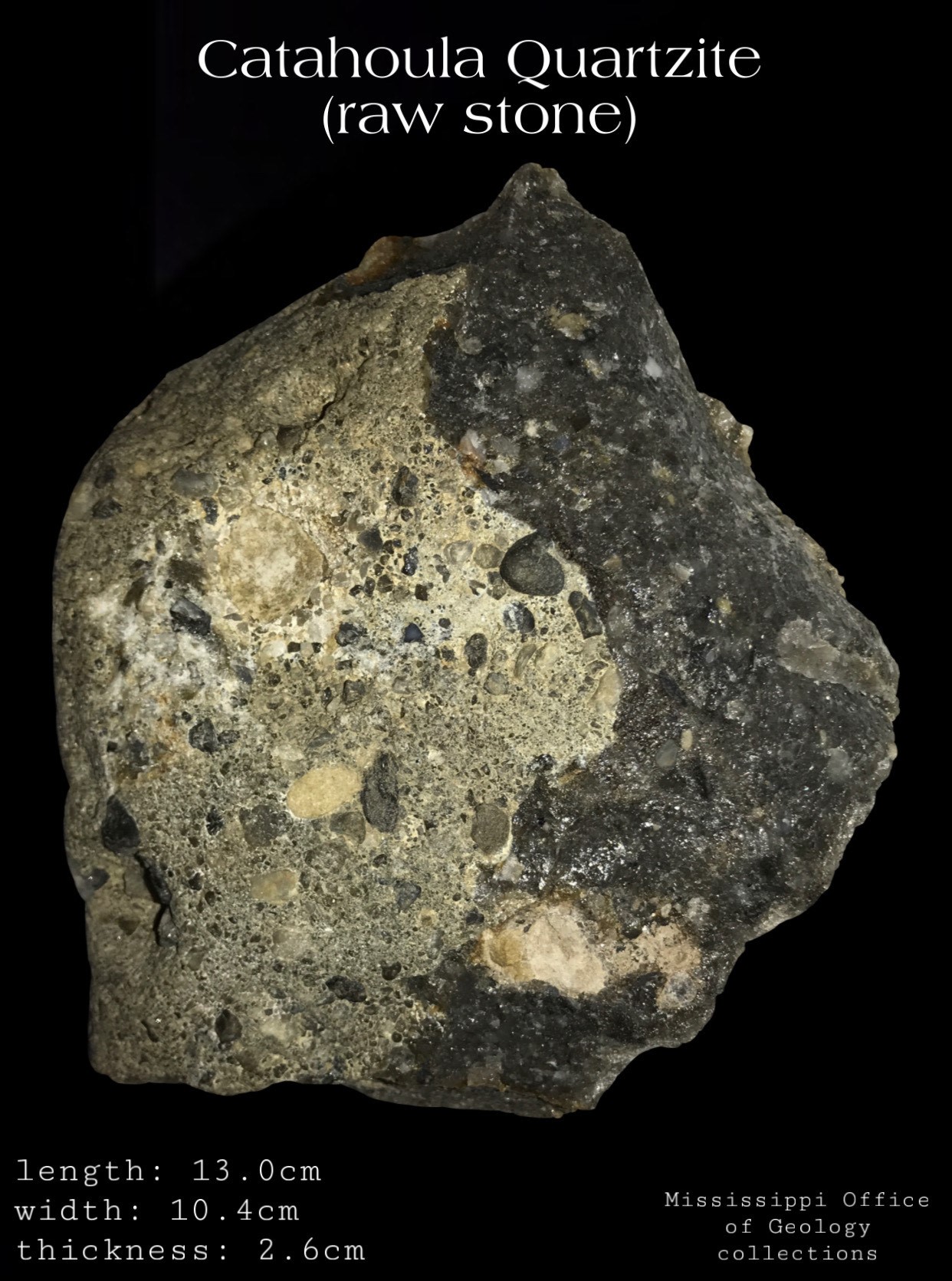

Catahoula Orthoquartzites

The Catahoula Formation outcrops in a broad band throughout south-central Mississippi from Claiborne to Wayne County. The shallow marine to deltaic deposits of the Catahoula is overlain by similar lithologies of the Hattiesburg Formation and unconformably underlain by the limestones and marls of the Vicksburg Group. The Catahoula Formation is comprised of alternating beds of sandstone, siltstones, and clay. The occurrences of hard sandstones exist throughout much of the outcrop belt of the formation. This induration is due to an abundance of opaline cement likely derived from volcanic ash. In certain geological settings, the concentration of opaline cement within the sandstones is sufficient to form an orthoquartzite. The occurrence of Catahoula Quartzite seems to be isolated to the western portion of the formation’s outcrop belt. It has been described as far east as Rankin County, but occurs more abundantly in Copiah, Hinds, and Claiborne Counties. Fresh, un-weathered Catahoula Quartzite has a vitreous texture, and in most cases is translucent. It can vary from colorless to gray, tan to brown, and even black. It weathers to white sandstone with the cement having the appearance of congealed milk under magnification. Some examples of this quartzite tend to be more stable than others and a high degree of this variability can be seen within a single outcrop. Catahoula quartzite is much like Tallahatta Quartzite. It can be differentiated from Tallahatta Quartzite by the presence of black, angular chert sand grains, giving the stone a “salt-and-pepper” appearance. Chert and quartz pea gravel inclusions can be present in coarser-grained varieties of the stone.

References: Claiborne County Bulletin; Hinds County Bulletin; Rankin County Bulletin; Copiah County Bulletin

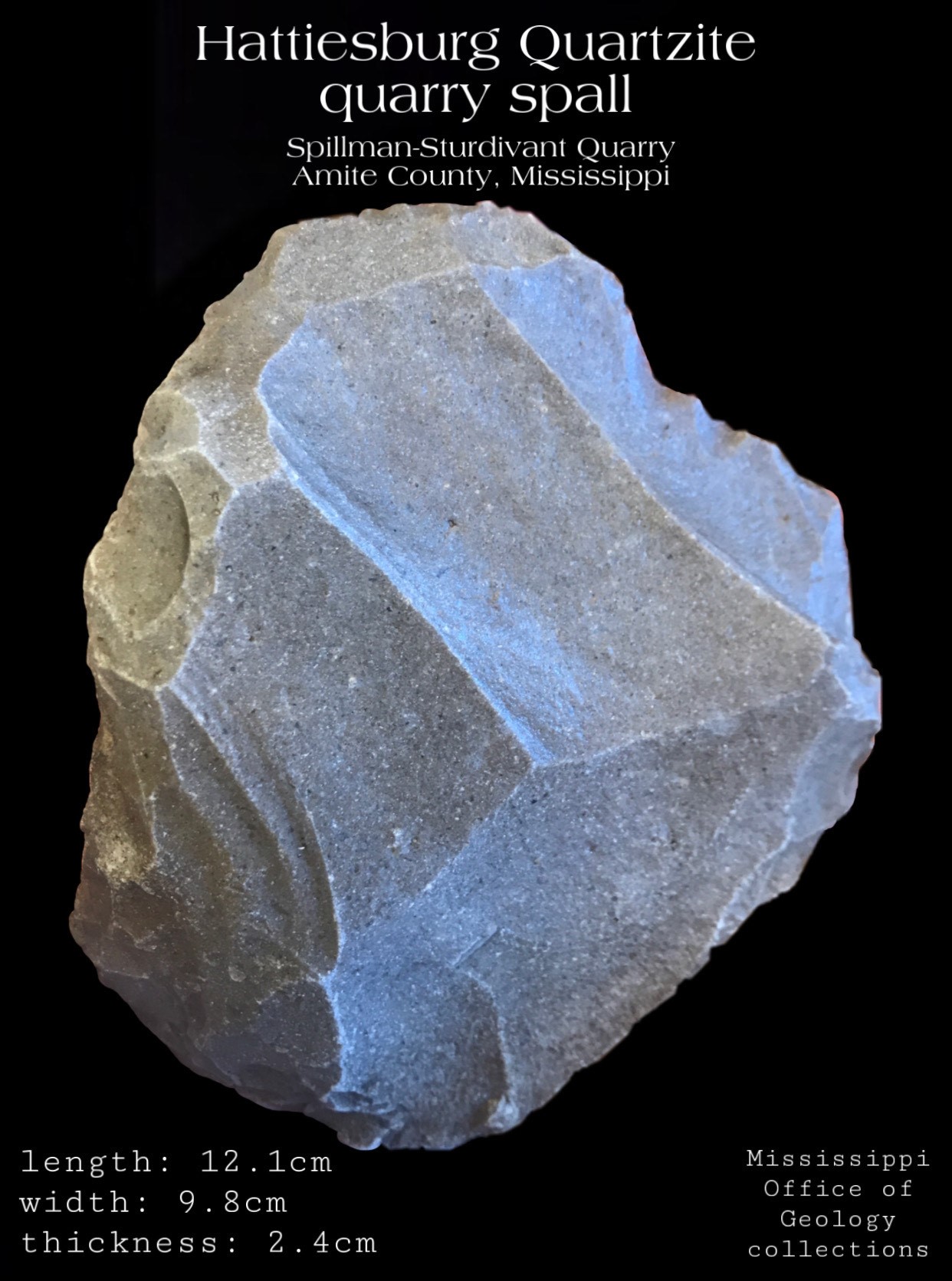

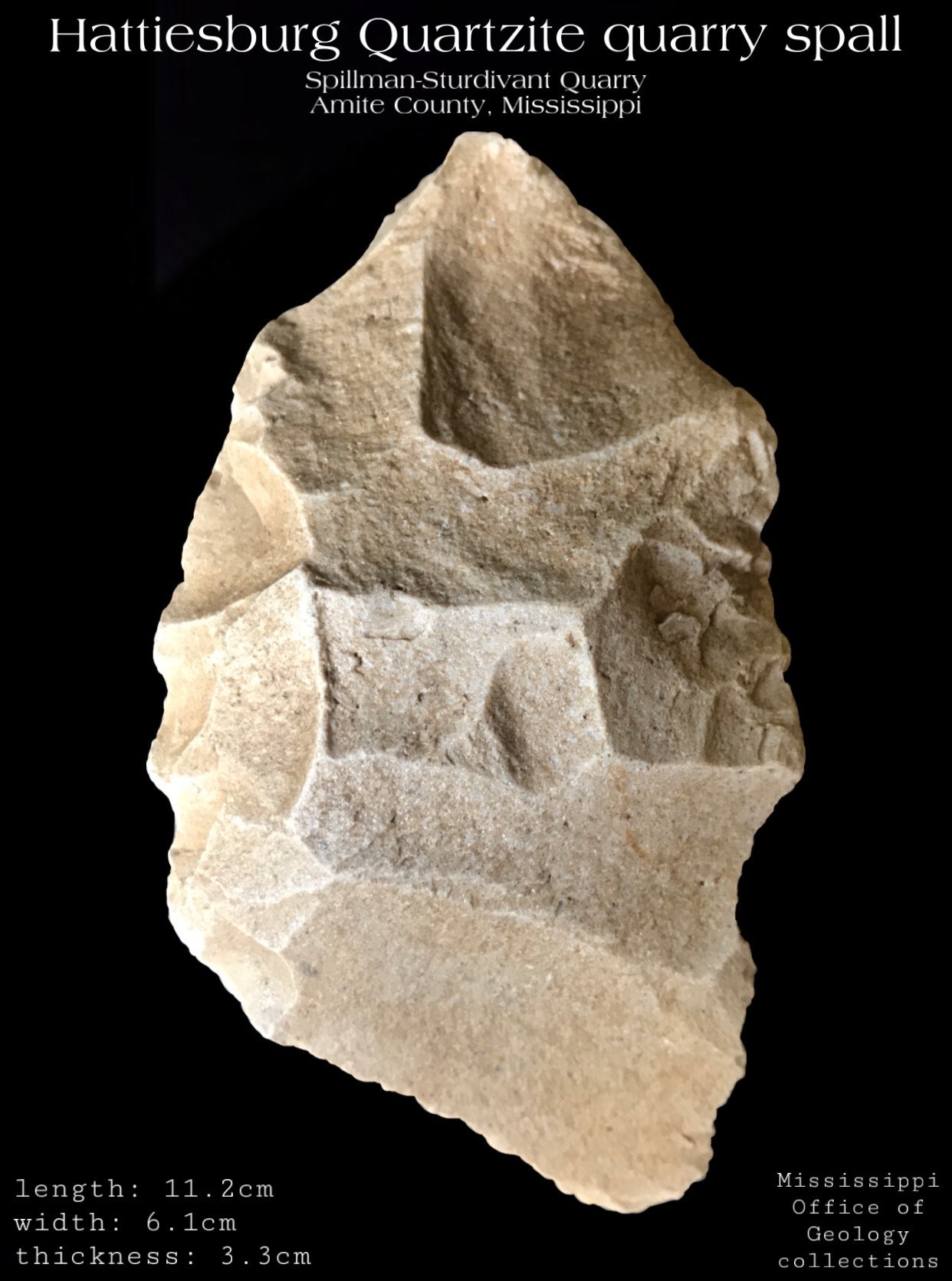

Hattiesburg Orthoquartzites

Hattiesburg Quartzite is a Miocene-age orthoquartzite characterized as a hard, gray to brown-colored, opal-cemented, quartzitic siltstone or fine-grained sandstone. This material commonly contains numerous dissolution vugs that are often hollow, or opal filled. Fresh Hattiesburg Quartzite exhibits an excellent conchoidal fracture that is incomparable to other high-quality natural resources in Mississippi. In artifacts, the stone may weather, differentially or completely, to a friable, light gray to white colored, fine-grained stone that may be uniform or slightly marbled in appearance. In some cases, the weathered material is mottled pink or purple. The only known outcrops of Hattiesburg Quartzite are located along the Homochitto River Valley in Franklin and Amite counties, all of which show signs of extensive quarrying. Little is known about the cultural context from the debris at these quarry sites, or from the nearby material-reduction sites associated with these quarries. This is due to the general lack of culturally diagnostic artifacts at these types of sites. Also, not much is known about the cultural distribution of Hattiesburg Quartzite due to a lack of identified samples in other previously recorded artifact assemblages. Fragments of Sioux Quartzite hammer stones, likely from the gravels of the Homochitto River, have been found at Hattiesburg Quartzite quarries and reduction sites. Sioux Quartzite was utilized to quarry and process the raw Hattiesburg Quartzite.

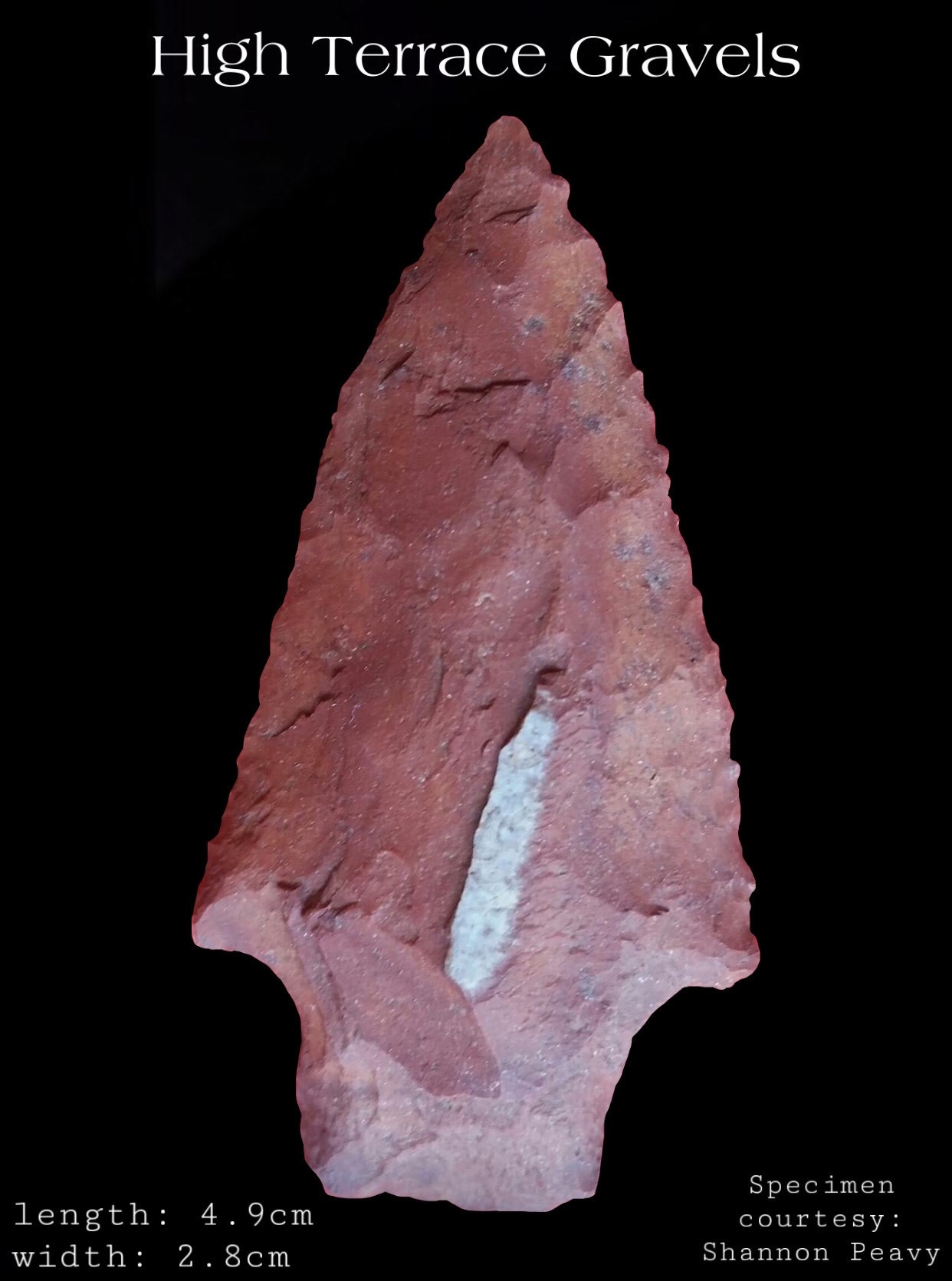

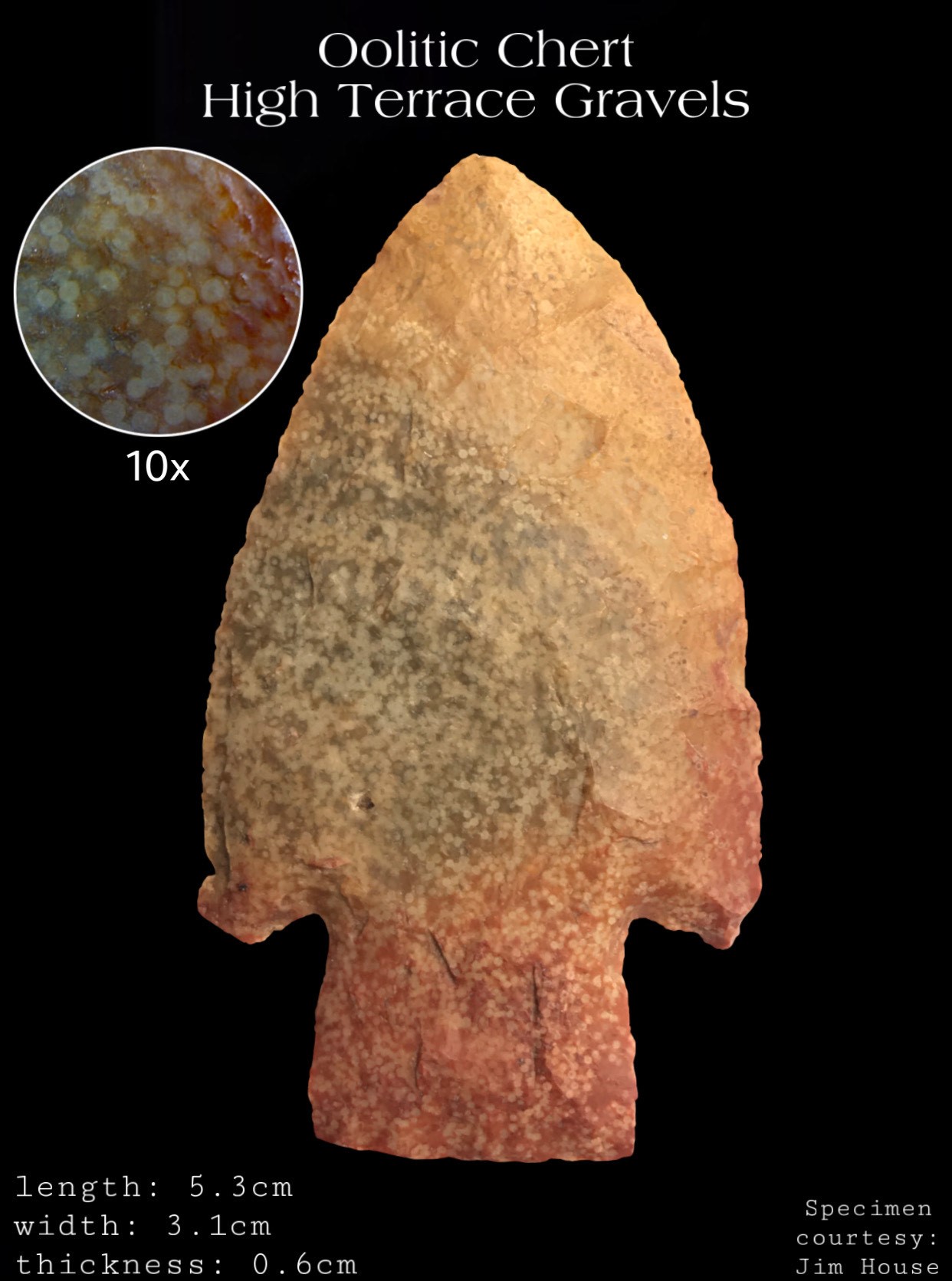

High Terrace Gravels

Sand and gravel deposits of multiple age terrace units, once mapped as the “Citronelle Formation,” sporadically cover much of the southern third of Mississippi. The highest of these deposits are benched above a horizon at approximately 400 feet above sea level and unconfirm-ably overly older bedrock units. This is best expressed in the vicinity of Crystal Springs in Copiah County and south through Brookhaven in Lincoln County. Graveliferous terraces at higher elevations east of the Pearl River, in such places as Simpson County, are also included in this designation. These gravels dramatically decrease in abundance, size, and quality southeastwardly, away from the axis of the Mississippi Embayment. These terraces were deposited by ancient rivers of a pre-Pleistocene ancestral system, prior to the evolution of the Mississippi River in the Pleistocene. These gravels predominantly consist of honey-colored chert derived from marine Paleozoic bedrock of the Tennessee/Ohio River valleys. Gravel clasts from this region typically do not exceed 90mm in diameter. Chert gravel clasts are typically highly weathered and exhibit a thick, porous, chalky, and tripolitic cortex. In some instances, the chert gravel is weathered and leached to such extremes that it is not a viable lithic resource. Heat treatment is typical for the processing of this chert resource giving it shades of red to pink but does not always affect its color or its luster. These gravels are often fossiliferous, containing the invertebrate remains of crinoids, corals, brachiopods, and bryozoans. They can also exhibit a wide variety of sedimentary structures such as oolites, carbonate sands, and bedding structures. High terrace gravels contain varieties of quartz, quartzite, agate, carnelian, jasper, and petrified wood. The gravel resources are confined to the basal portions of these units. The basal gravels are masked by finer-grained sediments present higher in the geologic section throughout the areal extent of the terrace. The high terraces once blanketed larger areas throughout the southern third of Mississippi but have since been heavily eroded. High Terrace Gravels have been reworked into younger river terraces and the modern alluvium of streams. Gravels similar to High Terrace Gravel exist in discontinuous beds at numerous outcrops of Miocene to early Pliocene age formations in south Mississippi. These gravels have also been misattributed as “Citronelle Formation.” These Miocene and early Pliocene gravels are not distinguished in this book as detailed geologic mapping is ongoing to identify and differentiate them.

References: Copiah County Bulletin; Rocks and Fossils Found in Mississippi’s Gravel Deposits; OF-285 Surface Geology of Jackson County, Mississippi

Ironstone

Many exposures of geologic formations and terrace deposits throughout Mississippi contain ironstone in some combination of ferruginous sandstone, siltstone, claystone, or conglomerate. These are cemented by the minerals limonite, siderite, or goethite. Carved ironstones and even those of knapping-quality have been recorded from various pre-historic archaeological contexts throughout Mississippi. Ironstone utilization was more common where other more suitable size and quality stone sources were scarce. Ironstone can range from soft and easily worked to a competent and hard stone. Naturally occurring ironstones saw widespread cultural utilization by the Indigenous peoples as peck, ground, and even beautifully polished artifacts.

References: Preliminary Report on Iron Ores of Mississippi Bulletin; Lafayette County Iron Ores Bulletin; Webster County Iron Ores Bulletin; An Investigation of Mississippi Iron Ores Bulletin; Wayne County Bulletin

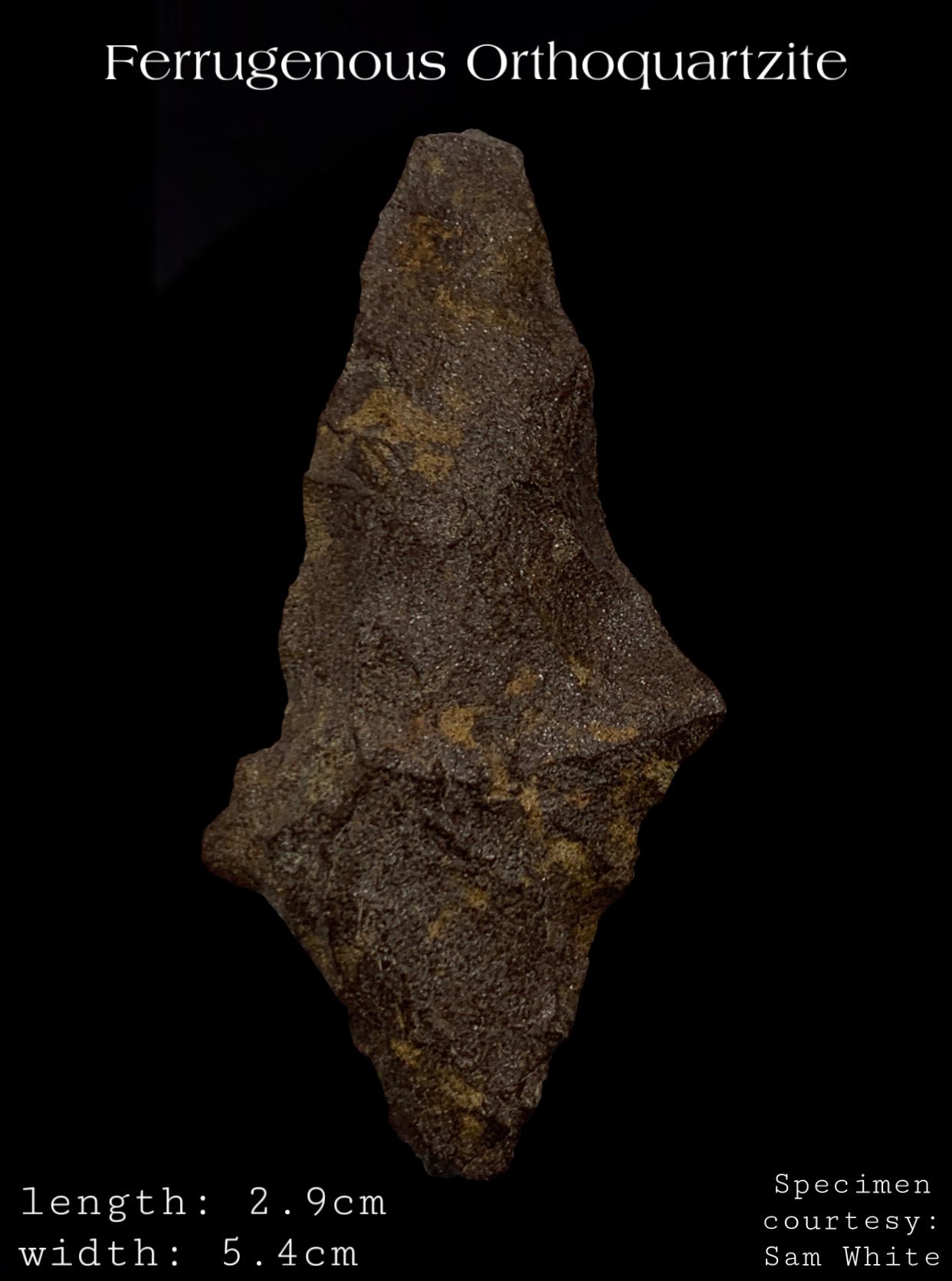

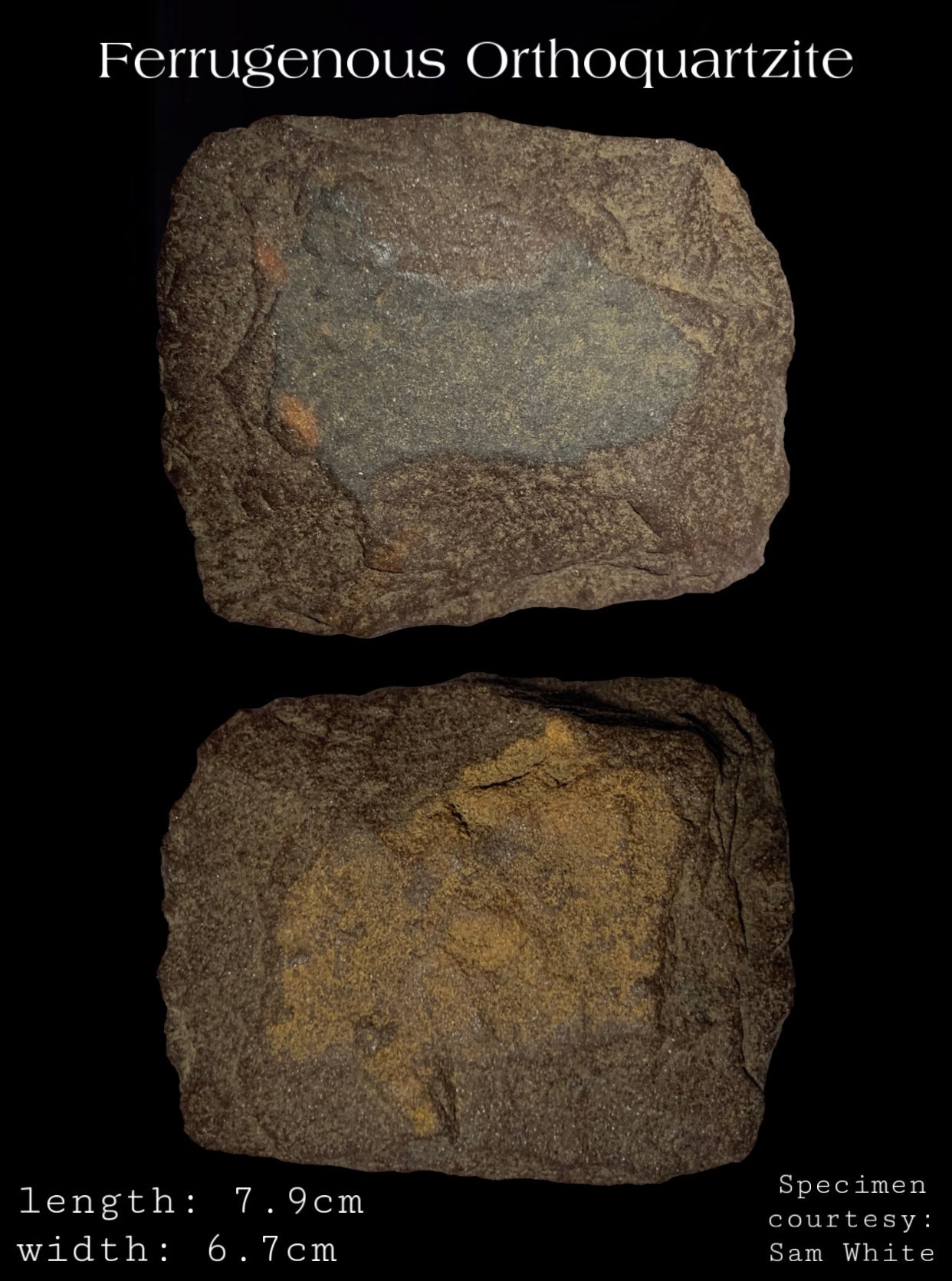

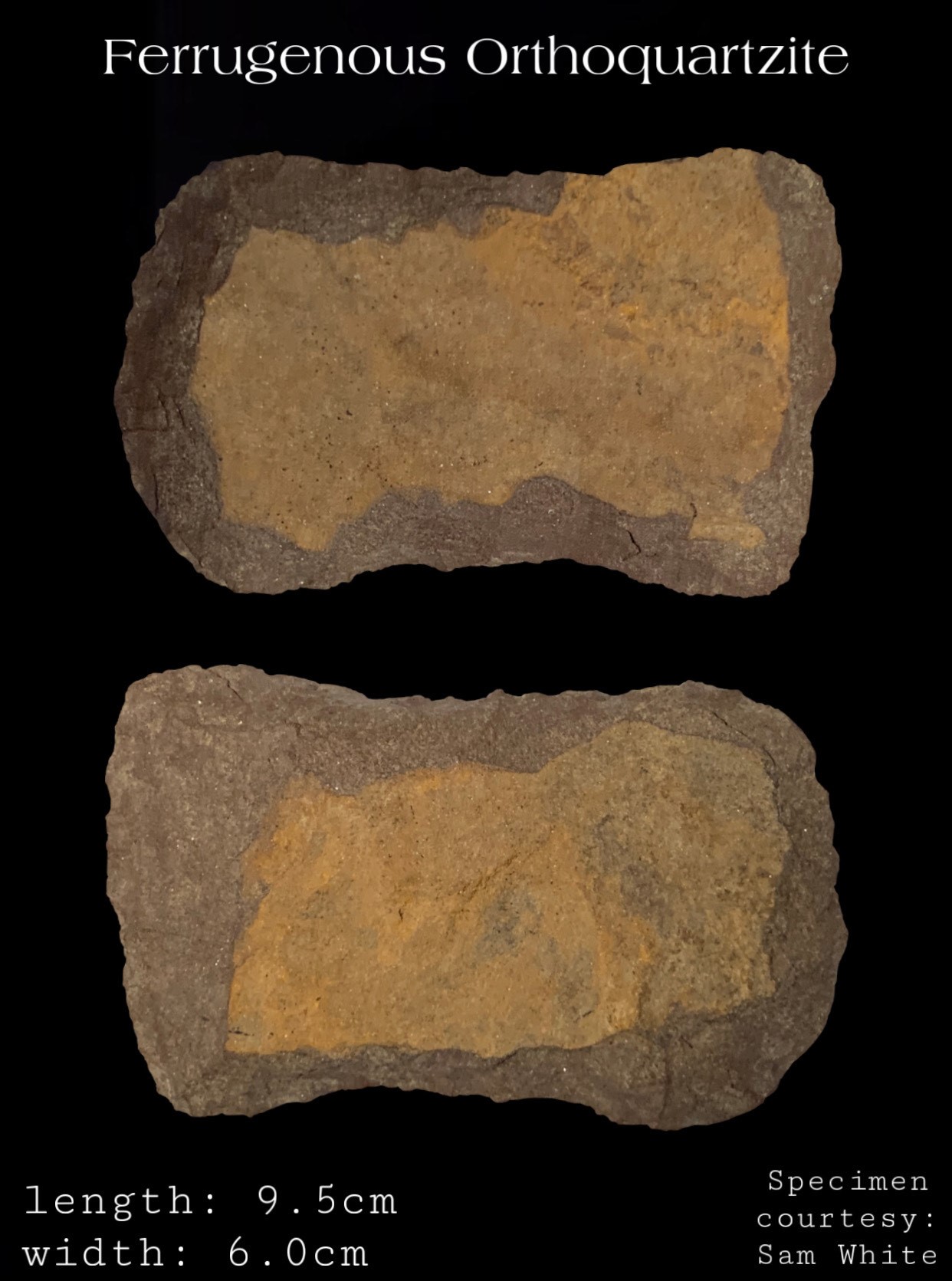

Ferrugenous Orthoquartzite

Ferrugenous Orthoquartzite is an atypical orthoquartzite that does not conform to the classic mineralogical definition of a quartzite, but scientists have recently began distinguishing it based on its mechanical properties. Ferrugenous orthoquartzite is a type of ferruginous sandstone that is sufficiently cemented with iron minerals, particularly the strong bonds created by goethite, to break preferentially across the quartz sand grains to exhibit a predictable subconchoidal to conchoidal fracture. A goethite-cemented Ferruginous Orthoquartzite was extensively quarried for its knapping qualities in southeast Mississippi from stream terraces along the lower reaches of the Leaf River and Chickasawhay River watersheds. Ferrugenous Orthoquartzite has its highest concentration of occurrence on prehistoric Native American archaeological sites in southeast Mississippi in Wayne, Greene, Jones, and Perry Counties. The utilization of Ferrugenous Orthoquartzite as projectile points began as early as Dalton style points in the late Paleoindian cultural period and likely continued to the Woodland cultural period. Ferrugenous Orthoquartzite probably fell out of favor as more suitable material became necessary to produce smaller projectile points for use in bow and arrow. Ferrugenous Orthoquartzite is generally considered a poor-quality material for knapping but was extensively utilized in southeast Mississippi because of the lack of other naturally occurring quality resources such as chert gravel.

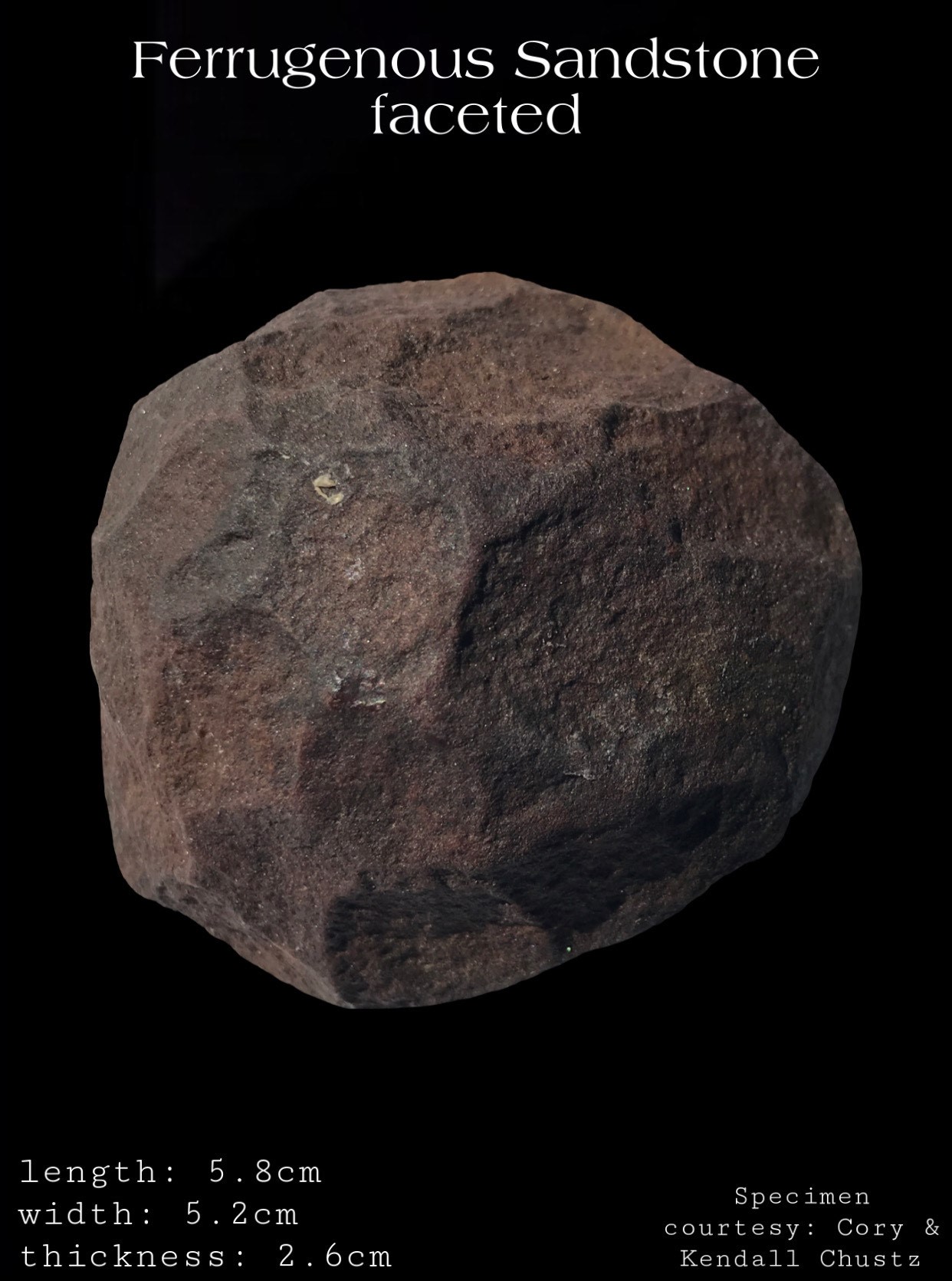

Ferrugenous Sandstone

Ferruginous sandstone is a quartz sandstone cemented with the iron minerals limonite and/or goethite. It can be coarse to fine-grained and even conglomeratic containing quartz and/or chert gravel. It is typically dark reddish-brown. It is one of the most common stones occurring throughout Mississippi. Ferruginous sandstones form from the preferential movement of shallow groundwater as locally cemented zones, entire beds, or as cylindrical tubes called “ironstone piping.” Ferruginous sandstone is one of the most common non-knapped stone types found on archeological sites in Mississippi. It was utilized in a variety of ways including grindstones.

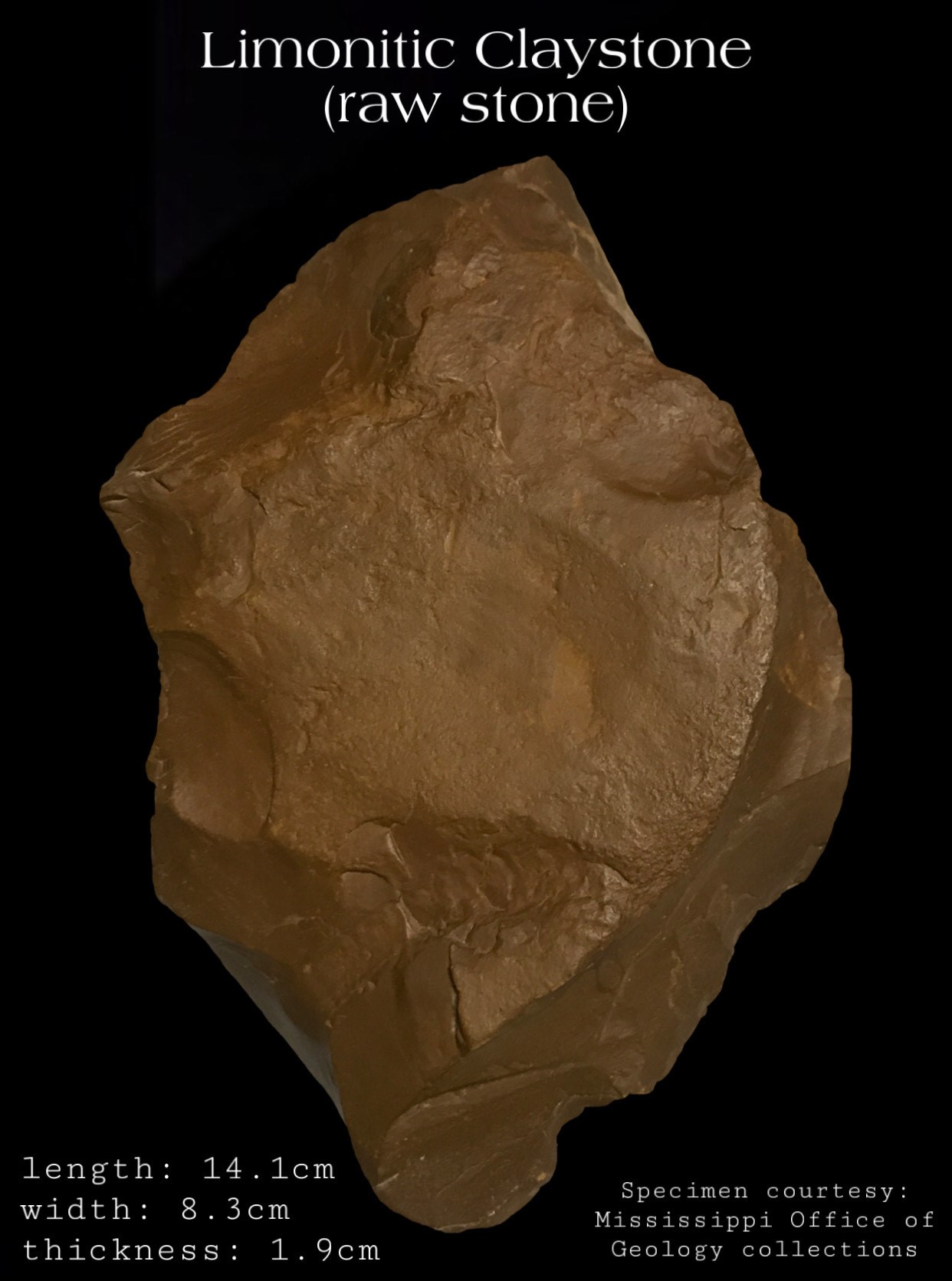

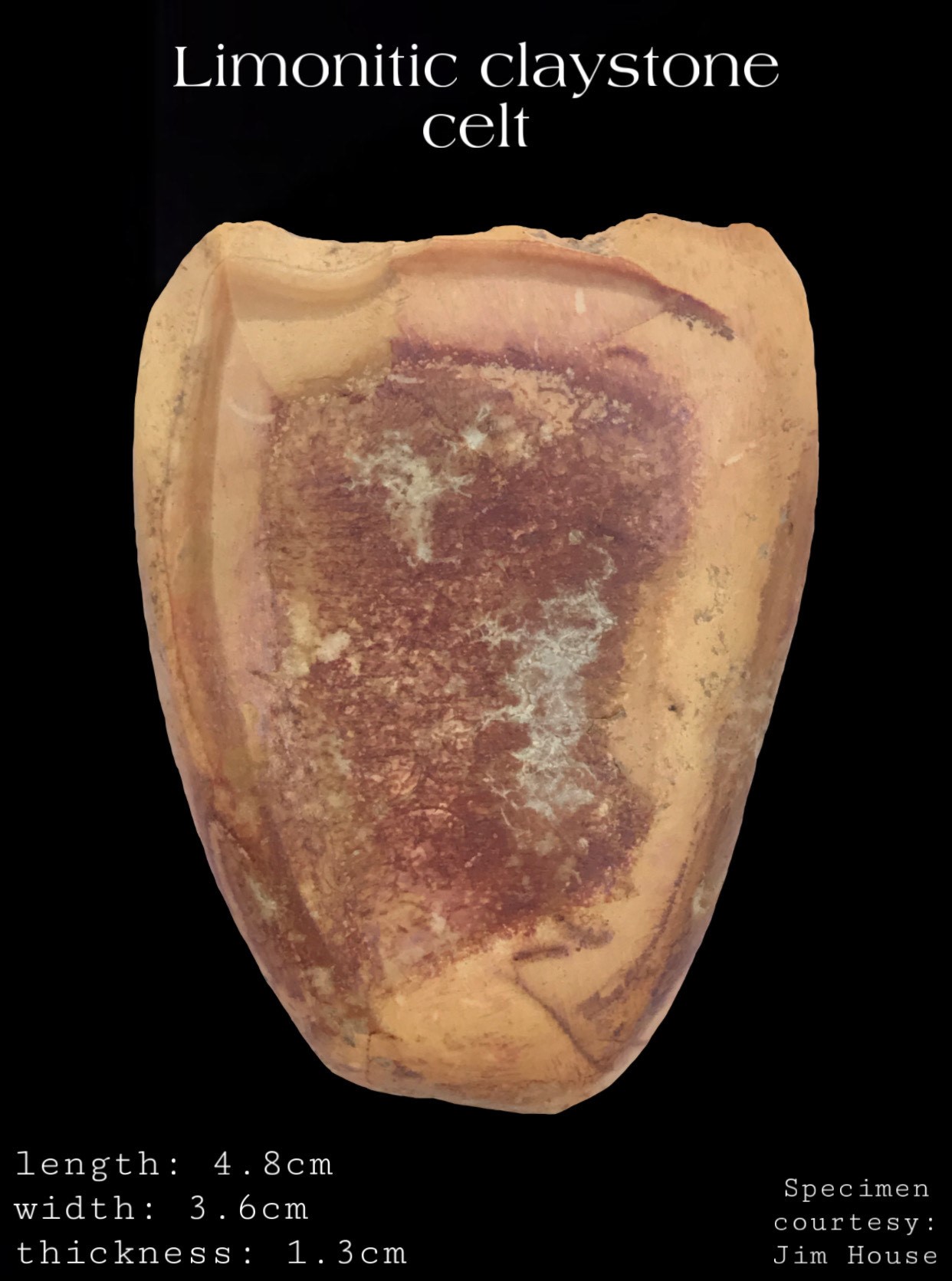

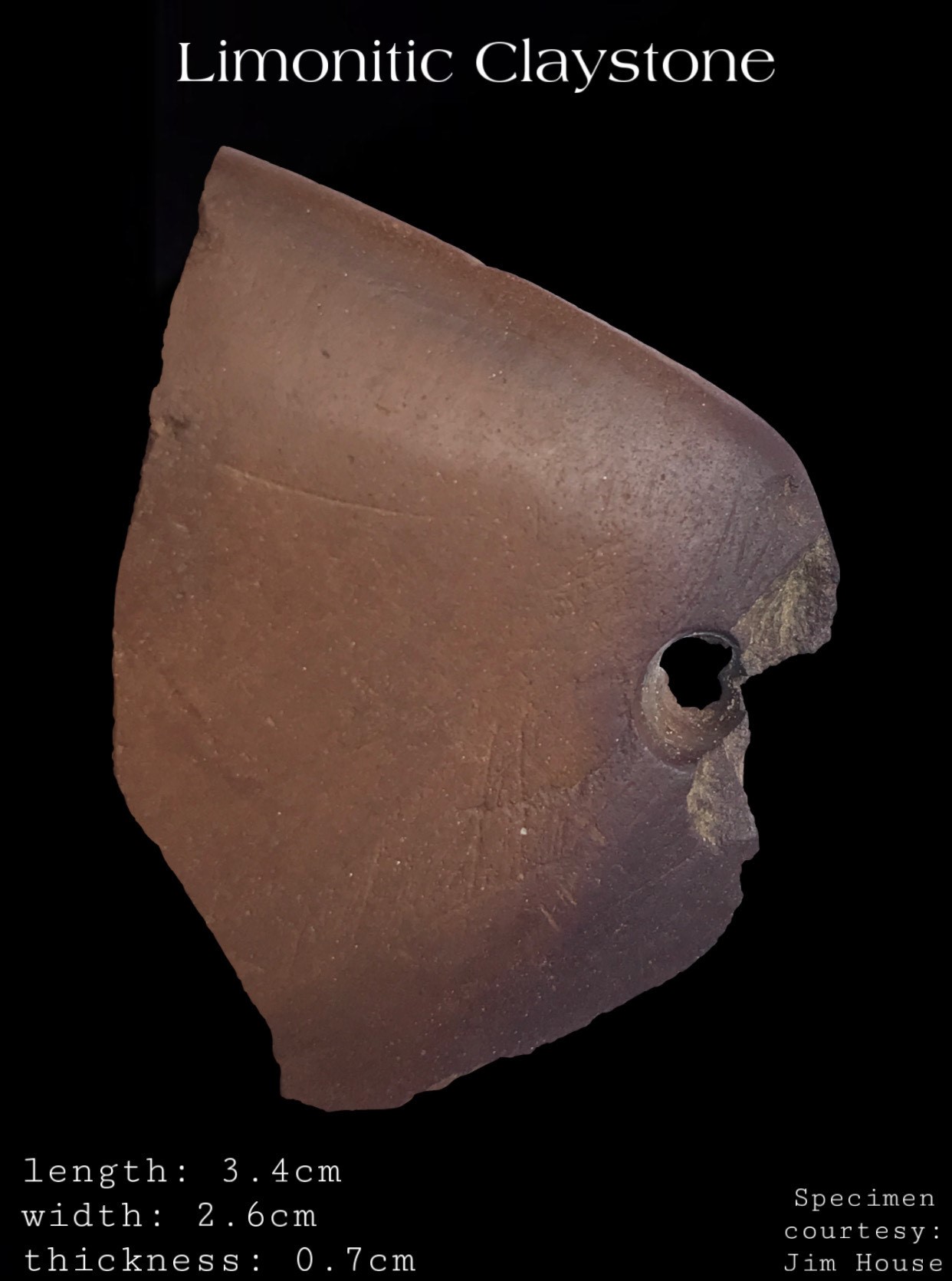

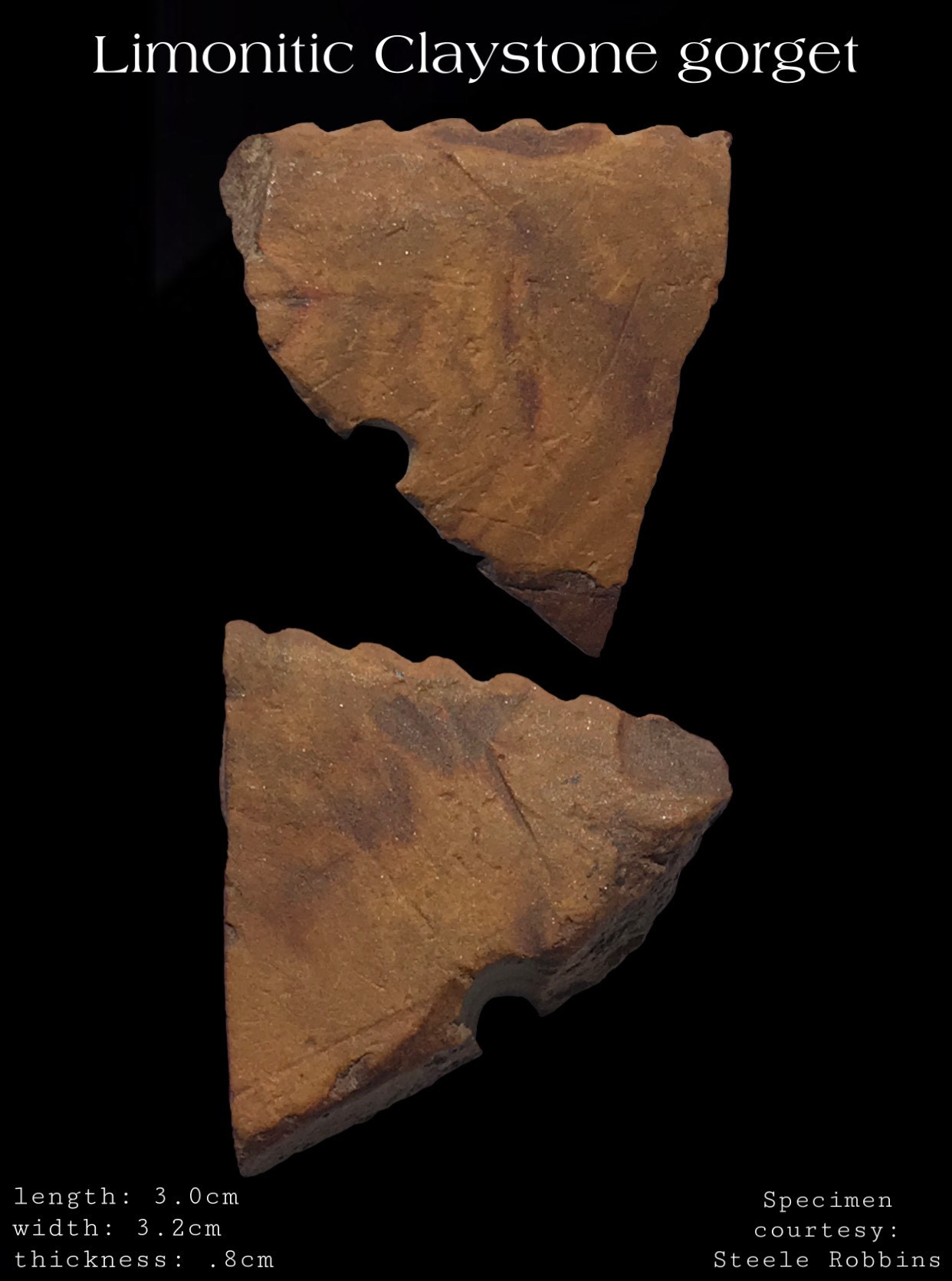

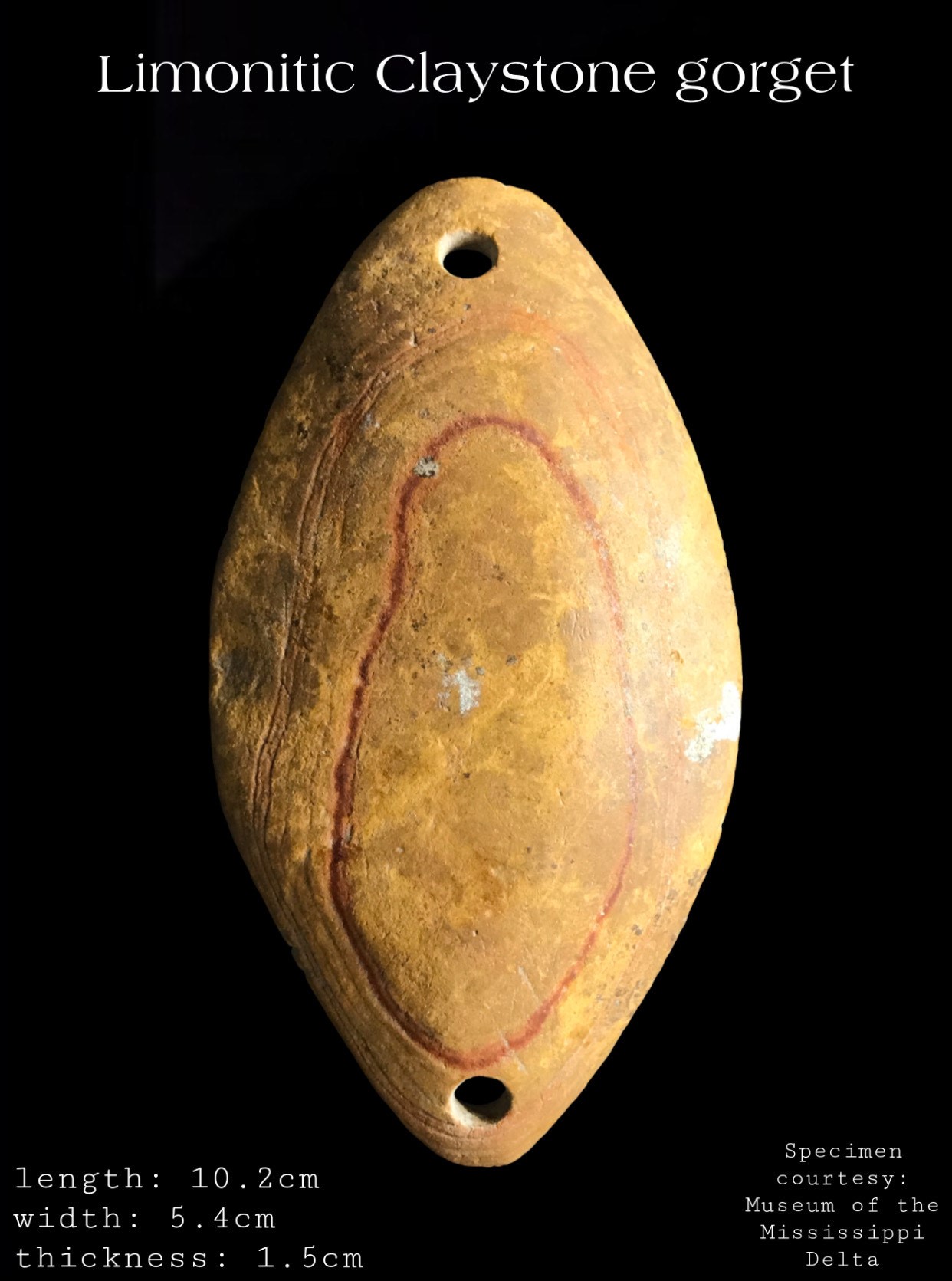

Limonite

Limonitic claystone is a common natural occurrence in the weathered zone throughout much of Mississippi’s coastal plain geology. It typically occurs at the contact between beds of sand and clay, as mineral-rich groundwater moves through the sand beds and infiltrates the adjacent clay beds. Tiny clay particles in the clay beds are cemented together by iron-oxide/hydroxide precipitated from the groundwater, forming limonite. Because of the varying bedrock chemistry and iron content of the water, limonitic claystones can differ highly in color from tan, brown, red, orange, pink, and purple. Darker colors such as black and purple occur due to a manganese oxide called pyrolusite also being present. Differences in color can also highlight the finely laminated sedimentary layers in the stone. Layers with a higher silt content have more pore-space for limonite to deposit and can appear darker in color. Mineralized layers of limonitic claystone are typically more resistant to erosion than other unmineralized layers in the surrounding geology. Therefore, they are readily accessible as indurated ledges along stream channels, along valley-walls, and on hillsides/tops in various terrains of the eroding bedrock. Limonitic claystones were a natural resource highly utilized by Mississippi’s Indigenous peoples. It could be ground for ochre or easily carved for use as implements, tools, or ornaments.

Siderite

Siderite is an iron carbonate mineral that forms in a variety of environments in Mississippi. It is reddish-brown to black and forms as nodules of various shapes and sizes. It is typically much harder than limonitic claystone, can easily be polished, and has a flaky weathering character. Siderite nodules can be found in many of the geologic formations of Mississippi. It is best known for its abundance in Mississippi River gravels and from the muddy brackish water environments along the shores of Mississippi’s Gulf Coast.

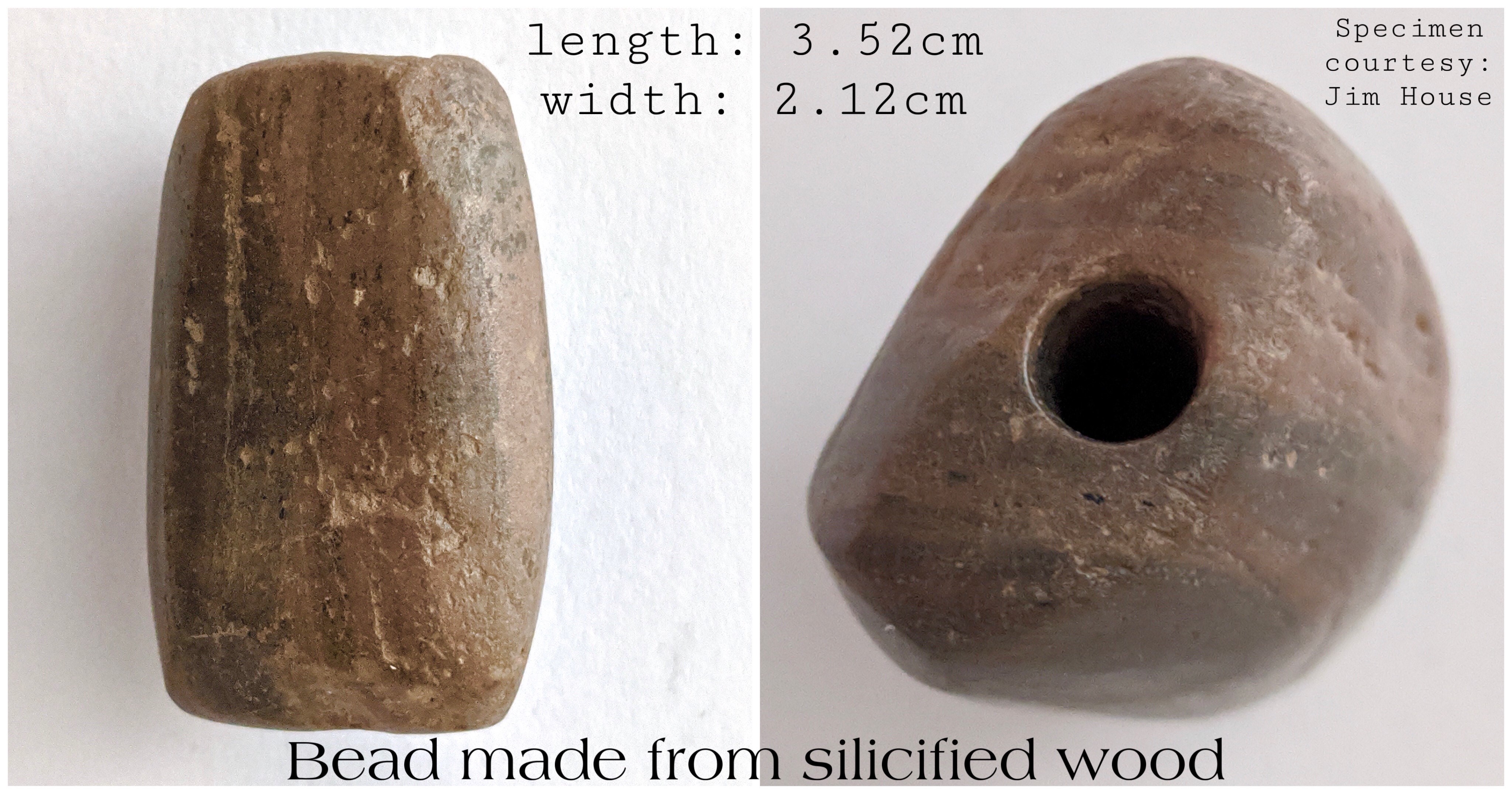

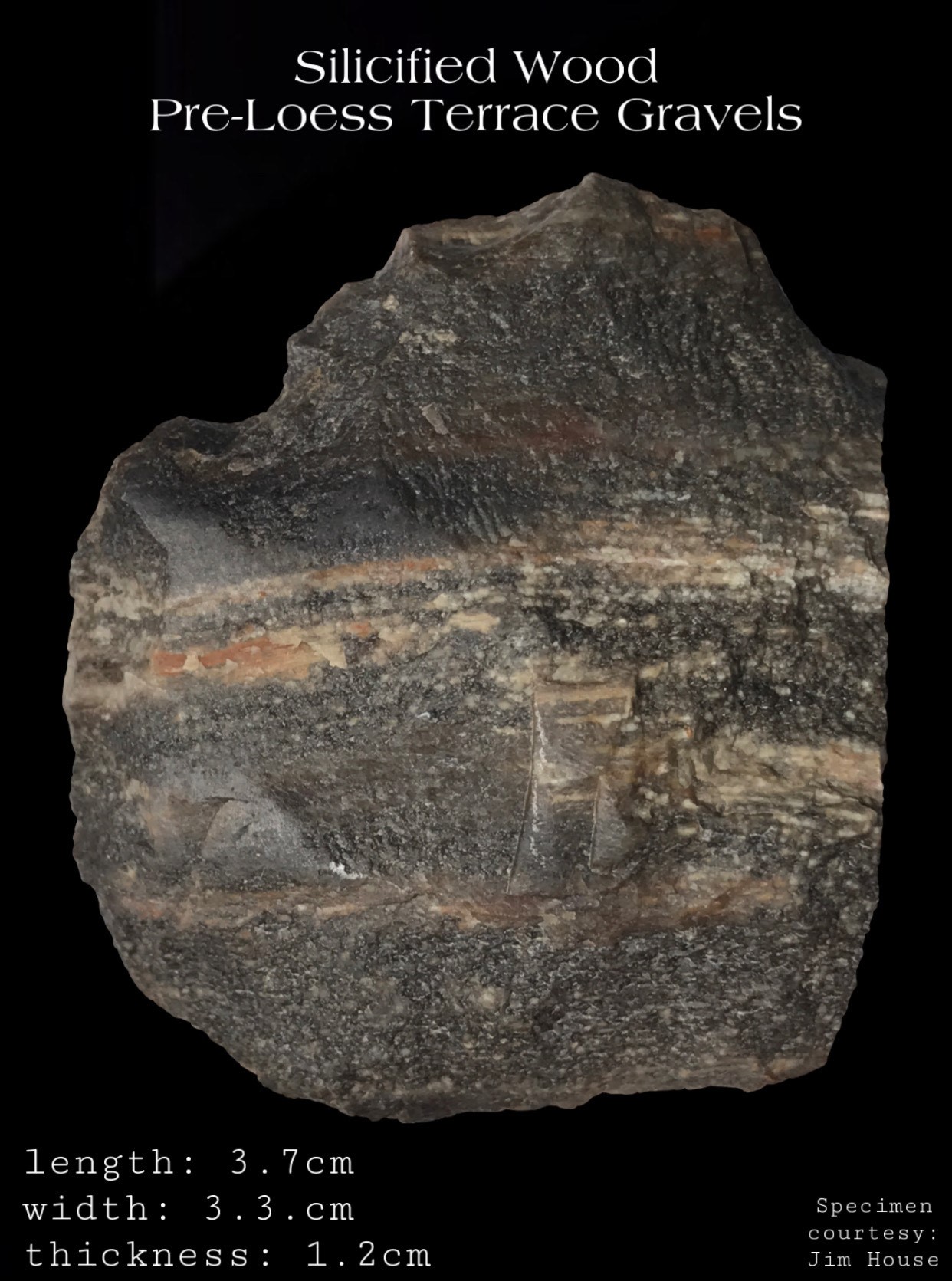

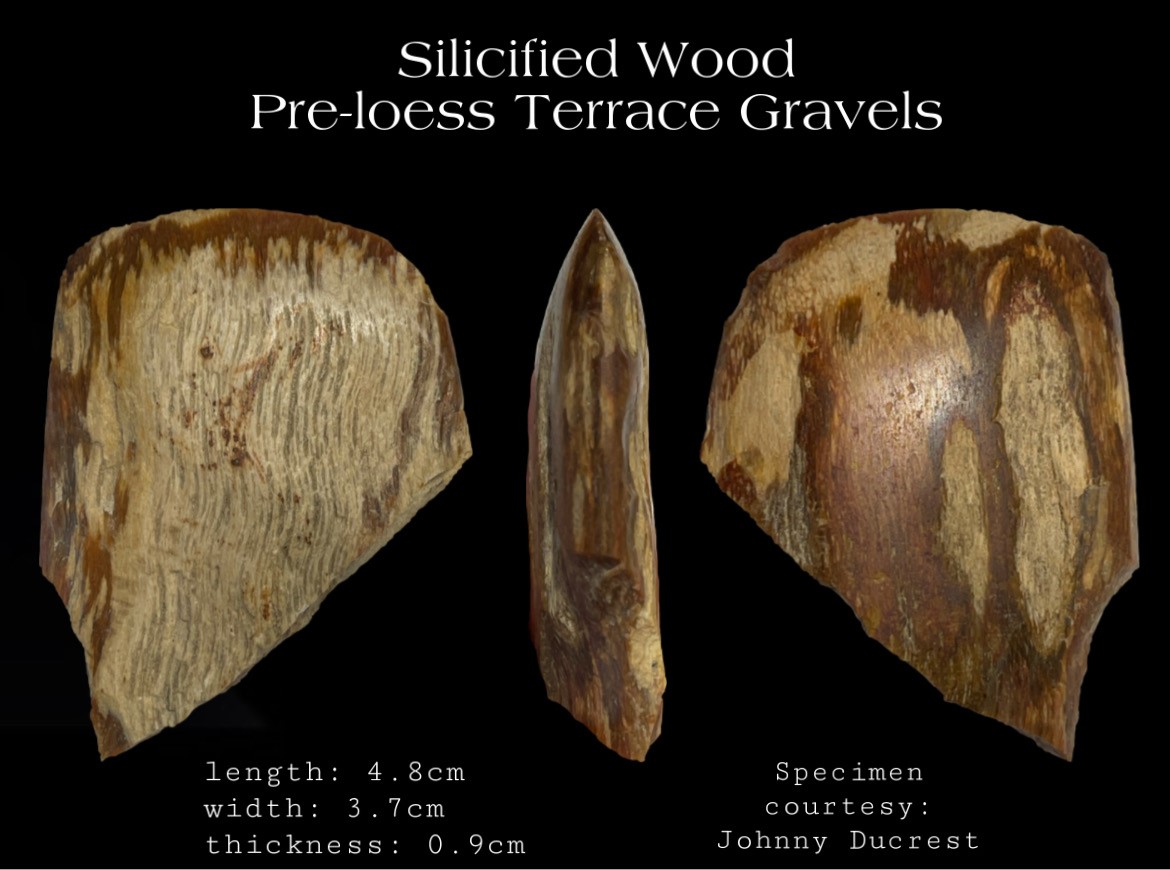

Petrified Wood

Most of the geologic formations, terraces, and alluvial deposits in Mississippi contain petrified wood of varying quality. It is often exposed through erosion and concentrated in stream and river channels. Petrified wood ranges from brittle to chert-like. Higher quality petrified wood contains significant chalcedony replacement. Petrified wood was often utilized to some degree where it was abundantly available and especially where other suitable rock materials were scarce. It is identified from to the wood grain texture and is preserved through a process of silica replacement called permineralization. Petrified wood has been identified on pre-historic archaeological sites throughout Mississippi.

Fossil Palm (Palmoxylon) is a distinctive type of plant fossil easily distinguished from petrified wood by its straw-like structures. Chalcedony replaced fossil palm is a relatively high-quality lithic resource. Fossil Palm can be translucent to opaque and is typically yellow-orange but can vary highly in color. It is typically derived from Oligocene-age strata of the Forest Hill and Catahoula Formations in Southwest Mississippi but also occurs in the Tallahatta Formation of East-Central Mississippi.

References: Mississippi Geology 10,1; Mississippi Geology 2,4; Mississippi Geology 4,2; Mississippi Geology 11,2; Mississippi Geology 2,2; Mississippi Geology 9,3

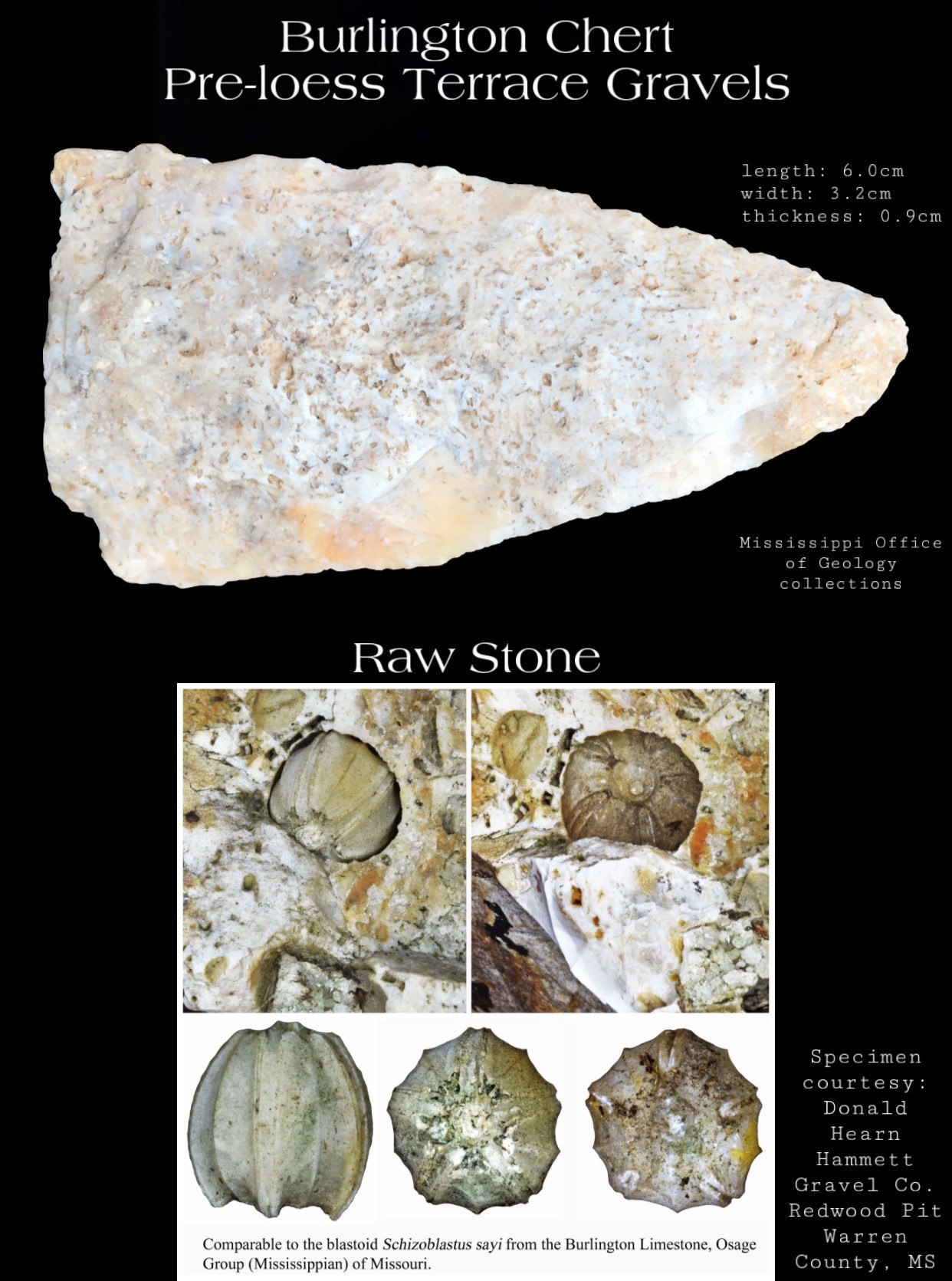

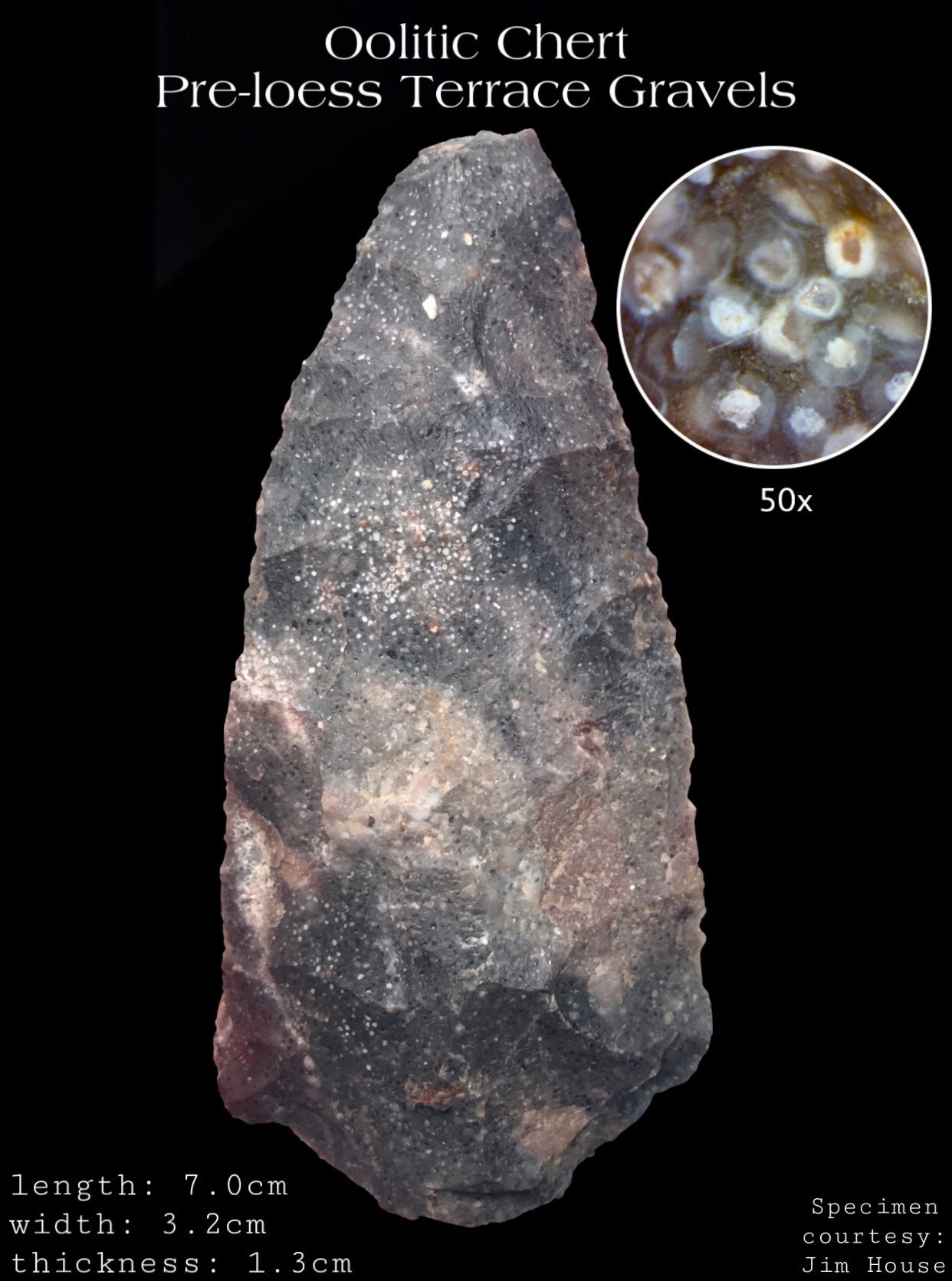

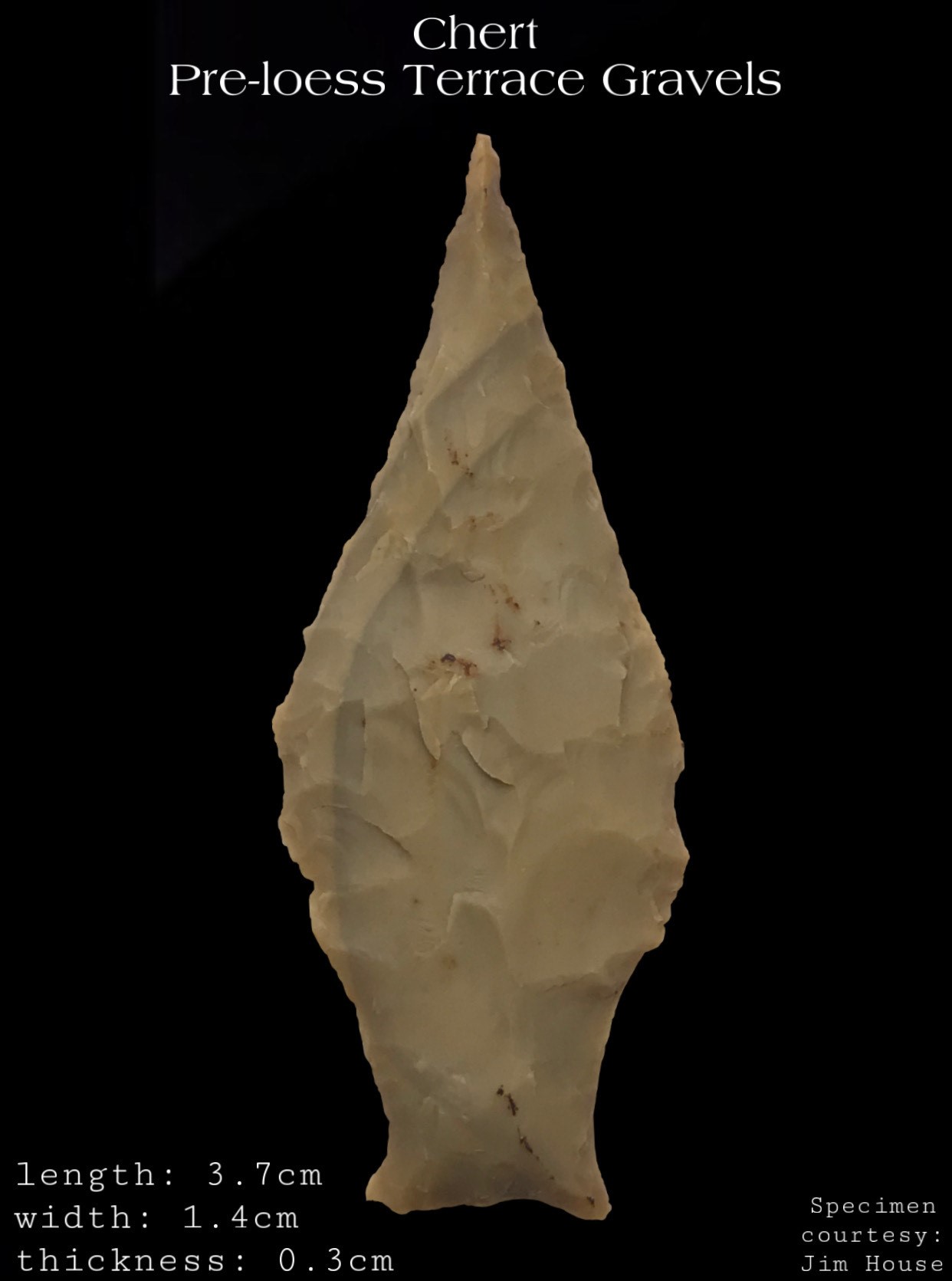

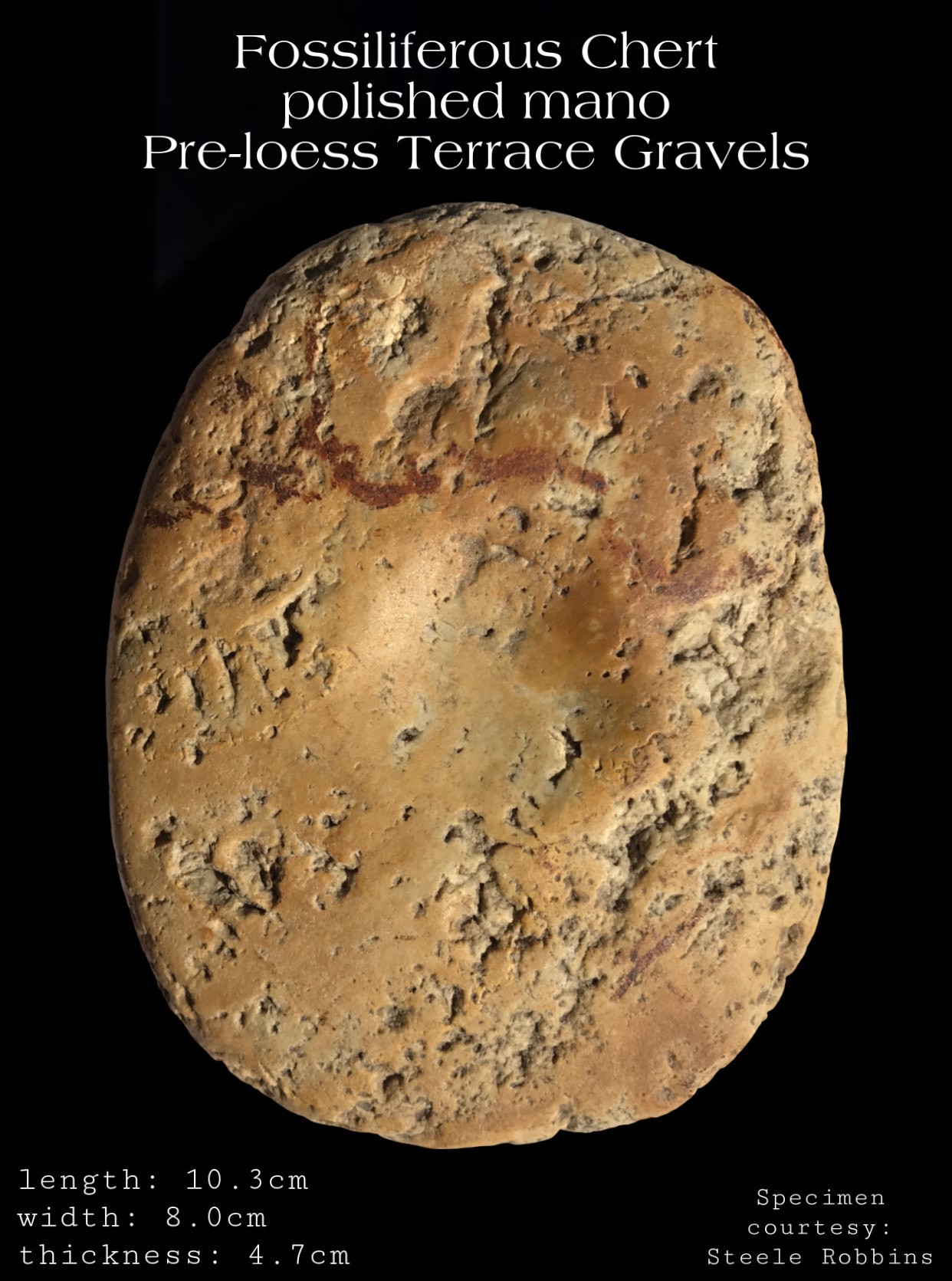

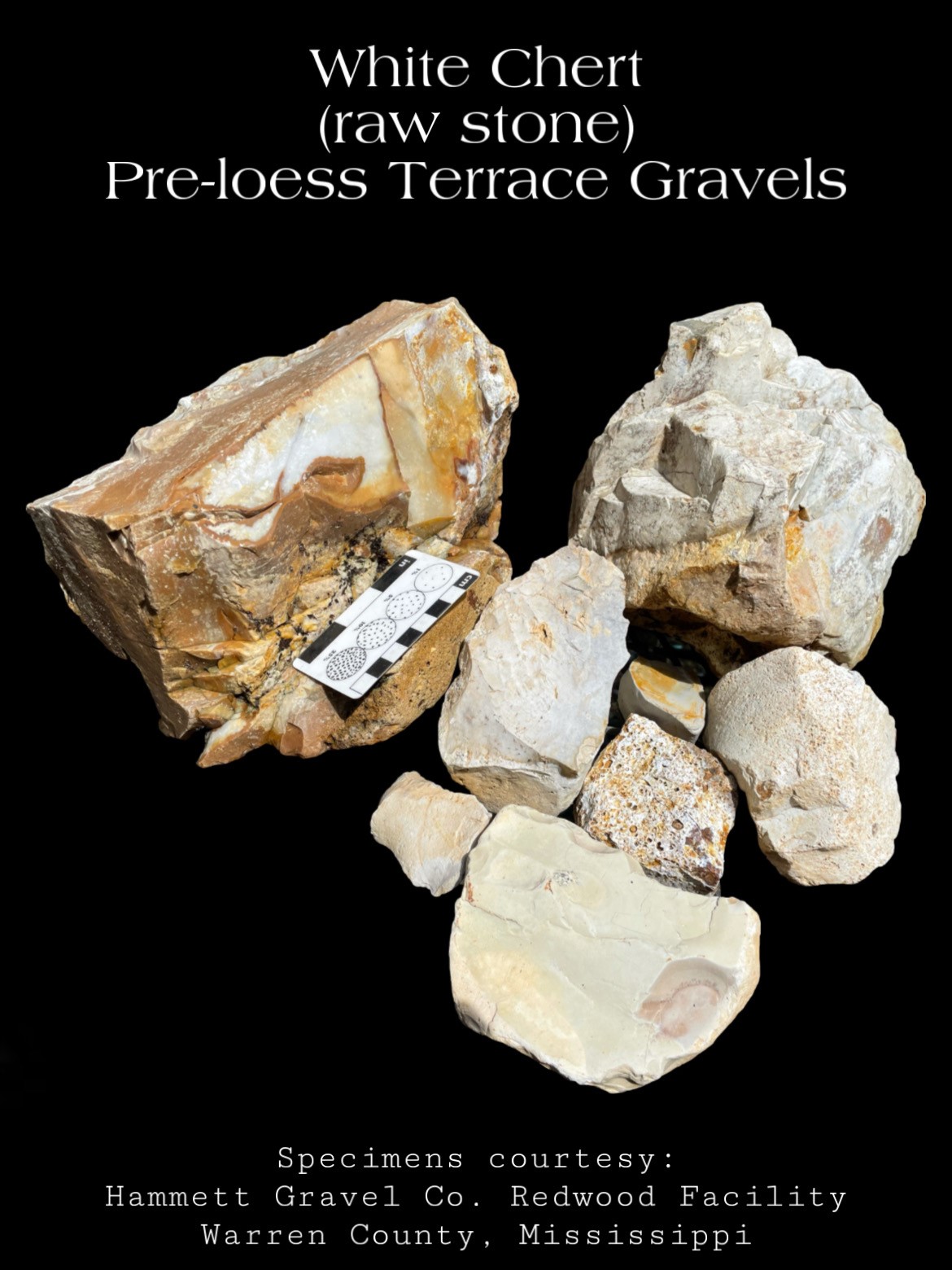

Pre-loess Terrace Deposits

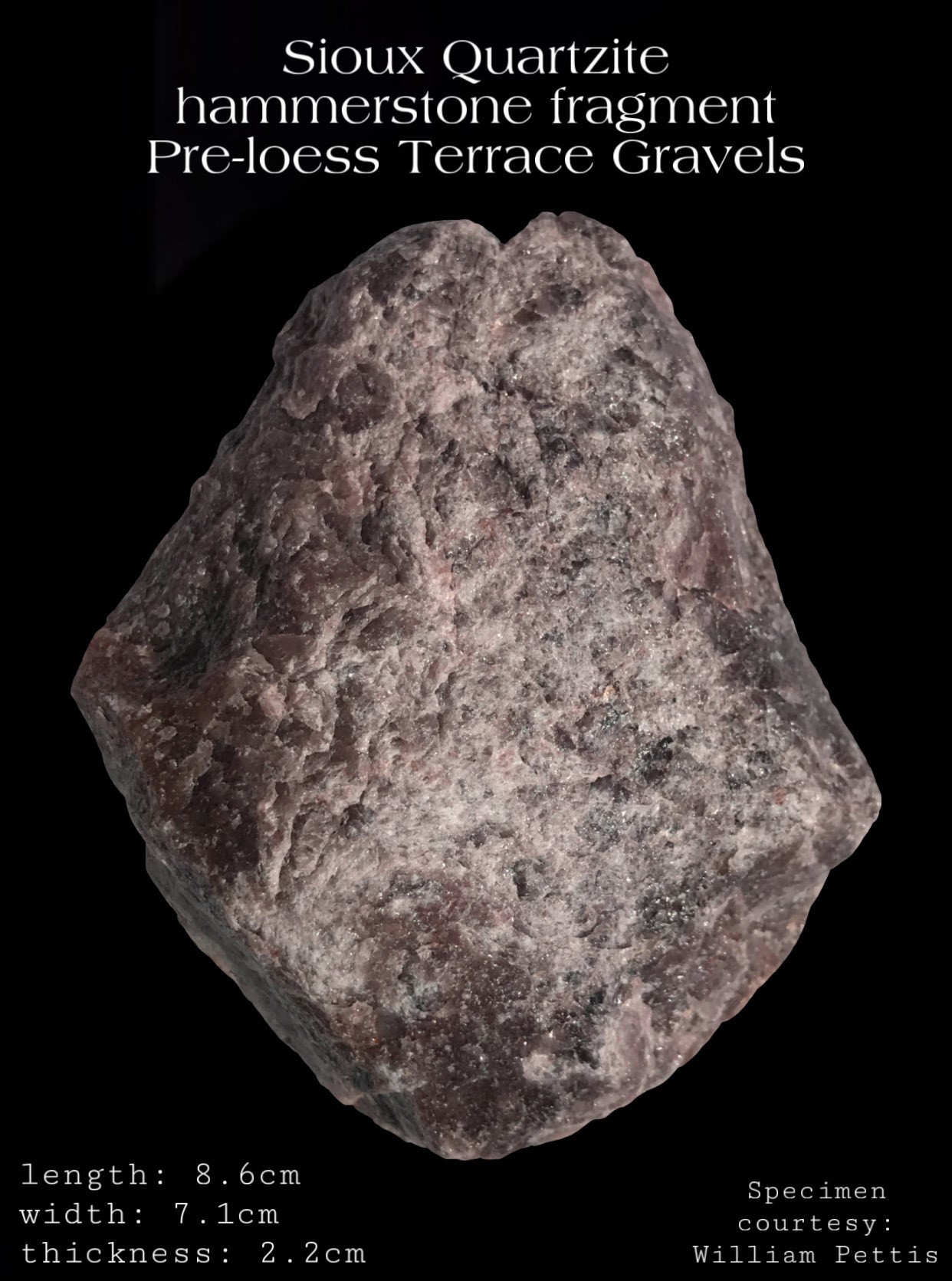

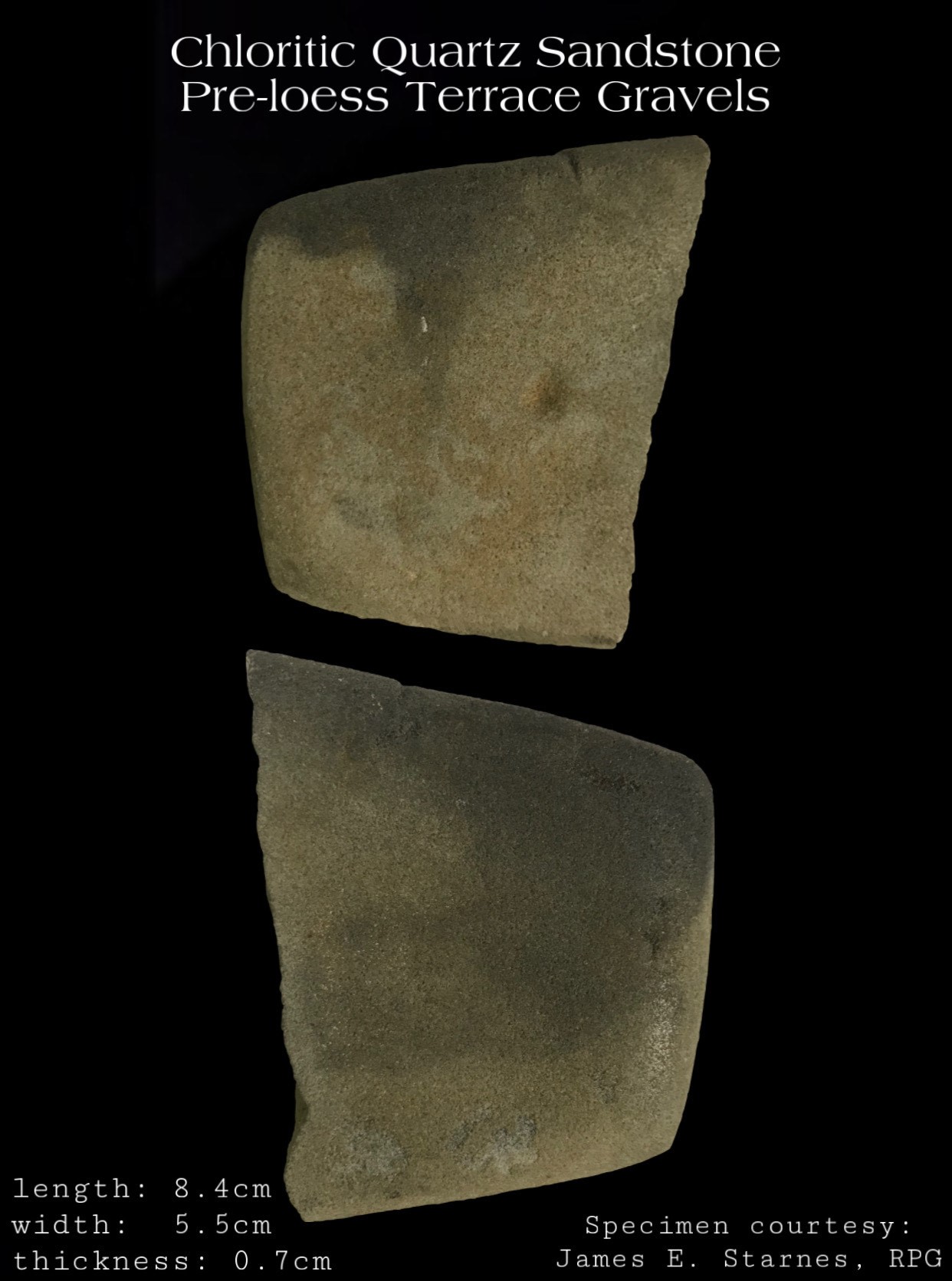

Pre-loess Terrace gravels can be found in the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain and are largely masked by thick deposits of loess from the late Pleistocene. These mid-Pleistocene age terrace deposits parallel the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain from Desoto to Wilkinson County, Mississippi and are equivalent to the gravel deposits along the southern part of Crowley’s Ridge. Previous literature also misattributes Pre-loess Terrace Deposits to the “Citronelle Formation.” Pre-loess Terrace gravel contains clasts of higher quality and sizes many times larger than those of the High Terrace gravel. Pre-loess Terrace gravels are predominantly chert, derived from similar regions of the Paleozoic limestone bedrock drained by the Mississippi River’s present-day watershed. Pre-loess gravel also includes distinct varieties of rock types that are associated with the evolution of the ancestral Mississippi River during glaciation. These deposits include gravel to boulder size clasts of chert, St. Francis Mountain rhyolites, Sioux Quartzite, geodes from the Keokuk region, Missouri Lace Agate, large cobble size quartz clasts, a variety of sandstone and quartzite, and various types of jasper. Pre-loess Terrace gravel also occur re-deposited in stream terraces and alluvium from streams that dissect the Loess Bluffs Region.

References: Claiborne County Bulletin; Hinds County Bulletin; Rocks and Fossils Found in Mississippi’s Gravel Deposits

Sioux Quartzite

Sioux Quartzite is a distinctive Precambrian metaquartzite found in the ancestral Mississippi River Pre-loess Terrace gravels. The bedrock source region for Sioux Quartzite is in South Dakota and southwestern Minnesota. Sioux Quartzite in the Pre-loess Terrace gravels is transported from mid-Pleistocene glacial age outwash. It is the dominant clast in “Kansan” glacial moraines bordering the Missouri River. Prior to Pleistocene glaciation, the Missouri River once flowed north, draining the western interior into Hudson Bay. The presence of Sioux Quartzite in Mississippi marks the time when the Missouri River was blocked by advancing glacial ice and forced southward into the Mississippi River Valley. Sioux Quartzite is a hard, pink to dark purple, often banded quartzite. It is fine to coarse-grained and may contain quartz gravel inclusions and, in rarer cases, can be brecciated. The quartzite can be found as cobble to boulder-sized clasts where it has been reworked into stream alluvium. It is highly metamorphosed which greatly inhibits its knappability, as it renders an irregular to sub-conchoidal fracture. It was extensively utilized as a hardstone and was peck and ground and polished into beautiful tools and ornaments. Its superior durability and commonly large clast size make it an ideal hammerstone material. It was preferred for use in quarrying Hattiesburg Quartzite in Franklin and Amite counties, Mississippi as evidenced by numerous broken fragments of Sioux Quartzite hammerstones at heavily worked outcrops at quarry sites.

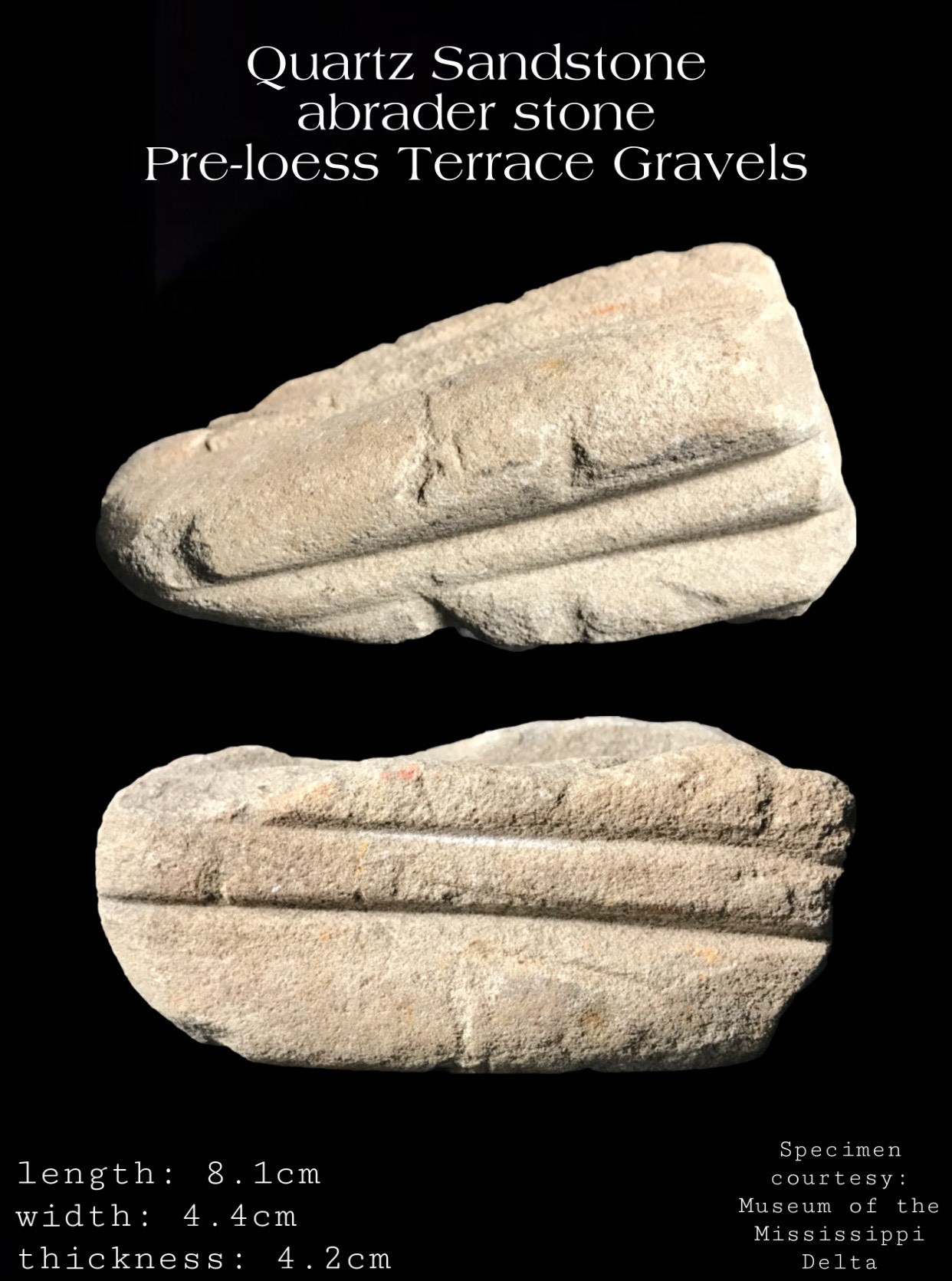

Quartz Sandstone

Quartz sandstone is a common and often large cobble to boulder-size clast component in Pre-loess Terrace Gravels. These sandstones are often white to grey and have a sparkling appearance to them due to cementation by quartz overgrowths. Some varieties are feldspathic, and some are green from the presence of the mineral chlorite. Quartz veins are also common in clasts of Pre-loess Terrace sandstone.

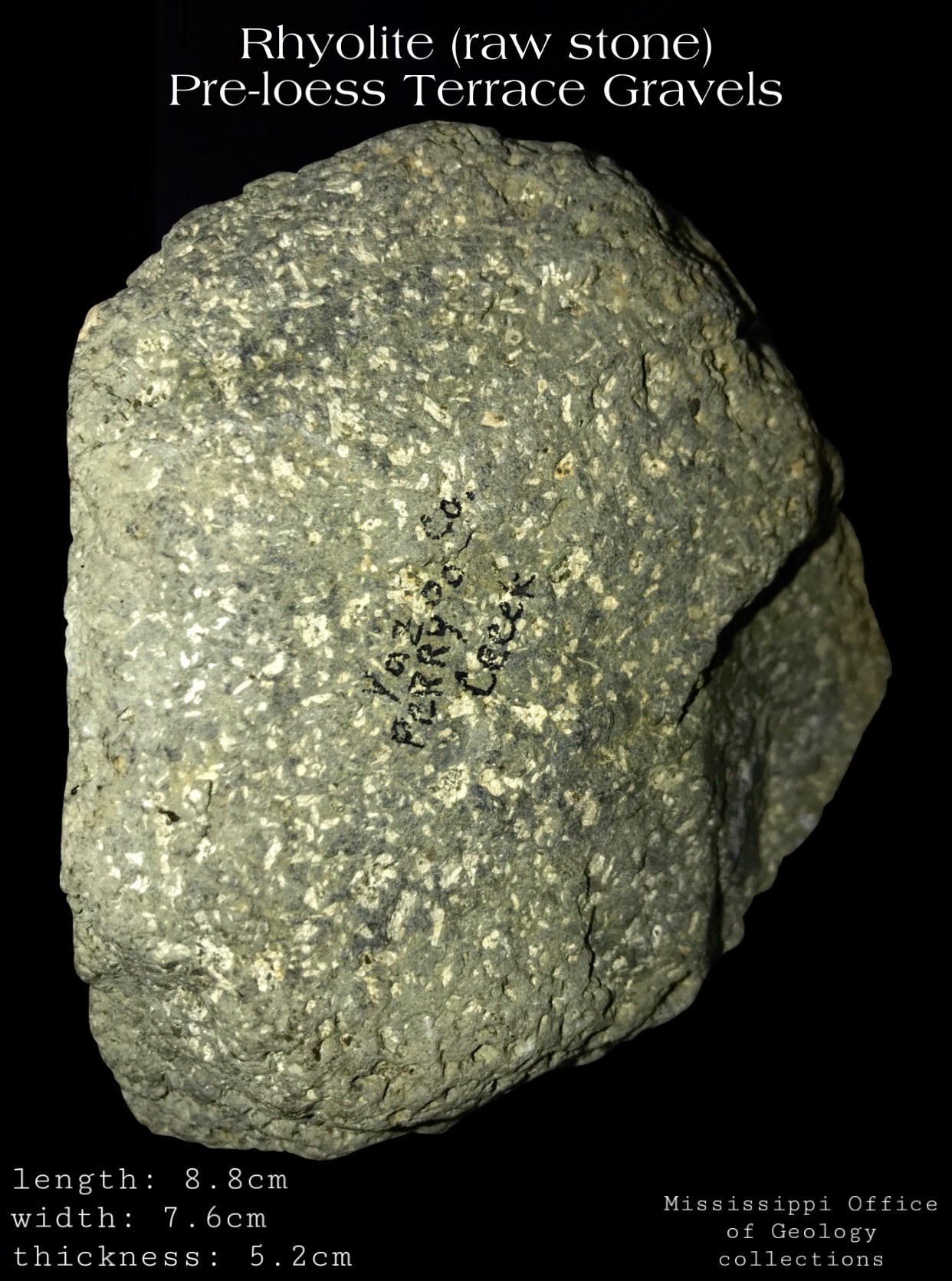

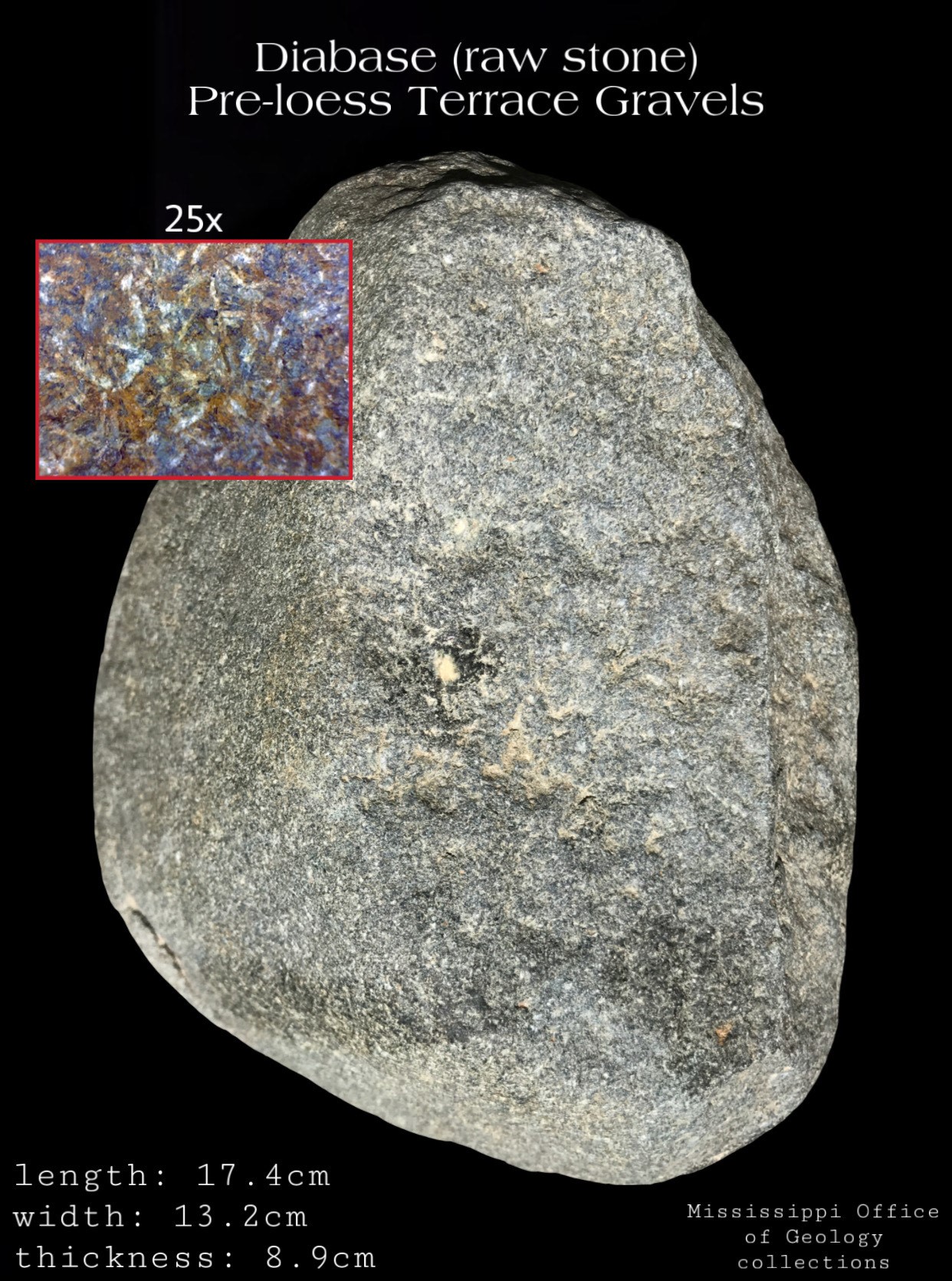

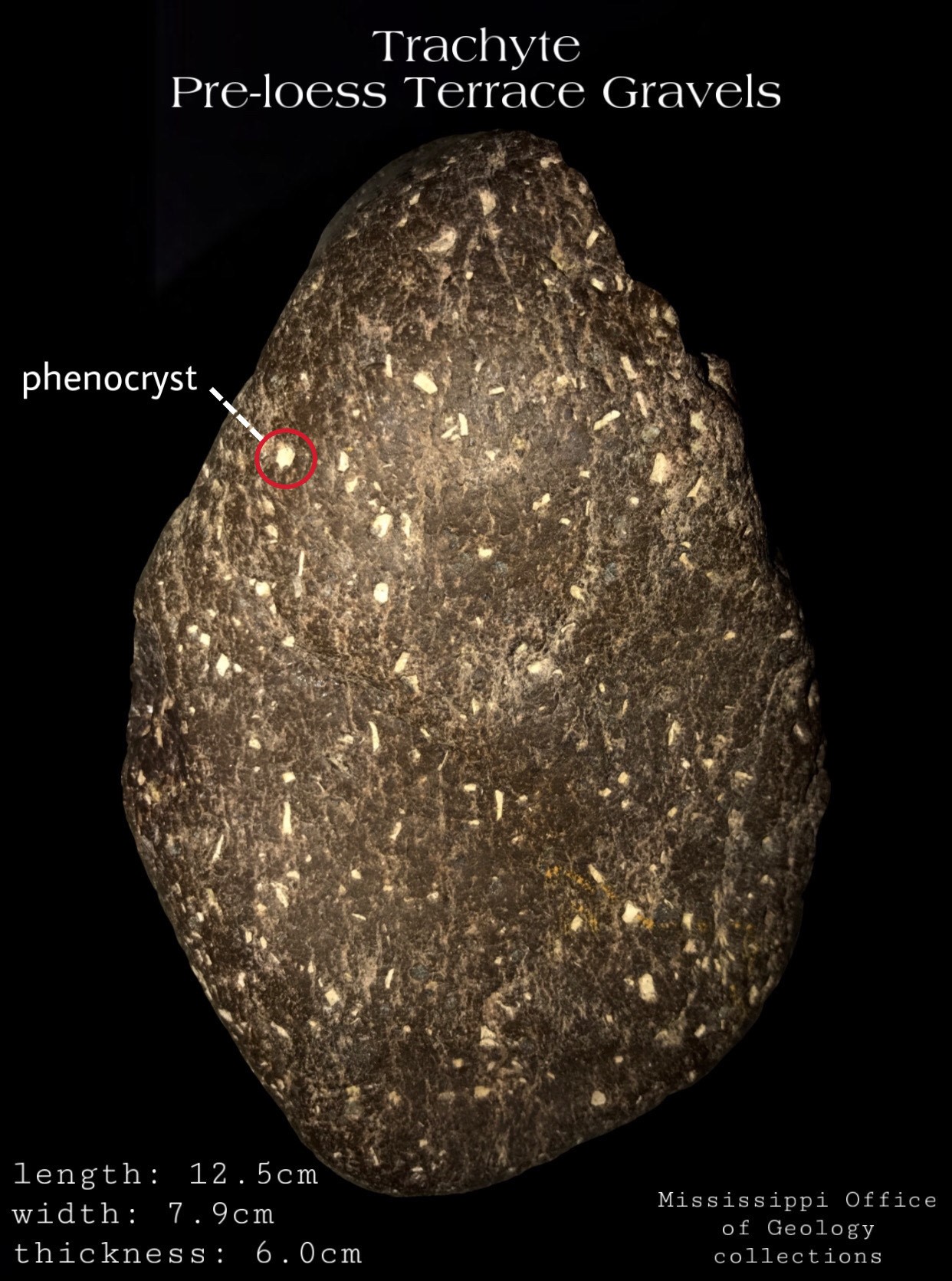

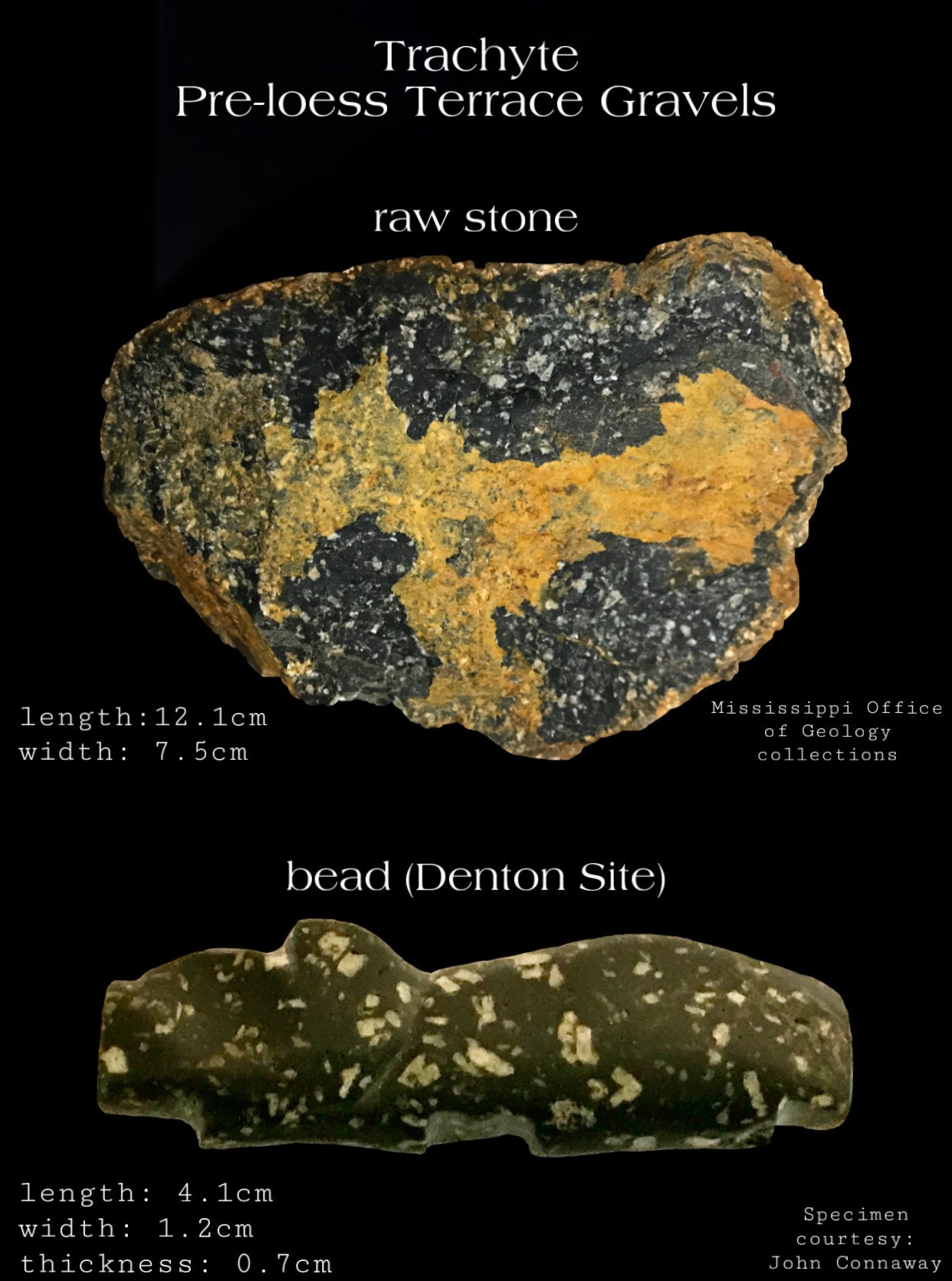

Igneous Rocks

The closest exposure of bedrock sources for igneous rocks from Mississippi is the ancient volcanic complex of the St. Francois Mountains in southeastern Missouri. During mid-Pleistocene Kansan glaciation, glaciers plowed through Missouri. Meltwaters and ice-dam breaks carried a flood of igneous rocks from the St. Francois region down the ancestral Mississippi River. St. Francois igneous rocks that occur in the Pre-loess Terrace gravels are rhyolite, trachyte, welded tuff, and significantly less common diabase. Pre-historic cultures widely exploited the igneous materials from the bedrock of Missouri’s St. Francois region and widely traded the material throughout the mid-continent and across the southeast. Much of the exotic igneous material from the St. Francois region that can be found as artifacts on indigenous archaeological sites in Mississippi could have been traded from the original bedrock sources. Though, identical material readily available in the Loess Bluff region was undoubtedly exploited. The availability of these resources complicates the understanding of trade in the archaeological record and causes a significant problem interpreting sites in Mississippi with artifacts made from resources of St. Francois igneous materials.

Jasper

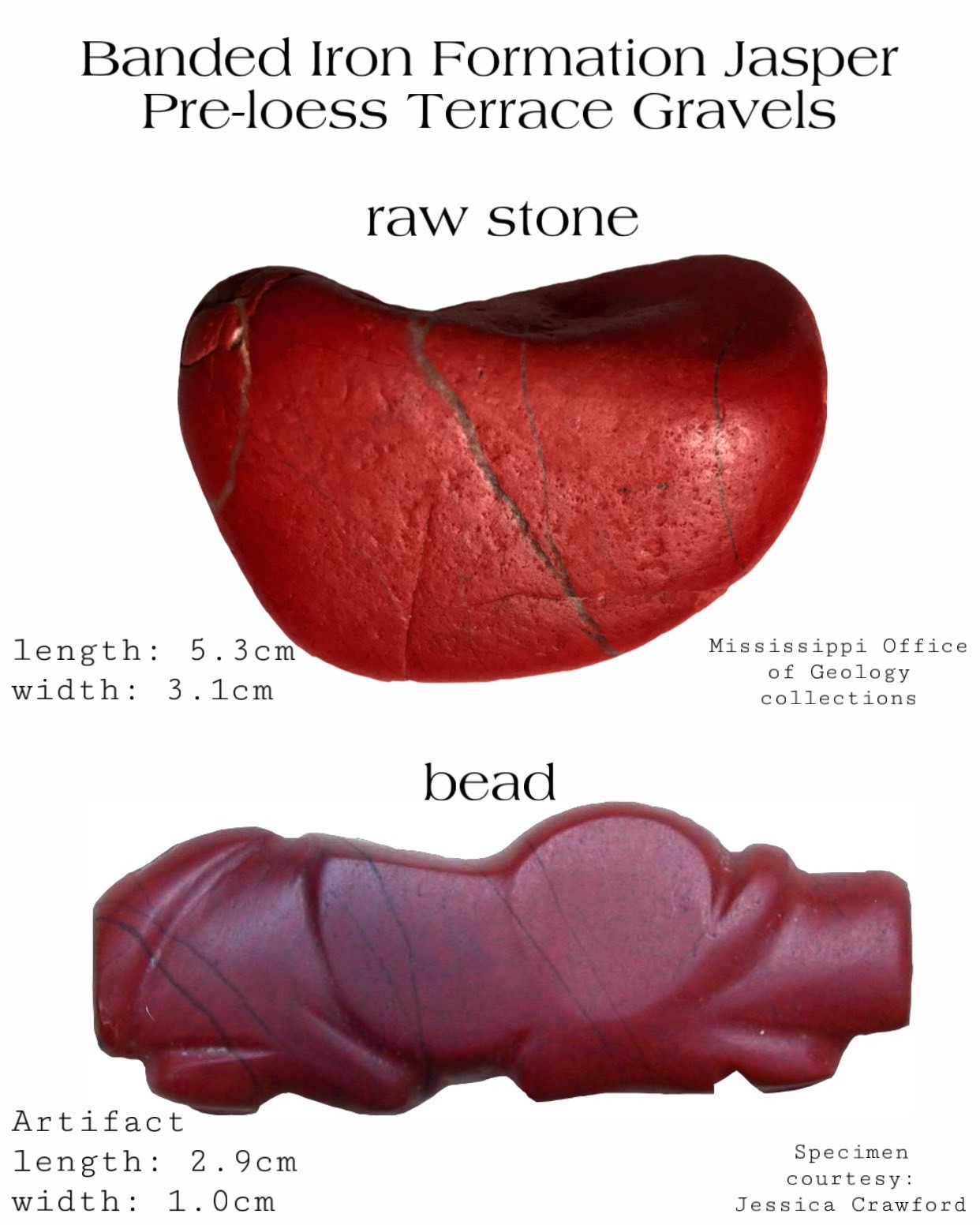

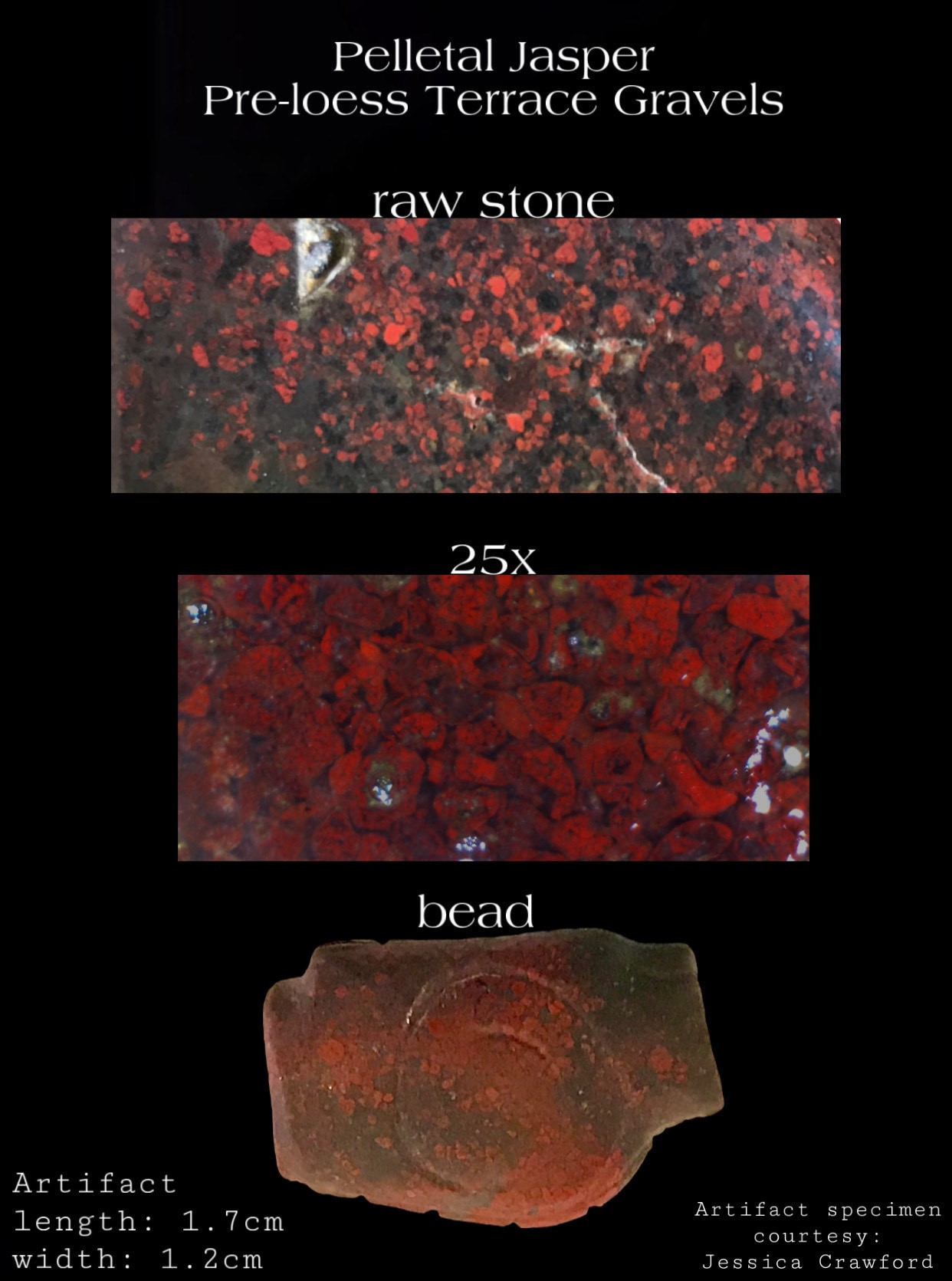

Jaspers are chert varieties valued for their color. Jasper can range in color from red to brown or green and owe their color to iron impurities. These high-quality jaspers from Pre-loess Terrace gravel were utilized primarily in the Native American lapidary industry. This renaissance of the lapidary industry occurred in the lower Mississippi Valley throughout the Middle and Late Archaic cultural periods. Jaspers are known from several different chert types, each with a variety of textures and physical properties. Most jaspers are common varieties of chert, but other varieties were more important to this industry.

Pelletal Jaspers are chert-replacement of iron-rich pelletal carbonate mudstones that were formed in tropical near-shore marine environments. Two types of pelletal jasper derived from Paleozoic bedrock are widely available in the Pre-loess Terrace gravels along the bluff line and as a constituent in the Mississippi River gravels. First, green jasper is from iron formed in a reduced state. Second, red jasper is from iron in an oxidized state. While both are common constituents in local gravel resources, the red-colored variety is more common than the green-colored variety. Gravel clasts of pelletal jasper can range in size from small pebbles to large cobble specimens. The softer, banded-iron formation jaspers that originate from bedrock much further north in the Mississippi River’s watershed are abundantly available within local gravel resources and were similarly utilized.

Banded Iron Formation jasper are also common in Pre-loess Terrace and Mississippi River gravels. These jaspers are quite softer and easier to work than other available jasper varieties. This jasper type is typically brick red in color, while a rare green variety has also been noted. It typically exhibits finely laminated layering that may also alternate in color. Fine quartz veins may also crisscross the stone. It has a matte luster on fresh fracture but can also be polished as a natural occurrence and as an artifact.

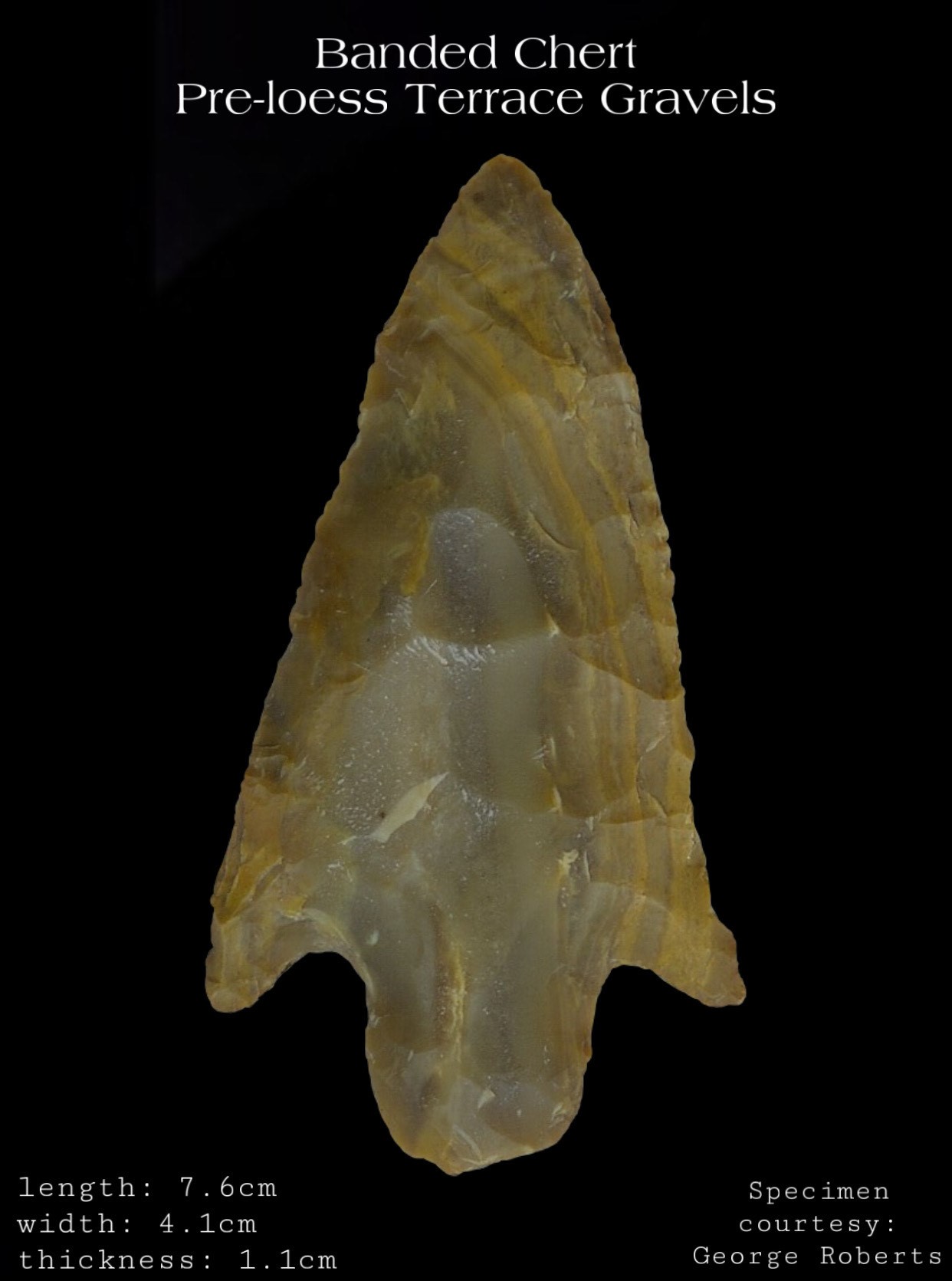

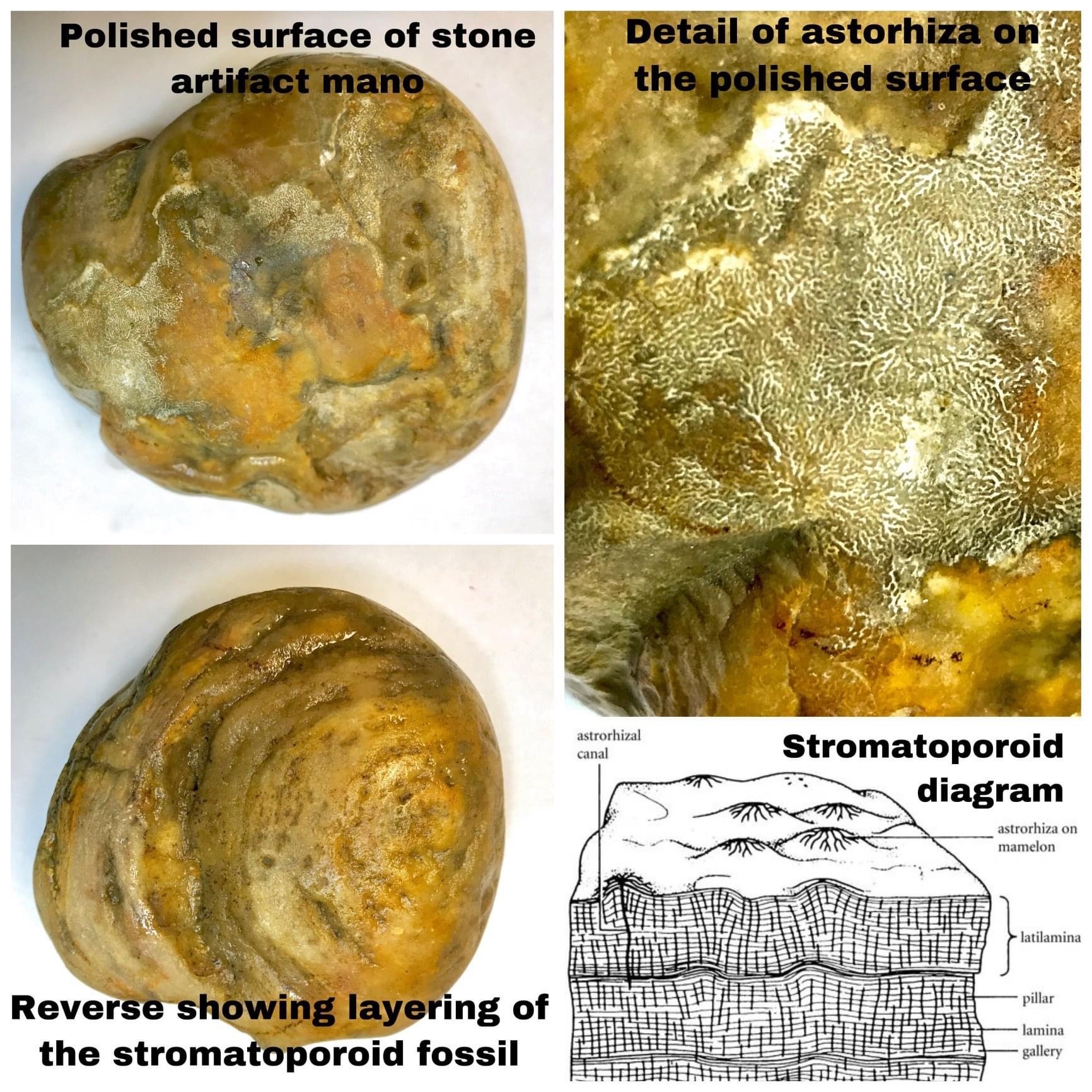

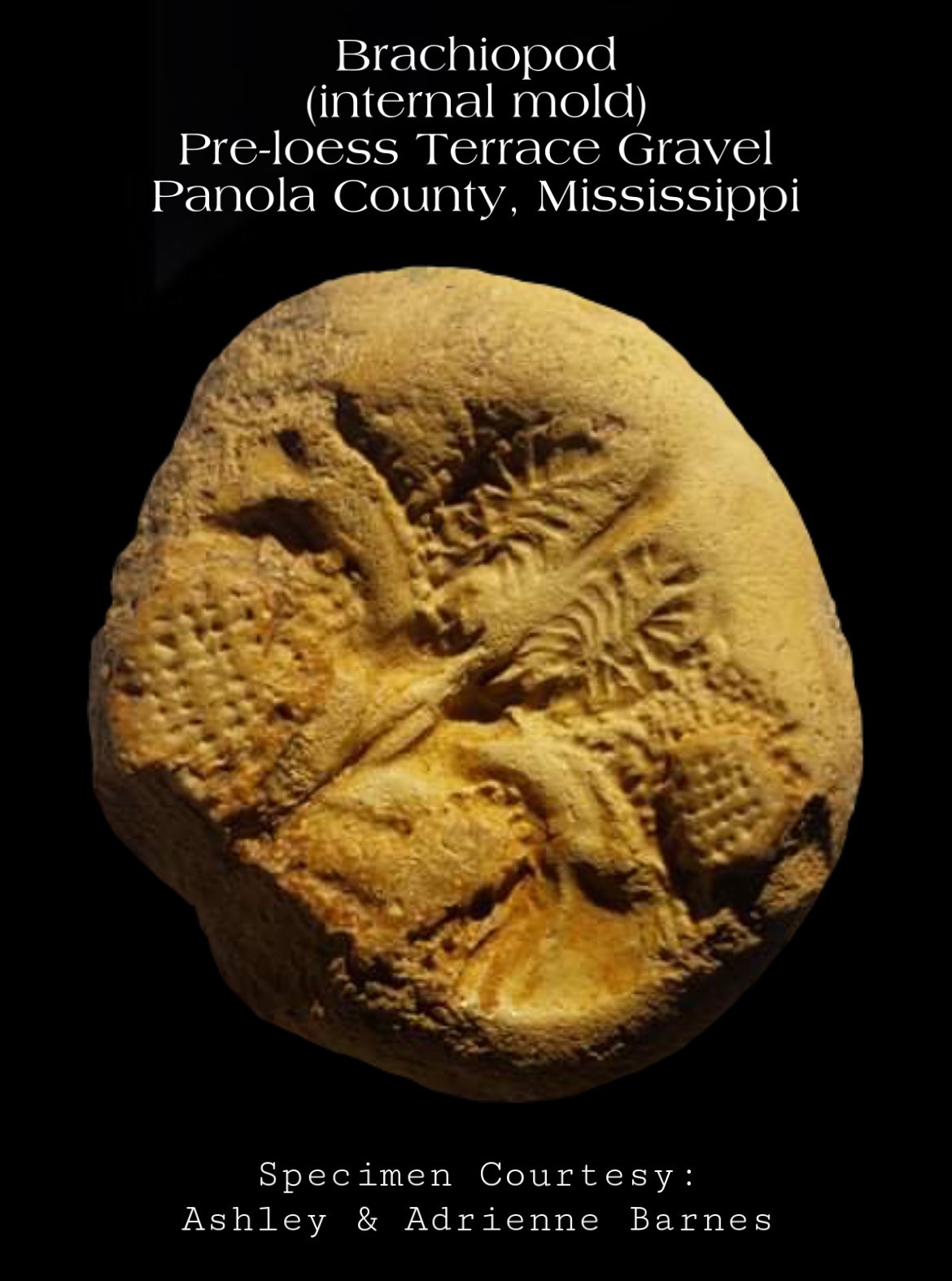

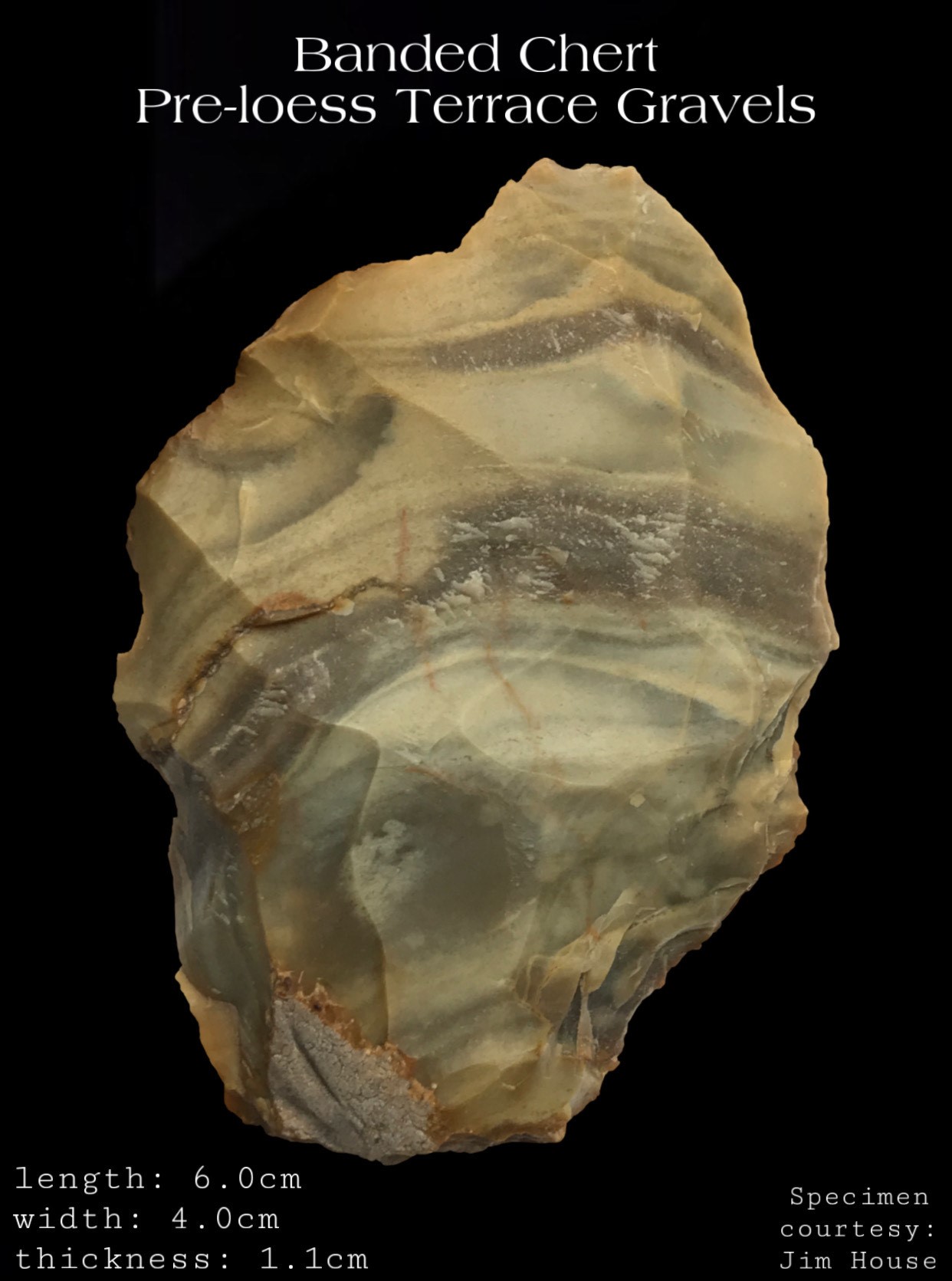

Chert

A wide variety of typically high-quality chert occur in the gravels of the Pre-loess Terraces. These gravels can be translucent to opaque and range in color from brown, tan, grey, blue-grey, white, pink, red, and orange. Banded and chalcedony-rich varieties are very common. These gravels are often fossiliferous, containing the invertebrate remains of crinoids, corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, and stromatoporoids. They also can exhibit a wide variety of sedimentary structures such as oolites, carbonate sands, and bedding structures. Due to the glacial history of these gravel deposits, the cortex varies from highly weathered to even absent, and clast size can include ice-rafted boulders weighing well over a ton. Some chert varieties in Pre-loess Terrace gravel, such as Burlington and Pitkin, can be directly attributed to their original bedrock source due to their appearance and fossil content. Many of these gravels may be indistinguishable from material traded from the original outcrop regions in an archeological context.

Mississippi River Alluvium Gravels

Gravel bars along the Mississippi River contain a suite of pebble-to-large cobble-sized clasts of various materials from mid-continent bedrock sources within the river’s watershed. Paleozoic chert gravel is most of the available rock material. There is a significant increase in variety and frequency in the component of igneous rocks as compared to the ancestral Mississippi River Pre-loess Terrace Gravels of the western Loess Bluff Region, particularly the presence of Canadian granite. Also, there is the presence of a diverse suite of metamorphic rocks along with Lake Superior Agate that are absent from the Pre-loess Terraces. The presence of these rocks marks further shifts in source material during the last glacial advance and retreat, establishing the new Mississippi River’s basin headwaters.

References: 1:100,000 Greenwood Geologic Map; Rocks and Fossils Found in Mississippi’s Gravel Deposits

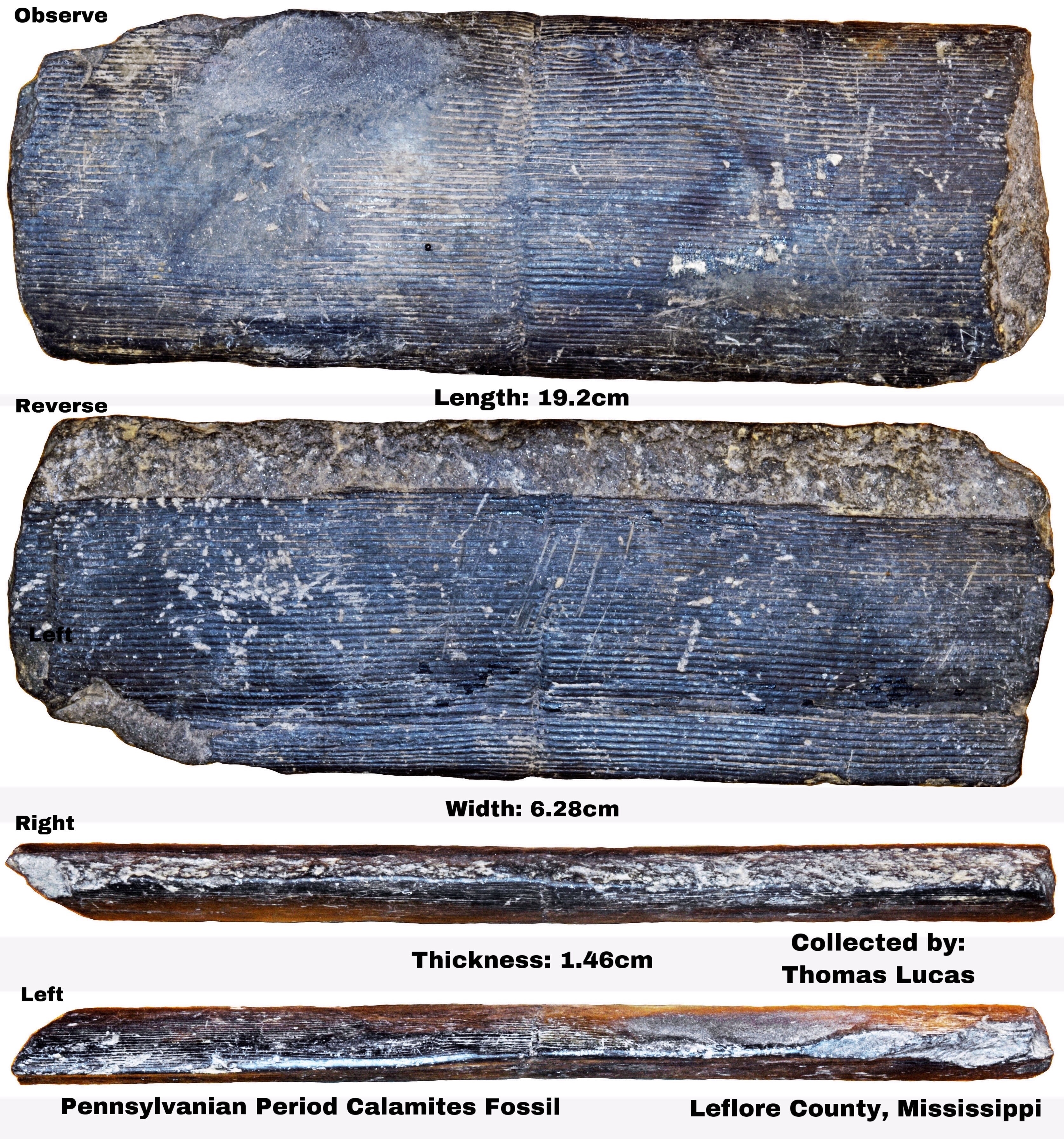

Cannel Coal

Cannel coal is a type of bituminous coal more accurately classified as a grade of carbonaceous shale. This black claystone is considerably durable compared to other types of coal. It has been exploited worldwide throughout antiquity for both its ease in carving and in maintaining a black, highly polished surface. In North America, cannel coal comes from Carboniferous age bedrock deposits that are dominated by fossil plant remains of Lepidodendron and Calamities. The Mississippi River and its northern tributaries drain this Paleozoic bedrock region; therefore, cannel coal can commonly be found as a resource in the Mississippi River gravels. Cannel coal’s utilization by prehistoric Native American cultures is evidenced by stunning artwork and some unusual utilitarian artifacts found in Mississippi.

Mississippi River Chert Gravel

Chert gravels along the Mississippi River contain a similar suite to that of the Pre-loess Terrace gravels but likely do not include the extreme clast sizes found in the Pre-loess Terraces. Mississippi River gravels are also comprised of distinctly more water-worn cobbles that tend to exhibit a greater thickness of cortex on average than chert in the Pre-loess Terraces.

Mississippi River Igneous Rocks

Igneous rocks from Mississippi River gravels differ in both variation and abundance from those found in the Pre-loess Terrace gravels. Mississippi River gravels contain an abundance of granite, syenite, and basalt in addition to the St. Francois igneous rocks in the Pre-loess Terrace gravels.

Mississippi River Metamorphic Rocks

Sioux Quartzite is not nearly as common in Mississippi River Gravels and is more often represented by smaller clasts when compared to the Sioux Quartzite of the Pre-loess Terraces. Other metamorphic rock types such as metamorphic quartz clasts and quartzite are more abundant when compared to the Pre-loess Terraces. Varieties of micaceous slate and phyllite, along with dark greenstone are abundant in Mississippi River gravels but are absent from the Pre-loess Terrace gravels. Slate and phyllite varieties range in colors of green, red, brown, and grey.

Piedmont Quartz

Metamorphic quartz and vein quartz gravel clasts can be found along stream valleys that drain the Cretaceous outcrop belt in northeast Mississippi. These gravels represent a Pleistocene residuum from larger rivers that once drained across the Black Prairie Region long ago with headwaters in the southern Piedmont of the Appalachian Mountains. Piedmont Quartz gravel is white to pink, often grainy, pebble to cobble size, with the larger clasts dominantly being metamorphic quartz. They increased frequency and size south and east along the Cretaceous outcrop belt. The large clasts of metamorphic quartz made excellent hammerstone material and the vein quartz (milky quartz) component was commonly utilized for projectile points in the absence of locally available chert gravels.

References: The Upper Cretaceous Deposits of Mississippi Bulletin

Clay Resources

Clays are abundant throughout Mississippi, but the availability of ceramic-quality, kaolinitic clay resources are much more nuanced. Clay foom unweathered bedrock formation sources is generally unsuitable for ceramic manufacturing because they lack the proper kaolin mineralogy for the properties of successful firing. The adverse higher shrink and swell potential for non-kaolinitic clays may also prove unsuitable for non-ceramic purposes, like daub. Some occurrences of deeply weathered bedrock clays that have reverted to kaolin do exist and are exceptionally suited for ceramics. This occurs most notably in the Graham Ferry Formation, clays of the Wilcox Group, and outcrops of more terrestrial facies of the Cook Mountain Formation. Kaolinic clay resources for ceramics were typically utilized from clay in the alluvium of streams and rivers. These resources also have a natural temper of silt, sand, and organic impurities. Certain general geologic source inferences may be ascertained by studying the natural impurities in ceramics such as loess, mica, or heavy minerals.

References: Clays of Mississippi Bulletin; Pottery Clays of Mississippi Bulletin

Loess Dolls

Loess is an aeolian silt deposit that unconformably blankets the eastern valley wall of the Mississippi River. It has substantial local variation in thickness and lateral extent to the east. Loess is typically calcareous with dolomite and calcite. Loess contains secondary deposits of calcareous concretions referred to as loess dolls or loess kindchen. Loess dolls vary highly in shape and size and can be earthy to limestone-like. Loess dolls were utilized for carved objects such as plummets and pipes.

References: Loess Investigations in Mississippi Bulletin

Bauxite

Bauxite is not a true mineral, but a type of laterite composed of hydrated alumina with variable constituents of iron oxides and hydroxides, along with manganese. It is brick-red in color with yellow-to black and brown mottles. Bauxites in Mississippi range in consistency from a loose, soft clayey aggregate of concretionary pellets to a chert-like hard, competent stone. Bauxite’s distinctive texture is referred to as pisolitic. The workability and unique appearance of the stone made it an ideal trade item for the manufacturing of beads and other ground ornaments. Much of the bauxite in archaeological context in Mississippi is attributed to outcrop sources in Arkansas, though high-quality bauxite does indeed occur naturally in Mississippi. The most notable occurrences are in northeast Mississippi. It forms as a residuum along the Paleocene outcrop belt of the Porters Creek Formation clays in Tippah County. Mississippi’s bauxite resources were also likely exploited by Native American cultures in the archeological past.

References: Bauxite Deposits of Mississippi

Authors: Starnes, J., Segrest, B., and Leard, J.

Published: May 2019

Updated: Dec 2023

A significant update to verbage was implemented June 2023.

Cockfield Quartzite Pictures were added Dec 2023.